The Galloping Ghost (34 page)

Read The Galloping Ghost Online

Authors: Carl P. LaVO

Gene waves goodbye to residents of Nam Kwan and departs on the Chinese junk that carried him into the harbor.

Courtesy Fluckey family

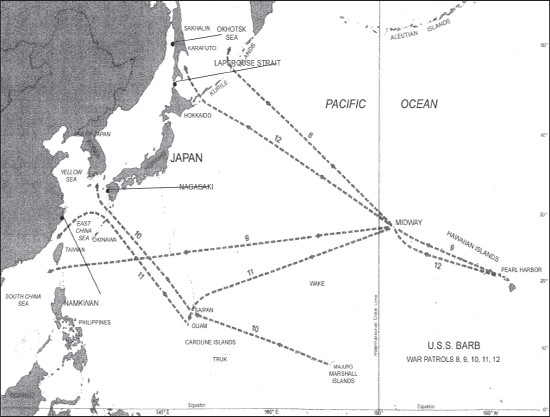

The routes of the USS

Barb

's five war patrols under the command of Gene Fluckey, 1944-45.

Genevieve LaVO

Nationalism was sweeping Africa, toppling colonies ruled for two centuries by Britain, France, Belgium, Portugal, and Spain. Rioting had erupted in British Nyasaland and the Belgium Congo, leading to independence and more rioting. Republics had been proclaimed in Central Africa, Niger, Upper Volta, Ivory Coast, and Dahoney. In South Africa the English-speaking white government clung to power amid international condemnation and internal unrest over its institutional racism. The United States viewed the continent as ripe for communist expansion at a time when newly elected President John F. Kennedy grappled with a series of foreign policy setbacks. Within days of Solant Amity II's departure from Norfolk, two huge public relations disasters faced the president. On 12 April the Russians won the race to place the first man in orbit around the earth. Five days later a small force of rebels supported by the CIA landed at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba in an attempt to overthrow the communist government of Fidel Castro. Soviet-armed troops backed by tanks crushed the invaders. Kennedy accepted full responsibility for the failed plot to a howl of worldwide scorn. The fledgling president was in need of any bit of good newsâthe kind vested in Gene Fluckey.

Coming off the euphoria of the stadium drive in 1958, he had moved quickly toward flag rank by attending the National War College at Fort McNair in Washington followed by a year-long assignment to the National Security Council. On Fluckey's selection as rear admiral in July 1960, Arleigh Burke sent congratulations but warned of how all-consuming his new duties would be: “Being a Flag Officer is much more difficult than anyone anticipates until he is faced with it. Your successes and failures will become well known quickly to many persons both inside and outside the Navy. Your responsibilities will increase tremendously and examples you set will have much greater effect than you as an individual perhaps realize now.”

Fluckey's first assignment was command of Amphibious Group 4, the so-called Brush Fire Brigade that guarded American interests in the Caribbean. The rear admiral learned to scuba dive and practiced undersea demolition techniques with his commandos. In January 1961 he had operational tactical command of a naval Task Fleet comprising sixty-five ships off the tip of Puerto Rico during a naval parade for forty-seven generals and admirals from Central and South America.

Returning to Norfolk after months at sea, Gene was hopeful of a little shore duty that might extend into the summer. If that wasn't possible, he and Marjorie anticipated the amphibious group being shifted to the Mediterranean, where she could relocate to an overseas base, allowing her to be with her husband at least some of the time.

But that was not to be.

Â

The Solant Amity II mission was part of a broad initiative by the Kennedy administration to collect intelligence and curry influence in Africa south of the Sahara. An earlier voyageâSolant Amity Iâhad visited South America and the west coast of Africa between November 1960 and May 1961. Fluckey's objective as commander of Solant Amity II was to venture to the turbulent east coast of the continent to establish friendships with new governments.

The task force of Solant Amity II consisted of the amphibious dock landing ship USS

Spiegel Grove

(LSD-32), a tank landing ship, two destroyers, and a small refueling tanker. The ships carried 1,670 officers and men, including a company of 450 Marines and 6 helicopters aboard

Spiegel Grove,

Fluckey's flagship. The idea was to host dignitaries in each country visited, open the ships to tours to show off the Navy's equipment and personnel, participate in parades, stage performances by task force musicians, and distribute supplies and gifts. It took almost six weeks to fill the holds of the ships with food, candy, sporting equipment, souvenirs, toys, magazines, packets of seeds, Polaroid cameras, and fourteen tons of medical supplies.

