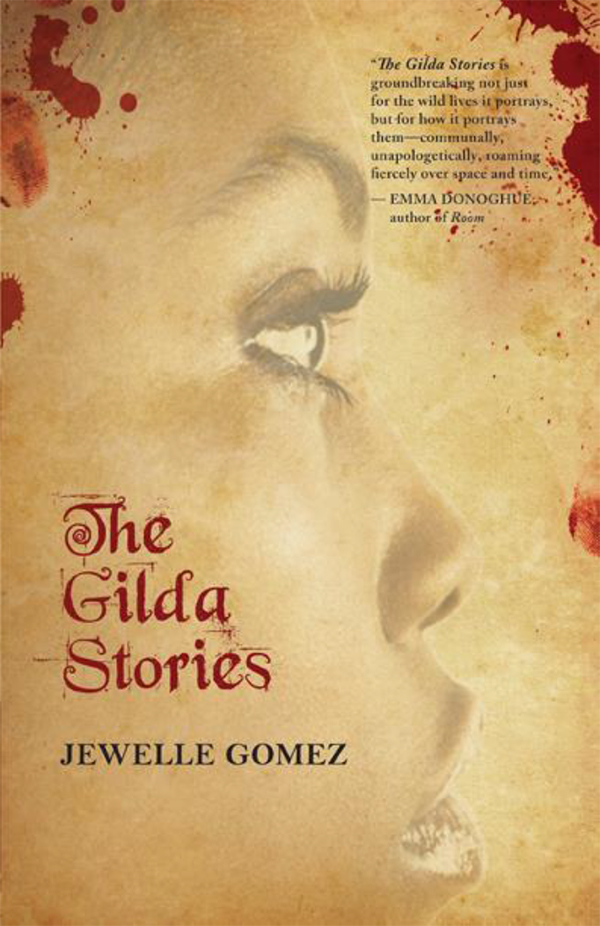

The Gilda Stories

Authors: Jewelle Gomez

“This revolutionary classic by a pioneer in black speculative fiction will delight and inspire generations to come.”

âTananarive Due, author of

Ghost Summer

“The Gilda Stories

is groundbreaking not just for the wild lives it portrays, but for how it portrays themâcommunally, unapologetically, roaming fiercely over space and time.”

âEmma Donoghue, author of

Room

“The Gilda Stories

was ahead of its time when it was first published in 1991, and this anniversary edition reminds us why it's still an important novel. Gomez's characters are rooted in historical reality yet lift seductively out of it, to trouble traditional models of family, identity, and literary genre and imagine for us bold new patterns. A lush, exciting, inspiring read.”

âSarah Waters, author of

Tipping the Velvet

“The Gilda Stories

has been vitally important for the development of a generation of dreamers engaged in radical imagination. It has filled the desires of oppressed and marginalized peoples for stories of the fantastic that wear our faces. It helps so many to understand how to take these mythologies that speak to us, pull them into our flesh, and breathe out visionary communities of resistance.”

âWalidah Imarisha, co-editor of

Octavia's Brood

“Gilda's body knows silk, telepathy, lavender, longing, timeless love, and so much blood. With sensory, action-packed prose and a poet's eye for beauty, Jewelle Gomez gives us an empathy transfusion. This all-American novel of the undead is a life-affirming read.”

âLenelle Moïse, author of

Haiti Glass

“Jewelle Gomez's sense of culture and her grasp of history are as penetrating now as twenty-five years ago, and perhaps more so, given the current challenges to black lives. From âLouisiana 1850' to âLand of Enchantment 2050,' from New Orleans to Macchu Pichu, through endless tides of blood and timeless evocations of place, Gilda's ensemble of players transports me through two hundred years and a second century of black feminist literary practice and prophecy.”

âCheryl Clarke, author of

Living As A Lesbian

“Jewelle Gomez's big-hearted novel pulls old rhythms out of the earth, the beauty shops, and living rooms of black lesbian her-story. Gilda's resilience is a testament to black queer women's love, power, and creativity. Brilliant!”

