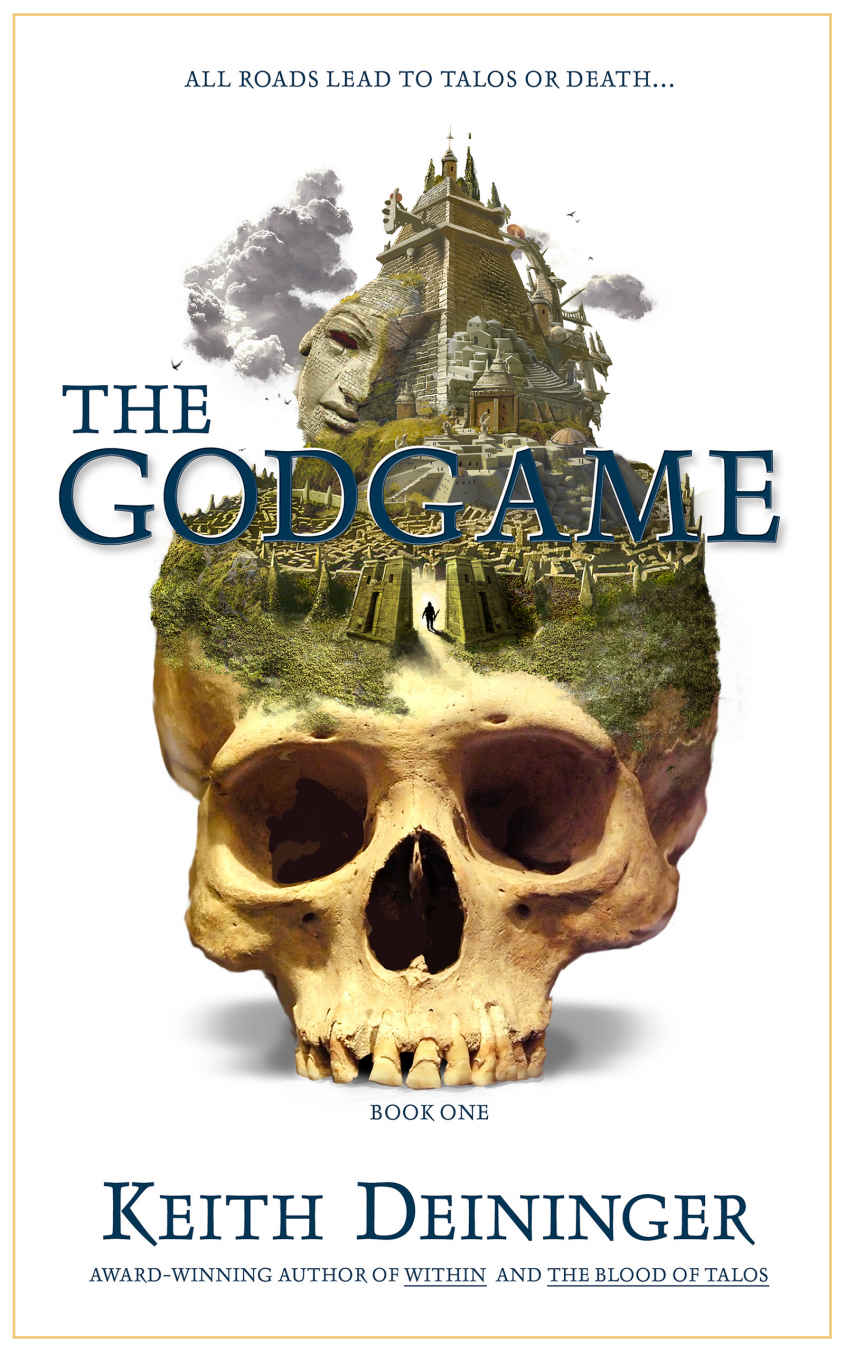

The Godgame (The Godgame, Book 1)

Read The Godgame (The Godgame, Book 1) Online

Authors: Keith Deininger

The Godgame

© 2015 by Keith Deininger

Cover design by

Sumrow Art and Illustration

Editor: Kari Sanders

This book may or may not be a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either a product of the author’s imagination or evidence of fictional realism. Any resemblance to actual events, locales or persons, living or dead, may or may not be entirely coincidental.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Get a free copy of the acclaimed Meridian Codex fantasy,

Shadow Animals

, when you sign up to join my Reader’s Group.

