The German War (37 page)

Authors: Nicholas Stargardt

Jews crossing from one part of the Łód

ghetto to another.

ghetto to another.

ghetto to another.

ghetto to another.

‘Repatriation’: ethnic Germans from Romania boarding a Danube steamer.

INTIMACIES

Café in Cracow.

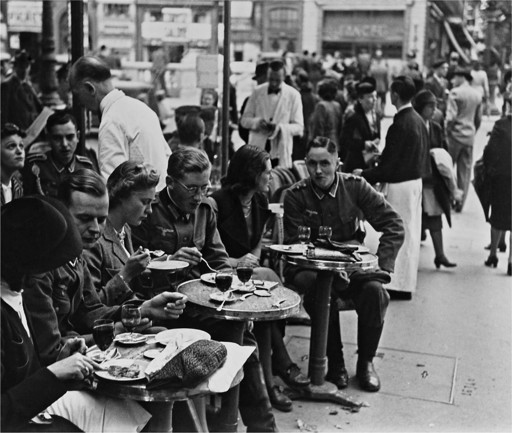

Café in Paris.

German soldiers visit a synagogue converted into a brothel in Brest, France.

Enforcing racial separation at home: a German woman and her Polish lover tied to a pillory in Eisenach, 15 November 1940.

AMONG COMRADES

Fritz Probst (extreme right), Christmas 1939.

Kurt Orgel (second from right), January 1945.

*

On 17 February 1942, Corporal Anton Brandhuber slipped away from his battalion at Aleksandrovka, while it was being marched towards the German front line. A veteran of the campaigns of 1939 and 1940, Brandhuber had found himself amongst hastily despatched replacements from Lower Austria, in which raw recruits rubbed shoulders with experienced soldiers like himself. Their train took them as far as Orel. From there, they marched for three days through –40°C degree blizzards. Periodically bombed by the Red Air Force, the men had been kept moving by their pistol-toting officers. They were on their way to shore up the depleted lines of the 45th Infantry Division, the division from Linz which had narrowly escaped the encirclement of the 2nd Army in December. Scanning the faces of the troops they met returning from the front to see what awaited him, Brandhuber saw only ‘drained, over-tired and distrustful and miserable’ men. At halts, they spoke of their winter retreat and of the enormous amounts of equipment they had had to abandon.

20

20

Perhaps his experience of the campaigns against Poland and France had given Anton Brandhuber a heightened sense of present danger. He set off from Aleksandrovka alone, and when he had walked back 15 kilometres along the road they had come, he buried his rifle along with his gas mask and cartridge case under the snow and ate his bread. Still in his uniform, but now without most of his equipment, Brandhuber managed to hitch a ride from a passing car to the next railway junction, where he made his way to sidings. Mingling with the lightly wounded, he climbed on to a train which took him via Orel to Gomel, and then through Bryansk to Minsk. At Orel, a Russian woman took him in but for most of the time, Brandhuber slept in station waiting rooms, stealing bread from army bakeries.

The German military police regularly patrolled railway stations on the lookout for deserters, and travelling further west Corporal Brandhuber was picked up by German patrols twice, at Brest Litovsk and Warsaw. Each time the officers were persuaded that this campaign-hardened and dependable-looking non-commissioned officer had simply been separated from his unit, despite his conspicuous lack of equipment. Instead of arresting him, they bawled at him to proceed back to Orel and rejoin the 45th Infantry Division as quickly as possible. Once they were safely out of sight, Brandhuber continued westwards. At Brest, he paid an engine driver with two packets of tobacco to ride in his cab all the way to Warsaw. There, after narrowly avoiding arrest for the second time, he spotted in the sidings a passenger train bound for Vienna, which he took as far as Bludenz and Buchs. He crossed the Swiss border on 27 February, exactly ten days, 3,000 kilometres and 3 kilos of bread after he absconded at Aleksandrovka.

Anton Brandhuber was both an experienced soldier and the most unmilitary of men. He explained his motives to the Swiss military officers who interrogated him with a laconic brevity worthy of the good soldier Schweik: ‘It just seemed too stupid to me.’ He did not want to make a career in the Wehrmacht; and in early 1942 he was worried about how he would fare in the event of a German victory. He was not interested in becoming the administrator of a large collective farm in Russia, and he did not want to serve in an army of occupation. Nor had he developed any strong attachment to his comrades. He just wanted his old life back, on the family farm in Laa an der Thaya in Lower Austria, with its three horses, seven cows, a dozen pigs and 8 hectares of land. That was where he had grown up and where the 87-year-old Brandhuber was still to be found in the summer of 2001, as self-contained and unforthcoming as ever. He had nothing to add to the explanation he had given the Swiss military for his desertion fifty-nine years before, telling the young German historian who came to interview him in almost identical terms: ‘I didn’t fancy it any more.’

21

21

Military pronouncements and Nazi propaganda emphasised again and again that deserters were traitors and cowards, men who abandoned and imperilled their comrades and who selfishly and cunningly undermined their efforts to hold the line. What was so remarkable about Anton Brandhuber was that he did not try to repudiate these accusations. On the contrary, he acknowledged that he fled precisely because he did not want to be a soldier and because he did not like what he saw on the eastern front in February 1942. Like others, he was dismayed by the brutality of this German war, by the devastation of the Belorussian and Russian towns and countryside and by the killing of Jews – which he had witnessed at close hand on his way through Orel. Other German deserters told stories to their Swiss interrogators which justified their flight as a response to earlier run-ins with military authority or to being mistakenly sent to court martial for things they had not done, and virtually all of them went to great lengths to repudiate the implication that deserters were selfish cowards by stressing their military records of heroic devotion to their comrades. Brandhuber stands out because he did none of these things, telling a tale which lacked any trace of the language of Nazism or the German military. Whereas another Catholic farmer’s son like Albert Joos filled the pages of his diary with patriotic duty, comradeship and sacrifice, these powerful emotional appeals did not exercise a hold on Anton Brandhuber. Even amongst the idiosyncratic ranks of German deserters he stands out for being so unaffected by the values of his age.

It was extremely difficult for soldiers to escape from the front line. The proximity of the German and Soviet lines encouraged each side to use megaphones to encourage desertion. By everything from idealistic appeals to international working-class solidarity to promises of decent food, Germans were exhorted to cross the lines. It was dangerous, but not impossible: since small scouting parties went out on regular nightly patrols, men could slip away, hoping to be brought in by a raiding party from the other side. But eyewitness accounts of finding the mutilated corpses of German soldiers who had tried to surrender were told and retold within German units, acting as a serious deterrent and, in turn, legitimising further killings of Soviet prisoners. The only real prospect of successful flight lay in the German rear, but it was extremely difficult to travel along the roads and railway lines westwards, find shelter and food, without being detected. Perhaps because so few men attempted to do so, the military police patrols who stopped Brandhuber at Brest and Warsaw were inclined to believe that he had been accidentally separated from his unit.

22

22

Other books

Psycho Within Us (The Psycho Series Book 2) by Chad Huskins

Koyasan by Darren Shan

The Second Lady Southvale by SANDRA HEATH

Waiting for Him by Natalie Dae

With Good Behavior by Jennifer Lane

Blurred Boundaries by Lori Crawford

Love 2.0 by Barbara L. Fredrickson

Deviations by Mike Markel

You or Someone Like You by Chandler Burr

Fostering Love (The Soul Sisters Series Book 1) by Johns, Victoria