âJoan Steinau Lester, author of

Black, White, Other

“I devoured this 25th anniversary edition of

The Gilda Stories

with the same hunger as I did when I first read it. I feel a connection to Gildaâher tenacity, her desire for community, her insistence on living among humanity with all its flaws and danger. These stories remain classic and timely.”

âTherà A. Pickens, author of

New Body Politics

“The Gilda Stories

does what vampire stories do best: hold up a larger-than-life mirror in which we can see our hopes, fears, dreams, and flaws. Gilda provides us with a perspective that is too often lost in American history, and a multicultural vision of a better future for us all, human and vampire alike.”

âPam Keesey, author of

Daughters of Darkness

“Jewelle Gomez sees right into the heart. In Gilda's stories she has created a timeless journey, taken us back into history and forward into possibility. This is a book to give to those you want most to find their own strength.”

âDorothy Allison, author of

Bastard Out of Carolina

“In sensuous prose, Jewelle Gomez uses the vampire story as a vehicle for a re-telling of American history in which the disenfranchised finally get their say. Her take on queerness, community, and the vampire legend is as radical and relevant as ever.”

âMichael Nava, author of

The City of Palaces

“With hypnotic prose, Jewelle Gomez shows the immense power of fantasy and the untold stories of American history.”

âCecilia Tan, author of

Black Feathers

Jewelle Gomez

AFTERWORD BY ALEXIS PAULINE GUMBS

City Lights Books | San Francisco

Copyright © 1991, 2016 by Jewelle Gomez

Afterword copyright © 2016 by Alexis Pauline Gumbs

All right reserved

Cover design by em-dash

First published in 1991 by Firebrand Books.

First City Lights edition 2016.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gomez, Jewelle, 1948- author.

Title: The Gilda stones / Jewelle Gomez; afterword by Alexis Pauline Gumbs.

Description: Expanded 25th anniversary edition. | San Francisco : City Lights Publishers, [2016] | “1991

Identifiers: LCCN 2015042172 | ISBN 9780872866744 (softcover) Subjects: LCSH: Lesbian vampiresâFiction. | African AmericansâFiction. | BISAC: FICTION / African American / General. | FICTION / Lesbian. | FICTION / Fantasy / General. | FICTION / Literary. | GSAFD: Horror fiction. | Science fiction. | Fantasy fiction. Classification: LCC PS3557.0457 G5 2016 | DDC 813 /.54âdc23 LC record available at

http://lccn.loc.gov/

2015042172

City Lights Books are published at the City Lights Bookstore

261 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94133

CONTENTS

Chapter Three

Rosebud, Missouri: 1921

Chapter Five

Off-Broadway: 1971

Chapter Six

Down by the Riverside: 1981

Chapter Seven

Hampton Falls, New Hampshire: 2020

Chapter Eight

Land of Enchantment: 2050

Afterword

Blood Relations: Gilda and the Stakes of our Future

A sincere thanks to those who encouraged and assisted me during this long process that has traversed many lifetimes: Cheryl Clarke, Dorothy Allison, Elly Bulkin, Marianne Brown, Sandra Lara, Leslie Kahn, Alexis DeVeaux, Evelynn Hammonds, Audre Lorde, Gregory Kolovakos, Michael Albano, Katie Roberts, Barbara Smith, Nancy Musgrave, Lucy Loyd, Jonathan Leiter, Robin Hirsch, Marilyn Hacker, Maria Lachina, Eric Garber, Arlene Wysong, Morgan Freeman, Gloria Stein, Eric Ashworth, Zuri McKie, Marty Pottenger, Linda Nelson, Laurie Liss, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Michele Karlsberg, Amy Scholder, Elaine Katzenberger, Stacey Lewis. My family in Pawtucket, at 146 West Newton Street and the SFPL. The Beard's Fund, the Barbara Deming/Money for Women Fund and the Lambda Literary Foundation. And Diane Sabin.

As always my work is dedicated Gracias Archelina Sportsman Morandus, Lydia Mae Morandus, Dolores Mae Minor LeClaire, and Duke Gomes.

At night sleep locks me into an echoless coffin

sometimes at noon I dream

there is nothing to fearâ¦.

