The Gifts of the Jews: How a Tribe of Desert Nomads Changed the Way Everyone Thinks and Feels (2 page)

Authors: Thomas Cahill

But if we make use of what hints remain in the prehistorical and protohistorical “record,” we must come to the unexpected conclusion that their inventions and discoveries, made in aid of their survival and prosperity—tools and fire, then agriculture and beasts of burden, then irrigation and the wheel—did not seem to them innovations. These were gifts from beyond the world, somehow part of the Eternal. All evidence points to there having been, in the earliest religious thought, a vision of the cosmos that was profoundly cyclical. The assumptions that early man made about the world were, in all their essentials, little different from the assumptions that later and more sophisticated societies, like Greece and India, would make in a more elaborate manner. As Henri-Charles Puech says of Greek thought in his seminal

Man and Time:

“No event is unique, nothing is enacted but once …; every event has been enacted, is enacted, and will be enacted perpetually; the same individuals have appeared, appear, and will appear at every turn of the circle.”

The Jews were the first people to break out of this circle, to find a new way of thinking and experiencing, a new way of understanding and feeling the world, so much so that it may be said with some justice that theirs is the only new idea that human beings have ever had. But their worldview has become so much a part of us that at this point it might as well have been written into our cells as a genetic code. We

find it so impossible to shed—even for a brief experiment—that it is now the cosmic vision of all

other

peoples that appears to us exotic and strange.

The Bible is the record

par excellence

of the Jewish religious experience, an experience that remains fresh and even shocking when it is read against the myths of other ancient literatures. The word

bible

comes from the Greek plural form

biblia

, meaning “books.” And though the Bible is rightly considered

the

book of the Western world—its foundation document—it is actually a collection of books, a various library written almost entirely in

Hebrew over the course of a thousand years.

We have scant evidence concerning the early

development of Hebrew, one of a score of Semitic tongues that arose in the Middle East during a period that began sometime before the start of the second millennium

B.C.

1

—how long before we do not know. Some of these tongues, such as Akkadian, found literary expression fairly early, but there is no reliable record of written Hebrew before the tenth century

B.C.

—that is, till well after the resettlement of the Israelites in Canaan following their escape from Egypt under the leadership of Moses, the greatest of all proto-Jewish figures. This means that the supposedly historical stories of at least the first books of the Bible were preserved originally not as written texts but as

oral tradition. So, from the wanderings of Abraham in Canaan through the liberation from Egypt wrought by Moses to the Israelite resettlement of Canaan under Joshua, what we are reading are oral tales, collected and edited for the first (but not the last) time in the tenth century during and after the kingship of David. But the full collection of texts that make up the Bible (short of the Greek

New Testament, which would not be appended till the first century of our era) did not exist in its current form till well after the Babylonian Captivity of the Jews—that is, till sometime after 538

B.C.

The last books to be taken into the canon of the Hebrew Bible probably belong to the third and second centuries

B.C.

, these being Esther and Ecclesiastes (third century) and Daniel (second century). Some apocryphal books, such as Judith and the Wisdom of Solomon, are as late as the first century.

To most readers today, the Bible is a confusing hodgepodge; and those who take up the daunting task of reading it from cover to cover seldom maintain their resolve beyond a book or two. Though the Bible is full of literature’s two great themes, love and death (as well as its exciting caricatures, sex and violence), it is also full of tedious ritual prescriptions and interminable battles. More than anything, because the Bible is the product of so many hands over so many ages, it is full of confusion for the modern reader who attempts to decode what it might be about.

But to understand ourselves—and the identity we carry so effortlessly that most “moderns” no longer give any thought to the origins of attitudes we have come to take as

natural and self-evident—we must return to this great document, the cornerstone of Western civilization. My purpose is not to write an introduction to the Bible, still less to Judaism, but to discover in this unique culture of the Word some essential thread that runs through it, to uncover in outline the sensibility that undergirds the whole structure, and to identify the still-living sources of our Western heritage for contemporary readers, whatever color of the belief-unbelief spectrum they may inhabit.

To appreciate the Bible properly, we cannot begin with it. All definitions must limit or set boundaries, must show what the thing-to-be-defined is not. So we begin before the Bible, before the Jews, before Abraham—in the time when reality seemed to be a great circle, closed and predictable in its revolutions. We return to the world of the Wheel.

1

Recently, the designations

B.C.E.

(before the common era) and

C.E.

(common era), used originally in Jewish circles to avoid the Christian references contained in the designations

B.C.

(before Christ) and

A.D.

(

anno domini

, in the year of the Lord), have gained somewhat wider currency I use

B.C.

and

A.D.

not to cause offense to anyone but because the new designations, still largely unrecognized outside scholarly circles, can unnecessarily disorient the common reader.

