The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (93 page)

Read The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 Online

Authors: Robert Middlekauff

Tags: #History, #Military, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

The march raised the mens' spirits but it did not change the advice of Washington's commanders. Lee continued to argue against taking on the enemy. Build them a bridge of gold, he said, to speed them on their way. Most of the others agreed, impressed as amateurs usually are by professional opinion. Anthony Wayne and Nathanael Greene, young and proud, urged an attack though they did not propose that Washington seek a general engagement. Steuben gave what was perhaps the wisest counsel of all -- strike Clinton when he was on the move

____________________

46 | Ward, II, 570-73; |

and off balance. Lafayette joined Steuben and pointed out that the long British baggage train was especially vulnerable.

47

Had Clinton attended the council of Washington's officers, he would have confessed that his long train was open to attack. Detachments under Maxwell and Dickinson had not yet ambushed his wagons, but they had made the going more difficult by breaking down bridges and the causeways over marshes. Clinton was aware of these shadows, and he soon got word that Washington had come out of Valley Forge. What worried Clinton most was the danger he would face at New Brunswick, where the Raritan would have to be crossed, where he might have to fight under dreadful circumstances. At the Raritan he feared he would have to face the combined forces of Gates -- who he thought was coming down from New York -- and Washington.

These odds seemed unpromising and, understandably, Clinton decided to turn at Allentown to the northeast on a route that would carry him through Monmouth Court House and Middletown to Sandy Hook and thus avoid the Raritan. This line of march could only be followed on one road and forced him to bring his troops and his wagons together. Between Gloucester and Allentown he had been able to use parallel roads and had placed most of his infantry between Washington and the baggage train. Now he had to consolidate his forces into one column -- the van, some 4000 under Knyphausen, followed by the long line of wagons, and to the rear 6000 troops -- the cream of the army, grenadiers and light infantry. Clinton detached about a third of these trailing soldiers and placed them under Cornwallis as a rear guard.

48

The British bit the road early on June 25 and reached Monmouth Court House, nineteen miles from Allentown, late the next afternoon. This move in brutal heat sapped their energies. Their soldiers carried packs of at least sixty pounds, weight made especially difficult to bear by sandy roads, woolen uniforms, and cumbersome muskets. The Hessians, who wore even heavier clothing than the English, suffered the most, several dying of sunstroke along the way. With his troops worn out and the hot weather holding on, per had to rest his army throughout the next day.

49

Washington also shifted his main force on June 25. He left his baggage and his tents at Hopewell and marched seven miles to Kingston, a small village three and one-half miles north of Princeton and twenty-five miles from Monmouth Court House.

The same day he sent Anthony Wayne

____________________

47 | GW Writings |

48 | Willcox, |

49 | Ward, II, 574. |

forward with 1000 regulars from New Hampshire -- Poor's brigade -- in order to strengthen the forces shadowing Clinton. The headquarters for this advance party was now at Englishtown about five miles west of the enemy's camp at Monmouth, but though the American van was close it was in fact divided into uncoordinated units. As if to remedy this, Washington pushed closer the night of the 25th, passing through Cranbury and pausing early the next morning within five miles of Englishtown. Like Clinton's army, the American rested on June 27.

While the troops ate, pulled their boots off, and slept, Washington brought several of his commanders to his headquarters. Among them was Charles Lee, who two days earlier had been persuaded to assume command of the advance force. Lee often appeared strange and eccentric to his colleagues and never more so than in these June days. Washington and Howe had agreed upon an exchange which freed him from British confinement in April, and in May he had returned to the American army at Valley Forge, where he was greeted with enthusiasm. While Lee was being held by the British he may have betrayed his American comrades by offering a plan of action to his captors, a plan designed, at least on its face, to end the war with a British victory. Since his return he had done little and when called upon for advice invariably couched it in language that left little doubt that he believed the American army could not stand up to the British. When, on June 25, Washington asked him to command the vanguard that trailed Clinton so closely, he at first refused and suggested that this task should properly go to Lafayette. Almost as soon as Lafayette accepted the command, now containing almost half the army, Lee changed his mind and asked that it be given to him. Washington agreed, and Lafayette generously gave way. Alexander Hamilton, who had watched these transactions with scorn, called Lee's behavior "childish." Whether or not that judgment was accurate, Lee's opposition to an attack on Clinton's army should have disqualified him from a responsible post.