Click here to get started:

www.keithdeininger.com/get-a-free-book

“It is great good health to want to understand one’s dreams. It is great good health to desire the ambiguous and paradoxical. It is sickness of the profoundest kind to believe that there is one reality. There is sickness in any piece of work or any piece of art seriously attempting to suggest that the idea that there is more than one reality is somehow redundant.”

― Clive Barker

CITY OF TALOS

ELI

From endless storms to oceans vast, from arid wastes to the peak of this crimson mountain, his first glimpse came as the trolley shuddered upward and then, halting for a brief moment at the very top, plunged alarming down the other side. Yet even as his heart leapt into his throat, he could do nothing but stare through the cloudy window at what sprawled before him, filling every opening, every crevasse, every square of available space for as far as the eye could see…

The City of Talos.

It had been many days, yet each rise and fall of light might have been a year, a rebirth, an entire life lived in a series of awed gasps, and then darkness with the promise of new wonders on the morrow. For Eli Sol, who had only ever experienced the artificial lights of the Machine, each day the comet rose, filling the world with light and warmth, was a celebration.

He had fled blindly, a large part of him thinking he was as good as dead, doomed from the start—he would perish beneath the ceaseless rains of the Maelstrom. He had abandoned the safety of the Machine, of the world and the life he had always known, with only the vaguest of convictions and sense of duty. Outside of the Machine, there was nothing, they’d told him. The moldering letter from a distant ancestor, tucked in his breast pocket near his heart, provided his only instructions to the contrary. He carried a small pack slung over his shoulder containing a few scraps of clothing, some Machine-made energy cubes to sustain him, his threadbare copy of the LibroMachina, and the wooden box that had been passed down to him, from father to son for innumerable generations. The box was ornately carved, marked in a language he could not read. It held several strange items, including those long ago forbidden by his people. One of the items was an ancient weapon, a hand-held firearm, a “blunderblast” his father had called it, showing Eli its polished wooden grip when he’d been old enough.

“But the blunderblasts were banned by the Machine. They were all given to the furnace,” he’d said to his father, unable to tear his eyes from the dangerous weapon.

His father had smiled grimly. “A few were saved,” his father had said. “For the members of the Society of Saint Neil.”

“There are others?”

His father had looked away. “Yes, I believe so.”

“Who’s Saint Neil?”

“I don’t know.”

And that was all he could remember. His father, if he’d known more, having carried such knowledge to his death and to the furnaces of the Machine.

But there was another item in the box of far greater rarity and value than the blunderblast. It was smaller, its greatness less evident, easily missed among the other trinkets and clues: a tiny stub of paper, a ticket. It was to board the trolley that, according to the letter he carried, ferried travelers from the Machine to a place outside the Maelstrom.

And so he had fled the warmth of the Machine, almost certain his fate was to die alone and cold among the sharp and barren rocks beneath the unending torrent of rain from the Maelstrom above. If he did perish outside of the Machine, he knew, his body would be forever lost.

Will my soul be able to return to the Machine?

he wondered.

Will the Machine still allow my essence to recycle without my physical body to go with it?

He had only his ancient letter and box of archaic trinkets to guide him, these things and nothing left to lose.

Except my soul

, his mind insisted.

His family was gone, his daughter and his wife drowned, his friends killed when there had been a breach in the Machine’s foundation. In the depths where he worked, by the glow of the artificial lights, he had witnessed something that, after centuries of slow decay, had weakened and cracked, with a soft groan followed by a larger sound, an explosive scream of metal grinding against metal, exploding pipes, and then water that had gushed suddenly from deep below. He had been the only survivor.

He had awoken in the medical sector of the Machine. The doctors had told him sector nine was now completely beneath water. One of them, whispered out of earshot of the others, had also told him there were rumors of the water levels continuing to rise, slowly, but steadily.

