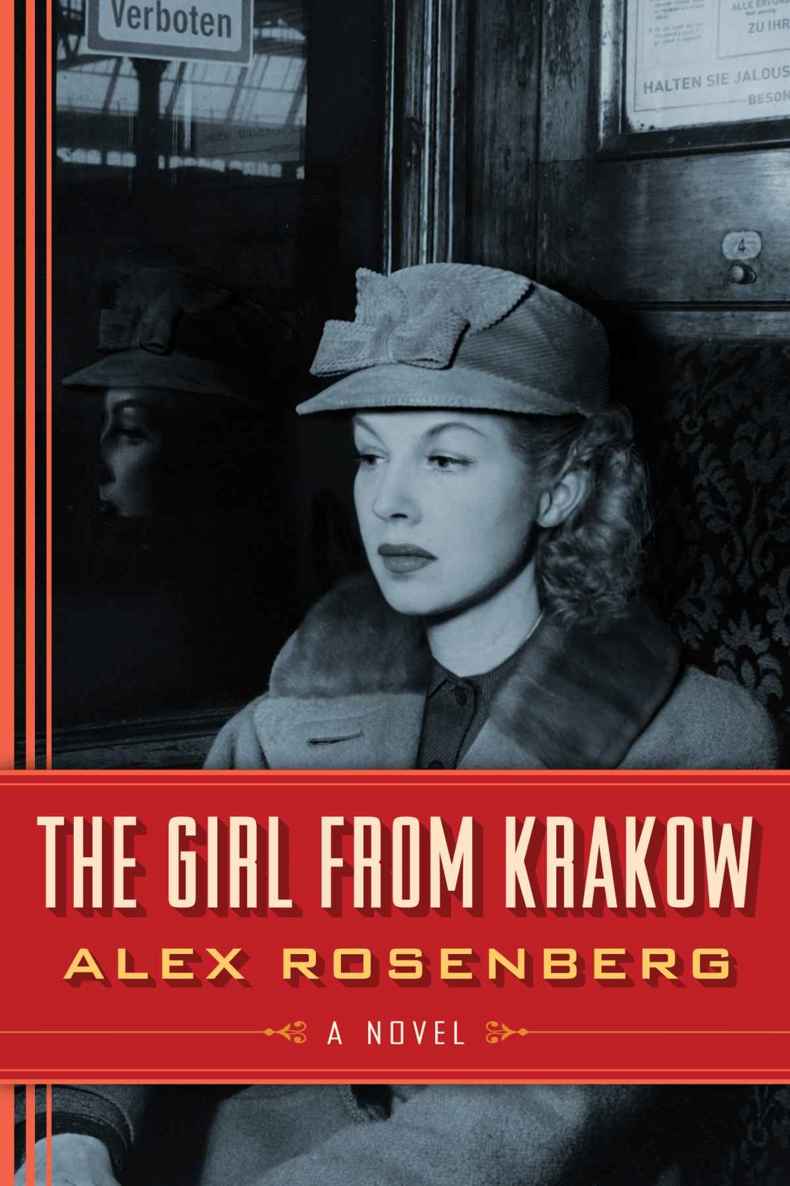

The Girl from Krakow

Read The Girl from Krakow Online

Authors: Alex Rosenberg

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, events, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Text copyright © 2015 Alex Rosenberg

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Lake Union Publishing, Seattle

Amazon, the Amazon logo, and Lake Union Publishing are trademarks of

Amazon.com

, Inc., or its affiliates.

ISBN-13: 9781477830819

ISBN-10: 1477830812

Cover design by Shasti O’Leary-Soudant / SOS CREATIVE LLC

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015900140

CONTENTS

IN MEDIAS RES

O

ctober 24, 1942.

Margarita Trushenko,

Volks-Deutsche

—ethnic German, from the east, almost an Aryan, and with papers to prove it—was on the quay, waiting for the 21:00 express to Warsaw. No, it wasn’t her. It was Rita Feuerstahl, trying hard to become Margarita Trushenko. It wasn’t going to be easy, Rita knew. In six years she’d never even been able to think herself into her married name. Inside she had always been Rita Feuerstahl.

How was she going to do this?

