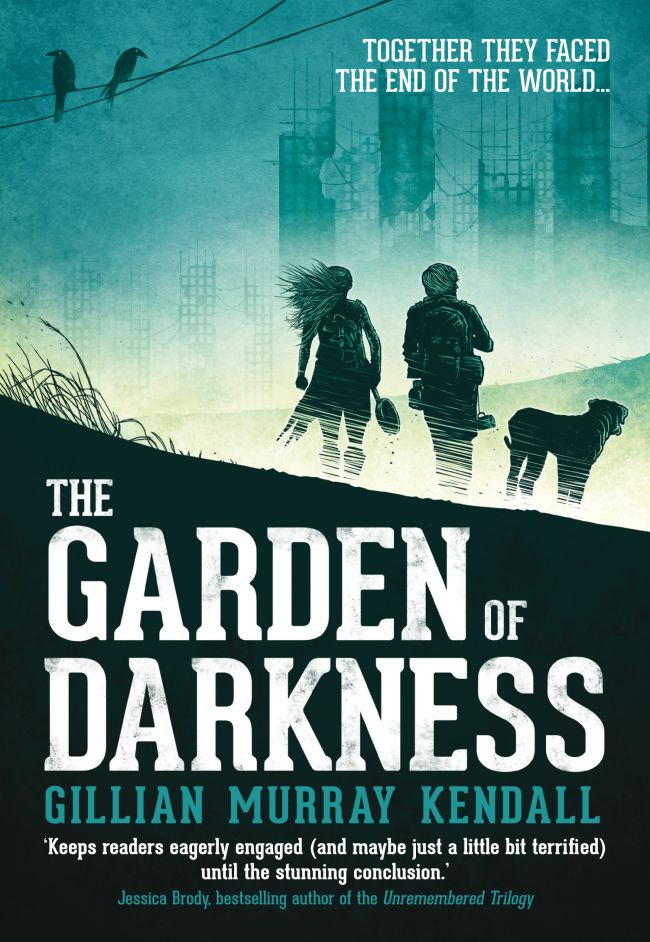

The Garden of Darkness

First published 2014 by Ravenstone

an imprint of Rebellion Publishing Ltd,

Riverside House, Osney Mead,

Oxford, OX2 0ES, UK

ISBN: 978-1-84997-762-3

Copyright 2014 Gillian Murray Kendall

Cover art by Luke Preece

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners.

Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night;

Nor for the arrow that flieth by day;

Nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness.

Psalm 91

For Rob

and for Sasha and Gabriel (of course)

After They Left the City

T

HE PANDEMIC BURNED

through the population until only a few children remained. The adults died quickly. When SitkaAZ13, which everyone called Pest, first began to bloom, Clare and her father and stepmother, Marie, listened to the experts on the television—those desperately mortal scientists with multiple initials behind their names. And then one by one the experts had dropped away, taken by the pandemic they so eagerly described.

But not before they’d made it clear: while a very few children might prove resistant to the disease until they reached late adolescence, all of the adults were going to die. All of them.

Clare had found it hard to watch her father and Marie, still vital, still healthy, and know that the two of them would soon be dead. She supposed she would be dead too before long. The odds weren’t great that she would prove to be one of the few who lived into their late adolescence. Her father and Marie simply tried not to talk about death. Not until her father’s words at the very end.

N

OW IT WAS

over, and Clare, a temporary survivor after all, stood on Sander’s Hill looking down at the giant necropolis that stretched out below her—the city of the dead and dying. The city of crows.

Clare was fifteen years old. And it astonished her that she was still alive. Everything that told her who she was—the intricate web of friendships and family that had cradled her—was gone. She could be anyone.

CHAPTER ONE

SCENES FROM A PANDEMIC

C

LARE AND HER

father and stepmother survived long enough to leave the dying city in their neighbor’s small Toyota. The family SUV was too clunky and hard to maneuver, and their neighbor, decaying in his bed, offered no objections when they took his more fuel-efficient car. Their departure was hurried and late in the day—they had spent most of the day waiting for Clare’s best friend, Robin, to join them. But Robin never came. They daren’t stay any longer; the Cured now ruled the city at night.

Clare knew that once they left the city, there was no possibility she would ever see Robin again. While Clare had loved Michael, still loved Michael, would always love Michael, her friendship with Robin was inviolate. Which was why Clare knew that if Robin could have made the rendezvous, she would have. They might wait a thousand years, but Robin would not come. Clare did not doubt that someone—or something—had gotten her.

On that fresh summer day, as the shadows began to creep out from under the trees, and the strange hooting of the Cured began to fill the night, Clare was under the illusion that she had nothing more to lose. She had, after all, even lost herself—she had been a cheerleader; she had been popular; she had been a nice person. And under that exterior was something more convoluted and complicated, something that made her wakeful and watchful, that made her devour books as the house slept. But none of that mattered anymore. Her cheerleading skills were not needed. And there was nothing to be wakeful about anyway: the monster under the bed had been Pest all along.