Fluckey had hoped to make it an all-inclusive visit to Africa, including stopovers in Portuguese territories. But the Navy declined. “Everyone turns down my request to visit the Portuguese Colonies to avoid widening the U.N. breach [with Portuguese colonial policies] which I argue endangers our primary foreign policy of maintaining NATO intactâand the Portuguese commanding there now are old friends from Lisbon,” Fluckey groused in a letter to retired Admiral Nimitz. The Navy, however, was in a dilemma. Portugal, one of the founding members of NATO and staunchly anticommunist, was determined to hang on to its African colonies. Resulting bloody clashes between Portuguese soldiers and African rebels had cost numerous lives on both sides.

With visits to the Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique off limits, Fluckey set to the task of popping in and out of ports around the horn of Africa and up the east coast. From 1 May to 1 September Solant Amity II visited nineteen African countries and twenty-eight ports-of-call. The commander frequently went ashore to visit dignitaries or made helicopter visits to remote villages. He was a natural with his cheery disposition and willingness to engage people everywhere, young and old. He was a striking visage alighting from his helicopter in a short-sleeved, tropical white uniform in the remote deep bush village of Tsevie in Togo to present

athletic equipment, candy, and medical supplies to tribal chiefs. In the former French colony of Gabon in west-central Africa, he did the same thing, winging into Lambarene in helicopters loaded with two thousand pounds of medical supplies for Dr. Albert Schweitzer. The Nobel Peace Prize-winning physician and humanitarian lunched with the rear admiral and escorted him around his hospital and the village for 4 hours, posing for photographers and discussing conditions in Gabon. Schweitzer was concerned independence had come too soon for a society not prepared to govern itself. “[Schweitzer] reminded me of Fleet Admiral Nimitzâthat twinkle in his eye and the soul-pervading humility. What a man!” Fluckey later recalled.

In the South African port of Durban, South Africa's “Lady in White” serenaded Solant Amity II on its arrival. Throughout World War II, as troopships embarked from Durban to support the British, soprano Perla Sidle Gibson would appear on the North Pier with a megaphone to sing patriotic and farewell tunes that the sailors could hear as they passed. She never wavered from a vow to see off every single troop carrier. Now, as Solant Amity II prepared to depart, she stood dressed in her symbolic white dress on North Pier to give Rear Admiral Fluckey a ceremonial kiss before he climbed aboard his flagship. “She was warbling âGod Bless America' as she had done on our arrival,” wrote Gene in a letter home. “Thousands lined the decks all the way out to the end of the jetty and I counted 39 persons who waded out on the mud flats, fully clothed, waving goodbye to us and singing with the band, âAuld Lang Syne.' What a parting! It's enough to make Admirals weep.”

In French-speaking Madagascar the rear admiral attended a ceremony in which live game was fed to sacred crocodiles, supposedly descended from humans. He also visited Catholic and Protestant churches and a mosque, where he joined five hundred barefooted Muslims. He took off his shoes and stood in his socks on the dirt floor. The iman gave a twenty-minute speech. “It made it necessary for me to respond with a ten-minute impromptu speech in French; they were so thrilled by my French speech that the Iman requested my permission to say a prayer in my behalf, and 500 voices droned away for me and cleansed me of all my sins past, present, and future; then when I thanked them for this soul stirring prayer they became so happy they chanted a prayer for all my ships; late that evening I washed my dirty socks which I fear will never come clean.”

In Madagascar Fluckey stood before the press, which threw him a curve. “If you have an Amity visit to a colored Republic such as this, don't you think you should have one to your own colored people in Alabama who

are being beaten?” asked one reporter, referring to civil rights demonstrations in the United States. The admiral answered with grace and humility. As he recalled, “I think they were a bit surprised when I admitted we weren't perfect, that great progress had been made, that we have a great American dream of equality which we believe can be achieved, that 95 percent of our schools are integrated, and that we have over two hundred thousand Negroes in our colleges and universities.”