The German soldier checking documents at the platform barrier actually said

Danke

when she handed him the

Ausweis

, and again

Danke

after she had opened her case for inspection.

If you knew the truth, you’d sooner shoot me down than be

korrekt

.

A vacuum of fear was sucking at her intestines, the sort of cramps she had lived with through the first weeks of the occupation sixteen months before. Now it had started again—the dread, the feeling someone was playing Russian roulette with your life. She knew it would be constant for days or weeks. She decided to sit as near to the soldier on the quay as possible. A soldier offered protection. Rita

.

.

.

or rather Margarita Trushenko,

Volks-Deutsche,

needed it, waiting alone for the Lemberg train in a vast and empty train station at night. She took out the catechism booklet that had come with the forged baptismal certificate and tried to study it. Perhaps she’d be able to distract herself from the raging

angst

.

A few minutes later, an express came in from the west—from Berlin, Warsaw, Lemberg—full of officers and men on their way to join the victorious Wehrmacht

divisions in the Donbas, still cutting through whole Soviet army groups. Pretending to be fixed on her catechism, Rita didn’t notice the two Germans in civilian dress descending from the first-class carriage.

The German sentry did. He came to completely respectful attention as he examined their papers: one was an

Oberst

—a captain. The other was Friedrich von Richter, major general,

SS-RSHA

—Reich Security Main Headquarters, evidently traveling out of uniform. Of course, neither the sentry nor anyone else in Karpatyn that night could know that Richter wasn’t SS at all, but

Abwehr

, military intelligence and an officer in the first section, responsible for code security.

She could hear them clearly.

“Herr

Generalmajor

, there is no car awaiting you here,” said the sentry.

“We were not expected. Get on the telephone to Leideritz. Tell him to send a car immediately.” Evidently this man already knew the name of the SS

Obersturmführer

in charge of the town of Karpatyn. What he couldn’t know was that one reason he had come was sitting there on the platform waiting for a train in the opposite direction, Rita Feuerstahl. And she didn’t know she was the reason either.

Once the general’s car had left, the sentry came back onto the platform. Rita decided she should smile at him. He returned it with a look of complicity and a shoulder shrug, as if to say they were both better off beyond the penumbra of high-ranking officers. Rita’s eyes moved from him to the dark shape of the large station, then across the switching yards to the town beyond.

She knew that even if she survived, she would never come back. Nothing to return for—not her child, certainly not her husband, Urs. Her son was less likely to survive than she was. Urs’s odds in the Red Army medical corps were better, but it hardly mattered anymore. She had let him escape east, knowing he wouldn’t be strong enough to survive the Germans. Then she had tried to save their son, Stefan, by sending him out of the ghetto. But he was almost certainly already dead. The child had been the only bond cementing a marriage broken early by her adultery. Now, even if she and Urs both survived the endless war, there was nothing left between them.

She could have loved Erich, whom the occupation had brought into her life, if only he had let her. Yet he must have loved her in a way, for he left her with a secret so enormous that only love could have made him disclose it. She would not have believed what he told her except for his refusal to even try to save himself. Erich could have provided himself identity papers when he secured hers. Instead, he had allowed himself to be shipped with the last few hundred from Karpatyn to the extermination camp at Belzec.

Sitting there, under the dim lights of the quay, Rita still couldn’t decide if Erich had told her the truth or just a clever story to make her survive.

That night a week before, the final

Aktionen

had begun. After the news about her boy, Rita had been ready to end things. She still had the vial of potassium cyanide her husband had left behind. The Germans were going to win. The Reich would last a thousand years. She had no will to live. “Leave me to it, Erich.”

They were alone in the dark.

“No, Rita. The Germans will lose. It’s a matter of a few years—two or three, no more. And you will be alive to see it. I know something. But if I tell you, it could put Germany’s defeat at risk.”

“Well, then, keep it to yourself.”

“Listen, Rita. And then try to forget

.

.

.