T

HE

T

EMPLE IN THE

M

OONLIGHT

The Primeval Religious Experience

The Primeval Religious ExperienceS

omewhat more than five millennia ago, a human hand first carved a written word, and so initiated history, mankind’s recorded story. This happened in Sumer, probably in a warehouse of Uruk, perhaps the earliest human habitation to deserve the name of “city,” massed along the Euphrates River in ancient Mesopotamia—modern Warka in present-day Iraq. The written word was an invention born of necessity: how else were the Sumerians to keep their accounts straight? The novel agglomeration of human beings and their possessions into a city such as Uruk—a mind-defeating jumble of temples, dwellings, storerooms, and alleyways, an agglomeration soon to be imitated throughout the ancient world—cried out for a new way of counting shipments and recalling transactions, for a man’s memory was no longer sufficient to encompass such immensities. The human mind wearied before the task, growing resistant and uncooperative—and, at last, alarmingly error-prone—but human ingenuity proposed a damnably clever solution: enduring written symbols to replace fallible human memory.

This innovation, which would change forever the course of the human story, making possible fantastic feats of information storage and retrieval and wholly new forms of communication, both interpersonal and corporate, had been prepared for by other innovations that had preceded it over the long centuries of the Sumerians’ trial-and-error ascent to urbanization. The invention of agriculture—the discovery

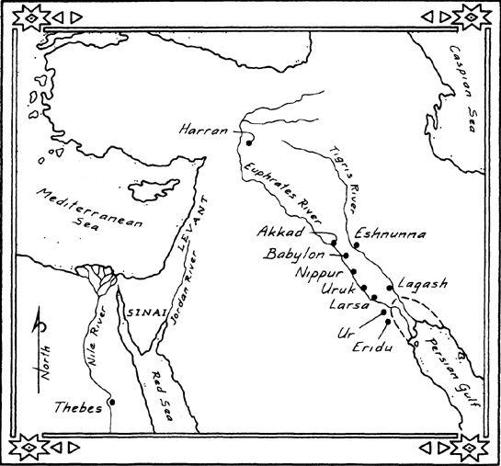

that one need not wait upon the bounty of nature but can organize that bounty more or less predictably through the seasonal planting of seed—had greatly lessened man’s reliance on the uncertain harvests of hunting and gathering and had made possible the first settled communities, organized around a dependable grain supply. The domestication of flocks and herds for predictable yields of eggs, milk, flesh, leather, and wool soon followed (or may even have occurred earlier). The invention of the hoe and the further invention of the plow—which probably occurred when some lazy but sly farmer thought to tie his hoe to a rope hitched to the horn of an ox, thus giving himself considerably more muscle power through the ox’s strength and enabling him to farm a far larger territory—went a long way toward creating stable farming communities throughout the Fertile Crescent, that great arch of watered land stretching north from the Tigris-Euphrates plain, turning south through the Jordan valley, and ending at the Sinai. Someone’s brilliant idea to dig trenches (and then to fashion canals and reservoirs) so that river water could run controllably from higher embankments to lower fields meant that the farmer no longer had to wait for the uncertain rains of the Middle East but could now farm fields he would once have looked on as useless. This technique, refined to exquisite perfection over many centuries, would at last make possible along the broad steppes of the Tigris-Euphrates plain the

Hanging Gardens of Babylon (Babylonia being the direct successor to Sumer), that stupendous wonder of the world, a detailed description of which became the favorite party piece of ancient tourists, thus enabling them to

bore their friends to death long before the invention of photography.

Then, the period just before the invention of written language saw in Sumer an explosion of technological creativity on a scale that would not be matched till the nineteenth and twentieth centuries of our era. For this period witnessed not only the sudden expansion of farming communities with their growing inventory of agricultural and pastoral innovations, but

wheeled transport, sailing ships,

metallurgy, and wheel-turned, oven-baked

pottery—all appearing, as it were, within weeks of one another. The

Sumerians were the first to hit upon the methods of construction that enable human beings to go beyond the simpler feat of providing comfortable shelter for themselves and to erect vastly impressive, even overwhelming enclosures for business and ritual: monumental stone sculpture, engraving, and inlay, the brick mold, the arch, the vault, and the dome all first came to light under the dazzling Sumerian sun. Cumulatively, this unique series of creations made possible for the first time ecumenical trading and, thence, great concentrations of people and possessions and, particularly, the gigantic storage facilities that would encourage our unknown inventor to dream up writing.

By the time the first word was incised on a small clay tablet (which would for many centuries remain the common medium of record), Sumer had risen to dominate all Mesopotamia and had strong trading links and occasionally even political suzerainty as far away as the Nile valley in northern Africa and the Indus valley in the Far East. To the ever-circling

vultures, who no doubt took a dim view of civilization and its unfortunate paucity of easy victims, Sumer appeared a collection of some twenty-five city-states, remarkably

uniform in culture and organization. But to the human hordes of Amorites—Semitic nomads wandering the mountains and deserts just beyond the pale of Sumer—the tiered and clustered cities, strung out along the green banks of the meandering Euphrates like a giant’s necklace of polished stone, seemed shining things, each surmounted by a wondrous temple and ziggurat dedicated to the city’s god-protector, each city noted for some specialty—all invidious reminders of what the nomads did not possess.

T

HE

F

ERTILE

C

RESCENT IN THE

T

HIRD

M

ILLENNIUM

This most ancient cradle of civilization was a great arc of richly irrigated land stretching from the Persian Gulf northwest across the whole Tigris-Euphrates plain, then southwest along the Levant—Jordan River valley and ending at the Sinai. The principal Sumerian-Akkadian city-states are shown (including Babylon, which belongs to a later period). The broken line indicates the shore of the Gulf in the third millennium

B.C.