He had been in shock for several days, stricken with grief. Only slowly had he remembered the ornately carved wooden box his father had given him and the letter that went with it. He had read it several times, dismissing its admonishments, expecting to dutifully pass it and the box on to his own son when he had one—or to Pia, his daughter, if he didn’t have a son—but he knew the letter mentioned something about “signs to look for” and “failings of the Machine.” It also said something about “The Flood.”

When he had recovered enough to return to his living quarters—lonely and sterile, which no longer possessed that feeling of

home

without his wife to lay her copy of the LibroMachina, which she’d been reading, down as he came through to door, to smile up at him from the couch—he had locked the door, slunk to the bedroom closet, and recovered the ancient box from its hiding place. He’d brought the box to the living room and stared at it. After a while, he’d carefully removed the letter from its envelope and opened it gingerly. It was soft like fabric, a burnt umber color. He’d read it by the glow of the light tubes that ran along the walls. When he was done, he’d read it again.

The Flood is coming…

And thus this suicide mission had begun. If his wife had been alive, or even one of his friends, he might have shared with her or him what he had been thinking of doing, but there had been no one. He could, of course, have gone to Father Etheridge—whose HaloMachina services were fierce preaching to the power and benevolence of the Machine—for advice, but then he would have had to admit to harboring contraband and the punishments for such crimes were severe.

He had, instead, left the Machine, his meager jacket instantly soaked beneath the rains of the Maelstrom that filled the sky with swirling eddies of gray. He had negotiated the treacherous rocks filled with crevasses eagerly opening before his stumbling feet, threatening to twist and snap the brittle bones in his ankles with every step. His progress had been slow and soon he’d been exhausted, but he’d forced himself onward. When he’d become too tired to continue, he’d hunkered down against the largest rock he could find, wrapped his arms tight about his shivering body, and passed into feverish sleep for an hour or two. Then he had eaten an energy cube, dragged his body up, and kept going.

At one point his feet had slipped out from under him and he’d fallen. He’d rolled onto his back and stared up into the rain.

My end has come

, he’d thought, just as he’d imagined it would, and he’d closed his eyes and intended not to rise again. But, sometime later, he had still been alive and found he still possessed some will to live. He’d risen, mustering himself, moving one foot forward, and then the other, and if he hadn’t, he never would have seen the wonders that were to fill the next several days.

Sometime later, just as his legs had begun to quiver uncontrollably, threatening to spill him to the rocks for the final time, he had come within sight of the trolley depot, a small building, its many windows shattered long ago. He’d realized then that a large part of him hadn’t believed he’d ever find it or that it had ever existed. He’d staggered into the depot, found a chair and passed into unconsciousness once again.

When he’d opened his eyes, the trolley had been pulled up to the station. He’d fumbled through his pack, unwrapping the wooden box from the plastic sheeting (made by the Machine) he’d used to protect it from the rain and, as if in a dream, watched his fingers sift through its contents. When he’d finally found the ticket, he’d rushed forward, afraid the trolley would leave without him. The door had been sealed shut, but there had been a thin slot much like those he’d seen in various places about the Machine. He’d slid the ticket carefully into the slot. There had been a shredding sound as the ticket was destroyed. His entire body had tensed as he waited. If he’d given the ticket to the wrong slot, there were no more in existence and he would have been left to die in that forlorn trolley station at the edge of the world.

But just as his heart had begun to sink, the door had begun to open, trundling aside reluctantly. He’d leapt through the opening. The door had shut behind him, and soon after the trolley had begun to move, slowly at first, and then faster and faster.

The next days he had spent gaping through the windows.

There wasn’t much to see in the trolley car, he’d soon come to realize. There were two rows of seats bolted to the floor with a narrow aisle between them. There were doors at either end of the car, but they were sealed shut. The walls were old metal, lined with round porthole windows of thick glass. Yet he was protected from the rain and the air was warm. There was little he could do other than to stare out one of the windows, but all he had been able to see at first was the Maelstrom, gray fog and rain. He’d closed his eyes and slept.