Audre Lorde

One summer evening BC (before cell phones), my home telephone was out of order so I strolled down to the corner in the musky urban night air of Manhattan to call a friend from a phone booth. As I was talking two male passersby started telling me in lewd detail what sex acts they would like to perform on me. I thought about the fact that women go through this debasement regularly, routinely. How we usually steel ourselves and block it out. But this time, on that evening long ago, rage welled up in me like a tidal wave. I told my friend on the other end of the line to hold on.

I turned on the two men and began screaming like a mythical banshee. I could see that they thought I was overreactingâthey were “just being guys.” But my harangue exploded uncontrollably, stripping away their macho posturing. One man yelled desperately to the other, “Brother, she's crazy!” He clutched at his friend's arm and they fled down the street away from me. I was shaking with the pent-up fury of all the women who've ever been harassed on the street. I came back to myself when I heard my friend, terrified that I was being murdered, shouting my name through the telephone receiver. I thought with shock that if I had had a weapon in hand I would have gleefully beaten or shot or stabbed or bombed those two guys. Instead I went back to my flat and wrote the first installment of what would become

The Gilda Stories.

In Gilda, I created a character who escapes from her deep sense of helplessness as a slave and gains the ultimate power over life and death. She becomes a witness over time to the injustices that humans visit upon one other. Alone on the road she is ill-equipped to protect herself from the brutal and predatory paddy roller who would return her to slavery. The trauma of the escape and the violence that surrounds her path to freedom is a weight she must bear through time. Each new decade brings reminders that the culture has not yet healed the wounds left from slavery and bigotry. Gilda must learn to leave those she loves behind without bending under the further weight of loneliness. Throughout her journey she tries to hold on to her humanity and help others to find theirs.

There were those who didn't think a black lesbian vampire storyâbenevolent or notâwas such a good idea politically. Some writer friends and activistsâAfrican American and lesbianâthought connecting the idea of vampires with vulnerable communities was too negative. Even as I explained that

The Gilda Stories

would be a lesbian-feminist interpretation of vampires, not simply a story about a charming serial killer, people found the idea hard to accept. The archetype of the vampire is so deeply imbedded in the culture it was difficult for a new vision to replace it, or so we thought.

I was anxious the first time I read a chapter at the Flamboyant Ladies Salon in Brooklyn, having no idea how people would respond to a tale of an escaped slave girl who becomes a vampire. The only thing I felt sure of was that the audience, assembled by founders Alexis DeVeaux and Gwendolen Hardwick for monthly salons in their home, would be kind. They were that and more. Their engaged, illuminating questions led me to do years of research on vampire mythology and women's relationship to blood and social history. Rereading Octavia Butler's work convinced me there was a place for women of color in speculative fiction. Chelsea Quinn Yarbro's books showed me that vampires could be more than opera-caped predators. Soon I published that first Gilda chapter in the

Village Voice.

After reading it, Joanna Russ sent me a post card of encouragement, which confirmed for me that lesbian feminism was a legitimate lens through which to develop an adventure story. Women's stories, long considered to reign only in the realm of the domestic, had been stepping out into the larger world for years. Yet few were grounded in such a traditional horror genre as vampires because that would require a complete reframing of the mythology itself.

What began with fury has become a decades long pursuit in search of meaningful responses to these political and philosophical questions: What is family? How do we live inside our power and at the same time act responsibly? How do we build community? How do we connect authentically across gender, ethnicity, and class lines?

A repeating refrain I wrote for

Bones & Ash,

the theatrical adaptation of this novel, is the spine upon which the story rests: “We take blood, not life, and leave something in exchange.” In order to answer any of the questions the book raises we must take bloodâmetaphorically speaking. That is, we must learn how to break through the surface, find the deep dangerous place where blood flows without hurting one other, and share all that we know and love in order to survive. This is a lifelong pursuit for all of us. I hope another couple of generations will take this journey with Gilda at their sides as I do.

Jewelle Gomez

July 2015

Louisiana: 1850

The Girl slept restlessly, feeling the prickly straw as if it were teasing pinches from her mother. The stiff moldy odor transformed itself into her mother's starchy dough smell. The rustling of the Girl's body in the barn hay was sometimes like the sound of fatback frying in the cooking shed behind the plantation's main house. At other moments in her dream it was the crackling of the brush as her mother raked the bristles through the Girl's thicket of dark hair before beginning the intricate pattern of braided rows.