50

Nonetheless Washington gave him command and on the 27th gave orders to attack the British rear when it began to move. The exact wording of the orders is not clear but whatever Washington said, his intention to bring on a partial engagement was plain. That he gave Lee discretion to avoid battle in extraordinary circumstances did not obscure this purpose. Washington provided no detailed instructions, however, as he had not reconnoitered the ground.

Nor had Lee, who on

____________________

50 | Freeman, |

returning to the advance force made no plan and gave no orders beyond a general statement to his subordinates that they must be guided by circumstances.

51

At five in the morning of June 28, Clinton started Knyphausen on the road to Middletown, about ten miles to the northeast. Dickinson, whose militia lay near to the British lead units, sent word immediately to Lee and Washington. Lee's units began moving from around Englishtown along the road to Monmouth Court House, and less than an hour later Clinton's rear began following the baggage train. The rear guard under Cornwallis was the last of all to move; it seems to have barely got on the road when units of Lee's cavalry discovered it. The battle that followed developed slowly as the two sides found each other and brought their troops to imperfect concentration.

52

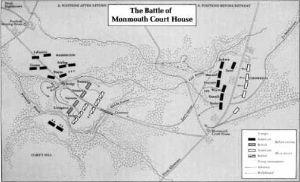

The terrain, largely unknown to the Americans and only slightly more familiar to the British, was in part responsible for the peculiar struggle that followed. Most of the ground was sandy pine barrens cut by small streams flowing through morasses and speckled by woods. Three fairly large ravines ran on a roughly east-west line just north of Monmouth Court House. They were West Ravine, Middle Ravine, and East Ravine. West Ravine and Middle Ravine were about a mile apart, and both were on the road. A bridge had been built over West Ravine and a causeway over Middle Ravine. East Ravine, which lay a little more than a mile east of Middle Ravine was also divided by the road.

53

The battle of Monmouth Court House began to take on serious proportions around this last ravine, just a mile north of the court house, as Lee's forces groped along the road. How the two sides actually engaged is not clear, but within an hour of noon almost 5000 Americans in no very ordered alignment nor in any fixed position, confronted around 2000 British, mostly infantry, under Cornwallis.

54

To this point the accounts of the battle are merely murky; after it they are confused and confusing. Artillery on both sides fired, and the American regiments evidently shifted their positions on the orders of their commanders and of Lee.

What Lee was about, he kept to himself,

____________________

51 | CW WlitingS |

52 | CW Writings |

53 | Ward, II, 577. |

54 | My account of the battle is constructed from |

though he did pull a part of his force back. Whatever he intended he simply produced uncertainty in Maxwell, Colonel Charles Scott, and Wayne on the left. A withdrawal on the right left them exposed, and they pulled their troops back. Within a few minutes the entire American force was in retreat. Several regiments seem to have kept their integrity and retired in good order. Others collided and mingled, giving the impression, largely accurate, that the withdrawal was a rout.

Almost all of the American commanders -- Wayne, Scott, Maxwell -reported a few days later that they had received no orders from Lee. He told neither them nor anyone else what should be done. As serious in their eyes was his failure to designate a line, or a position, from which a stand might be made. His accusers were unfair to him: Lee did not deliberately conceal his destination -- he did not know it. Shortly after the retreat began he sent Duportail, the French engineer, to reconnoiter a hill to the rear where perhaps a defense could be established. Dupdrtail followed orders, looked the hill over -- it was just west of Middle Ravine -- and pronounced it suitable. When Lee with his sweating army arrived at this hill, he found it less than desirable. Not far from it lay several others which would have given the British higher ground -- or so Lee conjectured.

Anthony Wayne with most of the troops in the advance pulled back in complete bewilderment. Wayne had not received an order to attack nor did he receive one to retreat. But he and Scott had withdrawn their forces after repeatedly begging Lee for reinforcements so they could attack, only to discover that the American right, to the south and east of the village, had disappeared. Wayne and Scott both believed that the Americans in the advance force outnumbered the British opposing them -- and they wanted to attack. Scott, a half-mile from the court house and well across East Ravine when the right evaporated, felt dreadfully exposed -- and was. The British cavalry does not seem to have discovered just how vulnerable he was as most of his troops lay concealed in woods. Still, Scott's regiments were nearly cut off and escaped only by filing off to the left under cover.