End of September ’39, the Polish government came through Karpatyn—the commander in chief in his shiny boots, the prime minister, everyone—on the way to Romania. Well, one of the war ministry staff looked me up. We’d been close in Warsaw at the math faculty. He was carrying a typewriter case handcuffed to his wrist. And he told me why. The general staff had brought the case to the math faculty with a ‘typewriter’ inside it, in 1938. Only it wasn’t a typewriter; it was a German code machine. Some of the research students had been put to the task of figuring out how the machine worked and to crack the code. Well, they did it. They broke the code. We started to read German signals. Too late to help against their blitzkrieg in Poland, but with the ability to read the most secret German radio messages, the Allies can’t lose. Once they are fully mobilized, they have the key to winning the war. And you’ll be alive when they do.”

“But if they have the code, why has the German army cut through Russia like a scythe? What use has the code been to the Soviets?”

“The Reds don’t have it. The general staff wasn’t going to tell them when the Russians were Hitler’s allies in ’39. The secret is with the Brits, and they don’t trust Stalin any more than the Polish government did.” Rita nodded. “So, Rita, stay alive! Do anything to still be there at the end. Because it’s coming, and coming sooner than anyone realizes.”

“But if what you say is true, it would be crazy for me to know. The first time a policeman starts checking my documents, I could give it all away. It’s a story you’ve invented to save me, maybe to make up for my losing Stefan. You wouldn’t risk the whole outcome of the war—that would be madness

.

.

.

even if I believed you for a moment.”

“Believe me, Rita. What I have said is true. As to whether it’s crazy to tell you, well, there’s a line about that in your favorite philosopher, Hume.”

Now, looking down the tracks at the approaching train, Rita recalled the words again: “

’

Tis not contrary to reason to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger.” They had remained with her, puzzled her, amused her, disturbed her, ever since she’d first come across them.

PART I

BEFORE

CHAPTER ONE

C

ivil procedure was the first-year lecture course in the law faculty in Krakow. By November it had become as boring as it sounded. The only excitement Rita could still muster up for it was the frisson she felt three times a week as she edged through the narrow aisle to find her place in the lecture theater.

The nationalist students in the law faculty had taken to forcing the Jewish students to sit along one row of desks—the ghetto benches. When Rita chose to sit among the men in the ghetto benches, there were glares. The Green Ribbon bullyboys were taken aback to see the tall blonde girl sitting among the Jewish students. Some would lean back in their seats to call her a traitor, a Yid-lover, or worse, whispering that she was one of their gentile whores. Sitting there made her feel a bit heroic. It made student life a little more adventurous.

Still, after an hour, it was hard to keep awake in a hard seat high up in the unheated, ill-lit amphitheater. The sudden sound of the bell ending the lecture made Rita realize she had been dozing off.

An expensive nap

, she thought. She screwed the cap on her fountain pen, closed her notebook, and stretched. The last time she had looked up at the windows that ran around the room level with her seat high up the rear wall, the sky had been a uniform gray. But the sullen afternoon gloom had since turned a minatory black. Rita belted her trench coat. It was already too thin for the autumn weather, but cheaper than an overcoat and more fashionable.

What she needed was an hour in a warm café with her hands cupped around a large glass of tea. An espresso wouldn’t last long enough to warm her.

Never mind; both were luxuries Rita had become accustomed to denying herself. It wasn’t just the expense. Cafés were places to waste time arguing about politics. Each cult had its own table, a few even their own cafés. The only things the groups shared were a commitment to “free love” and a favorable ratio of young men to the few women students.

Moving slowly with the tide of bodies down the wide marble staircase, she suddenly felt herself being pulled down the steps by the loose end of her knotted trench-coat belt.

“Let go!” Loud and indignant, her voice turned several heads toward her, though not the one belonging to the elongated figure heedlessly drawing her down the steps. “What do you think you’re doing?” Rita yanked back on the belt hard enough that the hand at last released it, sending its owner stumbling down the last few steps.

Catching himself on the balustrade, the man turned toward her. “I’m so sorry. I was just reaching back to grab the end of my coat belt.” He looked down his frame at his open trench coat and then back up at her. “So crowded! Must have felt yours and just grabbed at it.”

“Well, you might look where you put your hands.” With that, Rita started down the stairs again. The man was still mumbling his excuses.