She had traveled by night for fifteen hours before daring to stop. Her body held out until a deserted farmhouse, where it surrendered to this demanding sleep hemmed by fear.

Then the sound of walking, a man moving stealthily through the dawn light toward her. In the dream it remained what it was: danger. A white man wearing the clothes of an overseer. In the dream the Girl clutched tightly at her mother's large black hand, praying the sound of the steps would stop, that she would wake up curled around her mother's body on the straw and cornhusk mattress next to the big, old stove, grown cold with the night. In sleep she clutched the hand of her mother, which turned into the warm, wooden handle of the knife she had stolen when she ran away the day before. It pulsed beside her heart, beneath the rough shirt that hung loosely from her thin, young frame. The knife, crushed into the cotton folds near her breast, was invisible to the red-faced man who stood laughing over her, pulling her by one leg from beneath the pile of hay.

The Girl did not scream but buried herself in the beating of her heart alongside the hidden knife. She refused to believe that the hours of indecision and, finally, the act of escape were over. The walking, hiding, running through the Mississippi and Louisiana woods had quickly settled into an almost enjoyable rhythm; she was not ready to give in to those whom her mother had sworn were not fully human.

The Girl tried to remember some of the stories that her mother, now dead, had pieced together from many different languages to describe the journey to this land. The legends sketched a picture of the Fulani pastâa natural rhythm of life without bondage. It was a memory that receded more with each passing year.

“Come on. Get up, gal, time now, get up!” The urgent voice of her mother was a sharp buzz in her dream. She opened her eyes to the streaking sun which slipped in through the shuttered-window opening. She hopped up, rolled the pallet to the wall, then dipped her hands quickly in the warm water in the basin on the counter. Her mother poured a bit more bubbling water from the enormous kettle. The Girl watched the steam caught by the half-light of the predawn morning rise toward the low ceiling. She slowly started to wash the hard bits of moisture from her eyes as her mother turned back to the large, black stove.

“I'ma put these biscuits out, girl, and you watch this cereal. I got to go out back. I didn't beg them folks to let you in from the fields to work with me to watch you sleepin' all day. So get busy.”

Her mother left through the door quickly, pulling her skirts up around her legs as she went. The Girl ran to the stove, took the ladle in her hand, and moved the thick gruel around in the iron pot. She grinned proudly at her mother when she walked back in: no sign of sticking in the pot. Her mother returned the smile as she swept the ladle up in her large hand and set the Girl onto her next taskâturning out the biscuits.

“If you lay the butter cross 'em while they hot, they like that. If they's not enough butter, lay on the lard, make 'em shine. They can't tell and they take it as generous.”

“Mama, how it come they cain't tell butter from fat? Baby Minerva can smell butter 'fore it clears the top of the churn. She won't drink no pig fat. Why they cain't tell how butter taste?”

“They ain't been here long 'nough. They just barely human. Maybe not even. They suck up the world, don't taste it.”

The Girl rubbed butter over the tray of hot bread, then dumped the thick, doughy biscuits into the basket used for morning service. She loved that smell and always thought of bread when she dreamed of better times. Whenever her mother wanted to offer comfort she promised the first biscuit with real butter. The Girl imagined the home across the water that her mother sometimes spoke of as having fresh bread baking for everyone, even for those who worked in the fields. She tried to remember what her mother had said about the world as it had lived before this time but could not. The lost empires were a dream to the Girl, like the one she was having now.

She looked up at the beast from this other land, as he dragged her by her leg from the concealing straw. His face lost the laugh that had split it and became creased with lust. He untied the length of rope holding his pants, and his smile returned as he became thick with anticipation of her submission to him, his head swelling with power at the thought of invading her. He dropped to his knees before the girl whose eyes were wide, seeing into both the past and the future. He bent forward on his knees, stiff for conquest, already counting the bounty fee and savoring the stories he would tell. He felt a warmth at the pit of his belly. The girl was young, probably a virgin he thought, and she didn't appear able to resist him. He smiled at her open, unseeing eyes, interpreting their unswerving gaze as neither resignation nor loathing but desire. The flash-fire in him became hotter.