When he’d woken, what must have been several hours later, he had at first thought,

I must be dreaming

. He’d rubbed his eyes and stared. His mouth had fallen open, gawking.

Through the porthole window, outside of the train, he had seen light. It had been bright and shining unlike anything he’d ever experienced before, shimmering on the green surface of water that stretched infinitely into the distance.

He had spent the next several days unable to look away. The trolley had taken him skimming across the surface of an ocean mesmerizingly green and then a deep lapis, the sky a lighter shade of blue above, with only thin wisps of cloud to mar its surface. Then there had been land alive with greenery like he’d only ever seen in printed illustrations in books. He’d seen some sort of animal watching the trolley fly by with eyes huge and yellow. Then all around had been flat, green giving way to yellow grass that wavered in the breeze, and then to barren dirt pocked with craters. He’d seen bubbling pools of a substance thick and black, and strange-looking plants with needles growing from them. He’d seen slicks alive with flame and several odd creatures, one with a long snout and skin covered in protective scales; another with its body surrounded by a ponderous shell, dragging itself through the sand with claws that protruded from gaps at its sides. Days had passed and he’d forgotten his weariness; he’d forgotten to eat. Then the arid landscape had fallen behind and there had been another ocean and then mountains, the trolley climbing steadily upward.

The mountains had resembled the jagged rocks that surrounded the Machine, but unlike those rocks, these were covered in giant, leafless trees that crawled through their crevasses, clinging vermillion branches like constricting snakes. For endless hours, his sight through the cloudy porthole window had been filled only with these growths, with this singular flush of color, leaving his eyes strained and dry, as if they had begun to rust, forcing him to blink and look away.

And then the trolley had reached the apex of the mountain and every wonder he’d seen previously on his journey seemed to lose significance: he had reached his destination...

At the beginning of his journey, as he had climbed to the top of a small outcropping of rock just outside of the place he had always known as home, he had taken one last look back. He had gazed upon the Machine, built among the mountains. It was a towering compound, chamber built upon chamber, snaking interconnected corridors and observation domes. It stood massively, as it had always stood, its squealing gears grinding on and on, hissing steam, furnaces boiling, molten bubbling metals forged into all manner of strange objects, their purposes long forgotten. From the outside, it was an impressive sight, awe-inspiring, easily deified.

Yet now, as Eli stared through the trolley’s tiny window at the City, whose existence he had only a few days before thought impossible, he could not help but to think that if the divine engineers who had raised the Machine had one day focused all their ambitions on this sprawling valley, and for countless centuries thereafter worked tirelessly carving alcoves and building walls as the groundwork for these thousands of humble houses, gabled towers and ornate mansions—and if, after having erected a great pyramid of ascending steps whose peak rose higher than even the tallest of the Machine’s jutting pipework, they had built space for gardens and aviaries and astrological towers—then their efforts, once filled to overflowing with millions of scrambling citizens, might have approached the majesty and complexity of Talos.

The trolley caromed and shuddered along the track beneath his feet as Eli took in the immensity. Talos blanketed the landscape as far as the eye could see, rising in tangled heaps. It was an amazing sight. Everywhere a disorder of styles, structures on top of structures, accumulated ruins repurposed again and again, tier upon tier, angular platforms, precarious stairways, and towers of haphazardly stacked blocks. Everything covered in grime. If there was one distinguishing feature that defined Talos, it was its walls, parallel and perpendicular, some high and some low, some lined with spikes and others with twisting curls of razor wire, giving the City a labyrinthine quality. The hovels at the base of the gargantuan pyramid at the center of the City clung feebly to the outer walls like fungus from the earth. Further inward, the buildings became increasingly elaborate, yet always scuffed and worn-looking, from gated corridors lined with fine mansions, to domed structures, to groves of marble pillars, and then on to the highest peak, stairs that came to an apex upon which there appeared to grow a lush garden. Yet the pyramid was only a small section of Talos, the rest of the city and the geometry of its walls spreading like a purple and parasitic blight over the land, so that the actual center of the City must lie well beyond the base of the pyramid.