Rita passed through the broad lobby of the law faculty building. As she approached the doors, she glanced back. There he was again, right behind her—very tall, very thin, very young, she thought. His coat was now belted against the expected cold, and he was carrying a very heavy volume. He caught her eye and tried on a smile. Rita frowned back, turned, and strode toward the door.

Her pursuer was not discouraged. In the thinning crowd, he moved faster and was again finally beside Rita. “I’m so embarrassed,

Panna—

Miss

. .

. ?”

Rita did not supply her name. She was not in the mood to encourage him.

“Really,” he protested, “it was an innocent mistake. Could have happened to anyone. How can I apologize?”

“You already have. The matter is forgotten. Good night.”

Steps from the doors, the young man’s hand reached out to prevent her from moving on. Rita looked down at the hand on her arm, then slowly up at its owner. “This is getting to be a habit. Another apology coming?”

He immediately released her. “I’m rather stupid about these things. Look, I’m really sorry. Can I offer you a coffee to show my contrition?” He nodded toward the cafés across the street, crowded as the night fell. Now Rita noticed the heavy book under his arm, leather with gold lettering.

Pathology

. A medical text.

So

, she thought,

a Pole

. There were few Jews at the medical school.

The chill wind coming in through the open doors got the better of Rita. “A coffee?” She shrugged. “Why not?”

They came out of the faculty into the dark, accentuated by the wan glow of the streetlamps. It was cold, and they walked quickly to the largest of the cafés in the square. As they entered from the gloom, it was almost blindingly bright. On the walls Art Deco tracery framed mirrors that went from the wainscoting to the ceiling. Beneath the mirrors spread a sea of small round tables and bentwood chairs, filled by animated talkers. It was warm and suffused by a cirrus of aromatic Virginia tobacco smoke.

They moved toward the large white and blue porcelain stove at the rear, put their books on the table, and said, simultaneously, “What’s your name?” Laughing, they interrupted each other again, each answering over the other: “Urs, Urs Guildenstern.” “Rita Feuerstahl.” Then, for the third time, they spoke over one another’s words: “Nice to meet you, Rita” and “Funny, you don’t look like one—a bear, that is.” They fell silent for a moment, smiling as a waiter approached.

Urs looked from the waiter to Rita, who immediately said, “A large café au lait.” He was paying, and the breakfast-style coffee might just as well provide supper. Urs followed with, “Tea, please.”

As they waited, there was a chance to look each other over. He was still very tall sitting across from her. His lean cheeks were marked out by a tracery of small, dark points. Dark curly hair was already thinning back from a widow’s peak, despite his age, which she guessed at early twenties. But it was the long and narrow nose that dominated his features.

Looking at Rita, Urs saw a woman tall enough for him. Her blonde hair loose to the shoulders, straight, not bobbed. A lank of it curved down and across her rather broad forehead. Blue eyes and high cheekbones beneath fair skin made Rita look altogether more German or Ukrainian than anything else.

The drinks arrived. Rita began, “So, you are a medical student,” gesturing toward the volume on the table. He nodded, and she went on, “From Warsaw?”

“No, I’m from a town in the east.” Only now as Urs spoke could she detect a slight trace of eastern, in fact, Yiddish-inflected, Polish.

“But you’re Jewish,” she blurted. “How did you get into Polish medical school?”

“Hard work, and some luck, I guess. They do hold ten percent of the places for Jews.” He paused. “You’re actually the first Christian who’s twigged to my background before asking.”

“Well, that’s because I am the first Christian you’ve met who’s just another Yid.”

“No! I figured you for the complete

BDM

girl. Blonde, blue-eyed

.

.

.” Rita looked at him quizzically. Before she could ask, Urs explained. “

BDM

,

Bund Deutscher M

ä

del—League of German Girls

. It’s the female side of the Hitler Youth. So we’re both mistaking each other for what we are not. Shall we start again?”

“Actually, I’m relieved,” Rita confessed. “There are limits to my interest in assimilation, and I was sure you were Polish nobility.”

“Both our families can rest easy, I guess.”

By now Rita had warmed up. “So, what were you doing in the law faculty today? Trolling for Aryan-looking women law students?”

“No, I’m final year. We have to write a research paper. Mine’s on forensic medicine, and I needed to look up a case. What about you? Pretty pointless, a woman studying law, especially a Jew. No government posts: ‘No Jews, no women need apply.’ Politics interest you?”

