The Grand Ole Opry (33 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

IRVING WAUGH,

WSM president:

The Opry House wound up costing fifteen million dollars instead of the five million we’d projected. If we’d known that at

the beginning, we would never have done it. I’ve got this to say about National Life, though: while waves of nausea swept

over [president] Bill Weaver at times, he backed us all the way.

The rides and attractions of Opryland USA opened in May 1972. In January 1974, Bud Wendell became vice president of WSM and

the Grand Ole Opry and appointed former Opry announcer Hal Durham as Opry manager. Durham oversaw the move from the Ryman

to the new Grand Ole Opry House on March 15 and 16, 1974.

WSM press release, January 22, 1974:

The grand opening and first performance of the Grand Ole Opry in WSM’s new $15 million Opry house will take place March 16

before a capacity audience of regular Opry fans and music industry, civic, business, and government notables from across the

nation. The last Saturday evening performance of the Grand Ole Opry in the 84-year-old Ryman Auditorium, will be March 9,

and the last Friday evening performance will be March 15. The new 4,400-seat air-conditioned Opry house has been under construction

since November 12, 1971. It is the world’s largest broadcasting studio. It will be the first building to house the Opry that

was specifically designed and built for the 48-year-old radio show. The new Opry house has the world’s most advanced acoustical

and lighting systems, 12 dressing rooms, a band rehearsal room, and more than 12,000 feet of storage space. Television shows

can be produced in the auditorium or in the separate television production studio that has a seating capacity of 250. The

new Opry house is the centerpiece of Opryland U.S.A., National Life and Accident’s $26 million “theme” park.

The new Grand Ole Opry House, September 1974.

BASHFUL BROTHER OSWALD:

We was all hatin’ to leave. Roy Acuff figured it would be better to be out at Opryland. He said, “Boys, you’re gonna like

it out there,” and they didn’t all believe him. He said it would keep growing and be bigger all the time. He said, “Opryland

will draw a lot of people to the Opry.” But the Ryman had the best sound of anywhere I’ve ever played in my life. Course it

didn’t have no dressin’ rooms or anything, but that was all right. Saturday nights, I couldn’t wait to get down there and

see all the boys. You’d go backstage and you’d talk. Someone would say, “I didn’t make any money last week out on the road,”

and someone else would say, “Now I made a little. I’ll let you have some.” They don’t do that now.

GRANT TURNER:

The Opry is like an old department store with the stuff stacked in the aisles. You can move it to a nice new building, but

will the people still come? Nobody goes to a building, you know.

BARBARA MANDRELL:

I’m so very thankful I became a member of the Opry just before we moved into the big, beautiful Opry House. At the Ryman,

the girls had the restroom as a dressing room. Here were these huge stars . . . Dolly Parton, Tammy Wynette, Loretta Lynn

. . . sitting on toilets and visiting. We would all be perspiring so bad; it was so hot in there. But we were full of love

and passion for our music and the people who would come to see us.

left: The last night in the hot, crowded Ryman Auditorium.

right: Bashful Brother Oswald consoles Minnie Pearl after her last performance on the Ryman stage. Minnie Pearl: “I’ve tried

to be so bright because I know the audience will be so happy in the new home. Then tonight I was dressing and I had the radio

on, and they started talking about this being the last Saturday, and all of a sudden I was just

JEANNIE SEELY:

Oh, it was ungodly hot in the summer. One night, I guess it was August, I’d rolled my hair, fixed my makeup, and I walked

down the ramp, and, with the humidity and the perspiration, I could feel my hair flattening and my makeup running. I was mad

as hell. I stopped just short of the stage, and I said, “I’ve found out who you have to screw to get

on

the Grand Ole Opry, now who do you have to screw to get

off?”

But we all got to know each other. You’d bring a minimum of stuff with you ’cause there was just no room, and you’d share

stuff. The bond between the Opry artists might never have been formed this closely if we hadn’t been in the Ryman. It was

like a big family in a little house.