T

HEY WERE TAKING

all the supplies they could fit into the car, but they were not taking Clare’s parakeet, Chupi. Marie talked about freeing the bird, but Clare knew that Chupi would not last a winter. She knew that Marie knew it, too. When it was almost time to go, Clare got into the Toyota listlessly, fitting her body around backpacks and cartons of food and loads of bedding and enough bandages and bottles of antibiotics to stock a small pharmacy.

Then she got out again. Her father and Marie were arguing heatedly about who was going to drive as she slipped into the house. “No, Paul,” Marie said in her patented Marie-tone, “

I’m

a better driver on the freeway.”

Clare went straight to Chupi’s cage. They had never had a cat or a dog. Marie was allergic to both. That left fish or something avian. It was a choice that wasn’t a choice—Clare wasn’t about to bond with a guppy or deal with ick—so they bought her a birthday parakeet. And, eventually, Clare found that Chupi charmed her. The parakeet would hop around Clare’s books while she studied. Occasionally, he would stop and peck at the margins of the pages until they were an amalgam of little holes, as if Chupi had mapped out an elaborate, unbreakable code in Braille.

Chupi’s release was to come right before they left. Her father, Paul, didn’t have the heart to wring the bird’s neck—Clare knew that Chupi had charmed him, too. Marie’s delicate sensibilities made her a non-starter for the task, although Clare thought that, actually, Marie might turn out to be rather good at neck-wringing. They didn’t ask Clare.

When Clare got to Chupi’s cage, she opened the door and pressed gently on the parakeet’s feet so that he would pick up first one foot and then the other until he was perched on her finger. Then she transferred him to a smaller cage. The car was packed tightly, but there was a Robin-size gap in it now, and she had suddenly determined that Chupi, with his bright blue wings and white throat, was coming with her. He was going to be all she had of the old world.

She returned to the car. The argument between Marie and her father had apparently been settled, and her father said nothing when he saw Clare and Chupi. When Marie opened her mouth in protest, he said, “Never mind.”

Clare leaned forward to wedge the cage next to a sleeping bag. She wore a low-cut T-shirt and Michael’s Varsity jacket, unsnapped, and she looked down for a moment at the pink speckles sprinkled across her chest: the Pest rash. It was like a pointillist tattoo done in red. They all had the Pest rash, but so far they hadn’t become ill.

As they began the drive, her father and stepmother scanned the roads for wreckage. Marie had a tire iron in her hand.

“What’s that for?” asked Clare.

“Just in case,” said Marie.

Clare tried and failed to picture Marie wielding a tire iron against one of the Cured. Marie was a runner.

They were retreating to their house in the rolling countryside.

They drove until they came to a place where the highway was blocked by four cars and a tractor-trailer. When her father left the car to explore the collision, Clare was sure he wouldn’t return.

“Be careful, Paul,” yelled out Marie, alerting all the Cured in the area. Clare pictured hands reaching out of the wreck and pulling him in like something out of a zombie movie; she pictured faces sagging with Pest leering out of the windows.

But he came back to report that the vehicles were empty. There was a basket of clean laundry in one of the cars, and they rummaged through it and took a blanket from the bottom of the hamper. He had found some pills in the glove compartment of the tractor-trailer. He took those, too.

There was no way to maneuver around the wreckage, so they filled their backpacks with as much food as they could carry and left the car.

“Once we get clear of this mess,” said her father, “we’ll look for another car.”

“I didn’t know you could hot-wire cars,” said Clare, impressed.

“We’re going to look for a car with keys in the ignition.”

“Oh.” Clare poked holes in a shoebox and, after putting Chupi in it, placed him at the top of her pack. She jammed him solidly between a bunch of fresh bananas and a can of baked beans. It was when they started moving on foot that Clare noticed that her father’s face was flushed. She stopped walking, and the cans in her pack pressed against her back as she stared at him. She was suddenly afraid of all that the angry patches on her father’s cheeks and forehead might mean. Then—

“We have to go on,” he said to her. “No matter what.”

They found a car late that afternoon—an abandoned Dodge Avenger with the keys dangling from the ignition.

It took them three long days to get to Fallon. Both Marie and Clare’s father were too tired to drive all night, so they stopped and made camp and engaged in the pretense of sleeping. Two would huddle together under the sleeping bags while the third stood watch. Mostly Clare found herself lying awake back-to-back with Marie while her father sat against a tree and stared into the dark. She wondered if the sour damp smell she detected were coming from Marie or from her. She knew that smell. It was fear.