“Not much,” she lied. “How about you? Interested in politics?”

“Just medicine, thank you.”

Rita smiled. “Smart. Seems to me men here get interested in politics mainly to meet girls. Anyway, I’m studying law because it’s the only faculty I could get into.”

“So, what will you do with the law?”

Rita shrugged. “I don’t know. Maybe nothing. Probably I’ll just go home when I’ve finished. But there’s always a chance

.

.

.

first-class marks on the examinations, catch the interest of a professor

.

.

.

There’s a chance.” Rita finished her coffee and then looked at her watch for an excuse to end the conversation and get away. “It’s late, and I have some work to do.”

Without thinking, Urs reached for her hand. “Can I see you again?”

“You can usually find me in the philosophy faculty library.” And she was gone.

Why did she tell him where she could be found?

Better stay away from there the next few days if you don’t want to see this guy again soon

.

Maybe she wouldn’t mind seeing him again. In any case, it would be hard to steer clear of the philosophy library. Even the glare of the other students, all men, could not keep her out. She enjoyed their looks of discomfort when they found a woman opposite them at the table reading Kant or Plato. It wasn’t so different from the looks of the law school bullyboys when she sat down among the men in the ghetto benches.

All too often, sitting there under the lamps breaking the gloom of the reading room, she’d lose the thread of what she was reading and begin to ask herself for the thousandth time the questions Urs had asked.

What exactly are you doing here, Rita? What did you really come for?

It wasn’t the law, not really.

She wanted a life. She wanted what any twenty-year-old did who knew she was very smart, almost beautiful, willing to take a chance, put her optimism to the test. She wasn’t going to find those tests in her father’s town or anywhere near it. Sometimes Rita wondered whether it was emancipation she yearned for or apostasy. At fourteen she had forced her parents to send her to the only girl’s gymnasium in town, operated by the Dominican sisters. By that time, in a school uniform, Rita was already tall, angular, looking out of place in her mother’s kitchen.

The required Catholic catechism class quickly confirmed her as an unbeliever. And atheism made it easy to reject her own culture’s patriarchy. But wasn’t it really just an excuse for doing something she wanted to do anyway: go her own way in life, not the one prescribed for her? Was it apostasy just to want to be yourself?

Be yourself? Who exactly was she, anyway?

Who is it, really, peering out at the world from inside my body, and why did it turn out to be me?

She had felt she needed to answer this question as far back as she could remember. She wasn’t going to in a small town in Silesia.

So she had announced an attachment to the law and come to Krakow.

Three days after their first meeting, there was Urs, at the bottom of the marble staircase of the fac’, waiting for the end of civil procedure. “I’ve been looking for you in the philosophy faculty library the last couple of days. That’s where you said you’d be.”

Rita was not really surprised. “I was indisposed. Studied in my rooms.”

Rooms?

As if I have more than one

, she laughed to herself.

“May I take you out for supper?”

Why not

, was her first thought, but she replied, “It’s a bit early

.

.

.

”

“I’ll come for you at seven o’clock. Just give me your address.”

“No. I’ll meet you. Tell me where.” She was not about to reveal where she lived. That would be much too forward, and the address was not nearly chic enough. For Rita, lodgings were a fifth-floor walk-up bedsit across the Vistula, in the only tenements poorer students could afford. The wallpaper was peeling, and the threadbare stair carpet covered treads that had been sagging since the nineteenth century. They groaned, even under her light step. Her room was no worse than most. A bed, a deal table and chair, a standing cupboard, a bureau on which sat a chipped but serviceable ewer and bowl, all illuminated by a bare electric bulb hanging from where a gas lamp used to shed a dimmer light. Plumbing had been installed on the floors below Rita’s, but the remains of an outhouse could still be seen at the back of what passed for a garden. Under the bed there was a chamber pot, nothing even the better-off weren’t used to. There was a gas ring for warming meals. The only real problem was the cold. Rita was always cold. Staying warm—enough coal in the grate—was dearer than life, and Rita could never afford it.

“How about Wierzynek?” he suggested. It was the best restaurant in Krakow, and it was warm.