His center was bright and blinding as he placed his armsâone on each side of the Girl's headâand lowered himself. She closed her eyes. He rubbed his body against her brown skin and imagined the closing of her eyes was a need for him and his power. He started to enter her, but before his hand finished pulling her open, while it still tingled with the softness of her insides, she entered him with her heart which was now a wood-handled knife.

He made a small sound as his last breath hurried to leave him. Then he dropped softly. Warmth spread from his center of power to his chest as the blood left his body. The Girl lay still beneath him until her breath became the only sign of life in the pile of hay. She felt the blood draining from him, comfortably warm against her now cool skin.

It was like the first time her mother had been able to give her a real bath. She'd heated water in the cauldron for what seemed like hours on a night that the family was away, then filled a wooden barrel whose staves had been packed with sealing wax. She lowered the Girl, small and narrow, into the luxuriant warmth of the tub and lathered her with soap as she sang an unnamed tune.

The intimacy of her mother's hands and the warmth of the water lulled the Girl into a trance of sensuality she never forgot. Now the blood washing slowly down her breastbone and soaking into the floor below was like that bathâa cleansing. She lay still, letting the life flow over her, then slid gently from beneath the red-faced man whose cheeks had paled. The Girl moved quietly, as if he had really been her lover and she was afraid to wake him.

Looking down at the blood soaking her shirt and trousers she felt no disgust. It was the blood signaling the death of a beast and her continued life. The Girl held the slippery wood of the knife in her hand as her body began to shake in the dream/memory. She sobbed, trying to understand what she should do next. How to hide the blood and still move on. She was young and had never killed anyone.

She trembled, unable to tell if this was really happening to her all over again or if she was dreaming itâagain. She held one dirty hand up to her broad, brown face and cried heartily.

That was how Gilda found her, huddled in the root cellar of her small farmhouse on the road outside of New Orleans in 1850. The Girl clutched the knife to her breast and struggled to escape her dream.

“Wake up, gal!” Gilda shook the thin shoulder gently, as if afraid to pull loose one of the shuddering limbs. Her voice was whiskey rough, her rouged face seemed young as she raised the smoky lantern.

The Girl woke with her heart pounding, desperate to leave the dream behind but seized with white fear. The pale face above her was a woman's, but the Girl had learned that they, too, could be as dangerous as their men.

Gilda shook the Girl whose eyes were now open but unseeing. The night was long, and Gilda did not have time for a hysterical child. The brown of her eyes darkened in impatience.

“Come on, gal, what you doin' in my root cellar?” The Girl's silence deepened. Gilda looked at the stained, torn shirt, the too-big pants tied tightly at her waist, and the wood-handled knife in the Girl's grip. Gilda saw in her eyes the impulse to use it.

“You don't have to do that. I'm not going to hurt you. Come on.” With that Gilda pulled the Girl to her feet, careful not to be too rough; she could see the Girl was weak with hunger and wound tight around her fear. Gilda had seen a runaway slave only once. Before she'd recognized the look and smell of terror, the runaway had been captured and hauled off. Alone with the Girl, and that look bouncing around the low-ceilinged cellar, Gilda almost felt she should duck. She stared deeply into the Girl's dark eyes and said silently,

You needn't be afraid. I'll take care of you. The night hides many things.

The Girl loosened her grip on the knife under the persuasive touch of Gilda's thoughts. She had heard of people who could talk without speaking but never expected a white to be able to do it. This one was a puzzlement to her: the dark eyes and pale skin. Her face was painted in colors like a mask, but she wore men's breeches and a heavy jacket.

Gilda moved in her small-boned frame like a team of horses pulling a load on a sodden road: gentle and relentless. “I could use you, gal, come on!” was all Gilda said as she lifted the Girl and carried her out to the buggy. She wrapped a thick shawl around the Girl's shoulders and held tightly to her with one hand as she drew the horse back onto the dark road.