The task force moved on to the Seychelles, a British dependency of ninety largely uninhabited islands scattered across the western Indian Ocean north of Madagascar. Solant Amity II anchored at Port Victoria on Mahe Island, which Fluckey termed “a nice sleepy port set in the Garden of Eden.” The republic was governed by Sir John and Lady Thorp, who hosted a state banquet in their Victorian mansion. “Pancahs swinging back and forth over the table provided the equivalent of air conditioning,” Fluckey later noted. “A pancah is a heavy drapery about ten feet wide and four feet in depth attached to a yardarm rigged athwart the table and well above it. Through a system of rigging, the three pancahs spaced over the table are joined by a single rope that runs out through a hole in the wall, over a pulley, and down into a section of the kitchen, where a servant sits tugging on the rope to set the pancahs swinging back and forth. The resultant breeze is delightful.”

The following morning Lady Thorp taught the rear admiral how to surfboard at the couple's beach residence, then had him join her in snorkeling over nearby reefs. “It's the most beautiful skin-diving in all the worldâa myriad of unbelievably-colored fish that make all aquariums appear drab,” he wrote Marjorie. He described a return visit at daybreak. “At that time the fish are so dormant one can bring his finger tips within an inch of the fish, attempting to caress them before they lazily move away. As the sun bursts over the low mountains the underwater world breathtakingly changes from subdued light grey hues to a kaleidoscope of sparkling, animated, crisscrossing rainbows.”

From Port Victoria the task force steamed to French-speaking Reunion Island, then to Zanzibar for refugee relief, and on to Mombassa and Aden, before returning to Cape town in South Africa. It was there that Fluckey received orders to fly across Africa to Liberia to be the U.S. naval representative for the 114th Independence Day Celebrations. The Navy had diverted the USS

Valcour

to Monrovia to be Fluckey's flagship during his stay.

Among the many events he attended was an all-night ball. “Did I get integrated!” reported Fluckey in a letter home.

Never having danced with an African before, my destiny as the only Caucasian at the President's table was obvious. Kindly they offered to get me a good-looking African partner, but being a bit dubious even of Caucasian blind dates, I assured them that I preferred to dance with their lovely wives. Having thrown the gauntlet down, I quickly looked around the table for the best looking target for my first experience, and settled on the Attorney General's wife. They were all beautifully gowned and she was most attractive. Yet when I nervously held her in my arms, I could feel my scalp starting to perspire from the crown of my head down. She remarked that it was very warm and perhaps it would be cooler if we danced around the edge of the floor. After a while it was like putting your feet in hot water, once in it's nice and comfortable and the perspiration stopped. I must say these Africans have a built-in rhythm.

The next dance was a âHigh Life'âthis is very popular on the East Coast of Africa. It's sort of a cross between a shuffle, rock and roll, the mamba and the bunny hop. This time I reached higher and asked the Vice President's wife to dance. Unbeknownst to me she is known as being a good strong dancer. She whisked me around the floor like a graceful camel with me doing something akin to a hula while I swear she was doing an Egyptian belly dance. I just couldn't do the forward and backward grinds and keep in time with the music. All I could think of was “if they would just take a movie and send it back to Admiral Burke, he'd recall me from Africa post-haste.” . . . During the night I danced with all their wives, all of whom were charming, delightful people. Consequently my thinking and philosophy have changed considerably. Having had my eyes opened, I am led to believe that Americans, on the whole, are the biggest racial snobs in the entire world.

Generally events were well organized and went off without incident. But occasionally a problem developed, sometimes with humorous consequences.

In the former French colony of Dahomey, the admiral hosted a dinner aboard

Spiegel Grove

for the nation's first president, Herbert Maga. An enormous man, he came alongside the ship in the admiral's barge and, in heaving seas, almost lost his balance twice and nearly toppled into the sea. Two seaman were able to get a firm hold and finally heave him up a ladder to the ship's deck. As he was piped aboard, another big roller caused him to lose his balance and knock over the officer of the deck and several seamen like bowling pins. Recovering his dignity, Maga went below, where Fluckey apologized.