After almost an hour they pulled up to a large building on the edge of the cityânot a plantation house, but with the look of a hotel. The Girl blinked in surprise at the light which glowed in every room as if there were a great party. Several buggies stood at the side of the house with liveried men in attendance. A small open shed at the left held a few single, saddled horses that munched hay. They inclined their heads toward Gilda's horse. The swiftness of its approach was urgent, and the smell the buggy left behind was a perfumed wake of fear. The horses all shifted slightly, then snorted, unconcerned. They were eating, rested and unburdened for the moment. Gilda held the Girl's arm firmly as she moved around to the back of the house past the satisfied, sentient horses. She entered a huge kitchen in which two womenâone black, one white-prepared platters of sliced ham and turkey.

Gilda spoke quietly to the cook's assistant. “Macey, please bring a tray to my room. Warm wine, too. Hot water first though. Not breaking her stride, she tugged the Girl up the back stairs to the two rooms that were hers. They entered a thickly furnished sitting room with books lining the small bookshelf on the north wall. Paintings and a few line drawings hung on the south wall. In front of them sat a deep couch, surrounded by a richly colored hanging fabric.

This room did not have the urgency of those below it. Few of the patrons who visited the Woodard placeâas it was still known although that family had not owned it in yearsâhad ever been invited into the private domain of its mistress. This was where Gilda retreated at the end of the night, where she spent most of the day reading, alone except for a few of the girls or Bird. Woodard's was the most prosperous establishment in the area and enjoyed the patronage of some of the most esteemed men and women of the county. The gambling, musical divertissements, and the private rooms were all well attended. Gilda employed eight girls, none yet twenty, who lived in the house and worked hard hours being what others imagined women should be. After running Woodard's for fifteen years, Gilda loved her home and her girls. It had been a wonderfully comfortable and relatively tiny segment of the 300 years she'd lived. Her private rooms held the treasures of several lifetimes.

She raised the lid of a chest and pulled out a towel and nightshirt. The Girl's open stare brushed over her, nudging at the weight of the years on her shoulders. Under that puzzled gaze the years didn't seem so grotesque. Gilda listened a moment to the throaty laughter floating up from the rooms below, where the musical entertainment had begun without her, and could just barely hear Bird introducing the evening in her deep voice. Woodard's was the only house with an “Indian girl,” as her loyal patrons bragged. Although Bird now only helped to manage the house, many came just to see her, dressed in the soft cotton, sparely adorned dress that most of the women at Woodard's wore. Thin strips of leather bearing beading or quill were sometimes braided into her hair or sewn onto her dress. Townsmen ranked her among their local curiosities.

Gilda was laying out clothes when Macey entered the room lugging two buckets of waterâone warm and one hot. While stealing glances at the Girl, she poured the water into a tin tub that sat in a corner of the room next to an ornate folding screen.

Gilda said, “Take off those clothes and wash. Put those others on.” She spoke slowly, deliberately, knowing she was breaking through one reality into another. The words she did not speak were more important:

Rest. Trust. Home.

The Girl dropped her dusty, blood-encrusted clothes by the couch. Before climbing into the warm water, she looked up at Gilda, who gazed discreetly somewhere above her head. Gilda then picked up the clothes, ignoring the filth, and clasped them to her as she left the room. When the Girl emerged she dressed in the nightshirt and curled up on the settee, pulling a fringed shawl from its back down around her shoulders. She'd unbraided and washed the thickness of her hair and wrapped it tightly in the damp towel.

Curling her legs underneath her to keep off the night chill, she listened to the piano below and stared into the still shadows cast by the lamp. Soon Gilda entered, with Macey following sullenly behind holding a tray of food. Gilda pulled a large, overstuffed chair close to the settee while Macey put the tray on a small table. She lit another lamp near them, glancing backward over her shoulder at the strange, thin black girl with the African look to her. Macey made it her business to mind her own business, particularly when it came to Miss Gilda, but she knew the look in Gilda's eyes. It was something she saw too rarely: living in the present, or maybe just curiosity. Macey and the laundress, neither of whom lived in the house with the others, spoke many times of the anxious look weighing in Gilda's eyes. It was as if she saw something that existed only in her own head. But Macey, who dealt mostly with Bernice and some with Bird, left her imagination at home. Besides, she had no belief in voodoo magic and just barely held on to her Catholicism.