ROY ACUFF

to the last house at the Ryman, March 15, 1974:

Certainly there are memories of this old house that will go with us forever. Not all of them are good. Not all of them. Many

of them are. But some of them are punishment. Punishment in the way we ask you to come visit with us and then we sit you out

in the audience here and in the hot summer we sell you a fan for a dollar. You do your own air-conditioning. And some of you,

we sell you a cushion to sit on because the seats are just not the most comfortable they can be. But out in Opryland when

you come see us, we’ll furnish the air-conditioner. We’ll furnish the cushion seats.

HAIRL HENSLEY,

Opry announcer:

George Morgan, Lorrie’s father, was the star of the last portion of the Opry from the Ryman. The last song was his theme song,

“Candy Kisses.”

After “Candy Kisses,” the entire cast assembled to sing “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” Garrison Keillor, then an arts columnist

for the

New Yorker,

was in the auditorium that night. As a child, he’d heard the Opry in Minnesota.

GARRISON KEILLOR:

The best place to see the Opry that night, I decided, was in the [broadcast] booth with my eyes shut, leaning against the

back wall, the music coming out of the speaker just like radio. That good old AM mono sound. The room smelled of hot radio

tubes, and, closing my eyes, I could see the stage as clearly as when I was a kid lying in front of our giant Zenith console.

It was good to let the Opry go out the same way it had first come to me, through the air in the dark. After the show, it was

raining hard, and the last Opry crowd to leave the Ryman ran.

Inspired by the Grand Ole Opry, Keillor returned to Minnesota, and, on July 6, 1974, launched

A Prairie Home Companion

on Minnesota Public Radio. Like the Opry, it ran on Saturday evening and featured a mix of comedy and music. It was later

syndicated via NPR.

JEANNIE SEELY:

When we moved, a lot of people asked me, “Aren’t you afraid you’ll lose something?” Well, of course, leaving the Ryman was

sad, but I believe very much in a torch being passed and a responsibility being passed along with it. It was our responsibility

to make the new building mean what the people before us had made the Ryman mean.

BILL ANDERSON:

I felt instantly at home. I felt like this was where we were meant to be, and where we were going to be for the next many,

many years. I appreciate the Ryman. I loved everything that was down there, but if you were ever there on a hot night in July

with thousands of people blocking the entranceway to the building, and the temperature about 950 degrees backstage and no

air-conditioning, then you appreciate what we’ve got at the new Opry House.

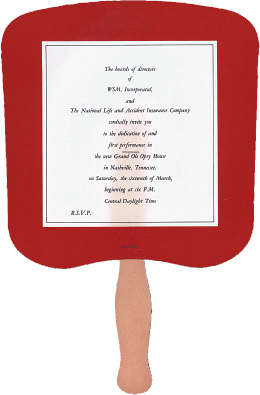

Invitation to the Opry House opening.

JEAN SHEPARD,

Opry star:

We done the Friday night Opry from the Ryman and the Saturday night Opry from Opryland. That Saturday night it sounded like

an Apache raid on a Chinese laundry. The sound was terrible. I come off the stage, and someone said, “Jean, how do you like

the new building?” I said, “I don’t like it at all.” But it’s gotten an awful lot better, it really has.

HAL DURHAM:

The last show at the Ryman was a matter of people grabbing up souvenirs and whatever they could find to remember the building.

The thought then was that it would be torn down. We got to the new building on Saturday and realized that we knew nothing

about it. We didn’t know where the restrooms were or the backstage was, and the first show involved a visit from President

Nixon. Of course, television was there, and the national press. Roy Acuff and his group opened the show, then we got to the

part where he invited the president to come down, and then we invited Opry members to come onstage.

President Nixon sat down at the piano and played “Happy Birthday” and “My Wild Irish Rose” to his wife, Pat, and then tried

to yo-yo with Roy Acuff.

PRESIDENT RICHARD M. NIXON,

on the Opry stage, March 18, 1974,to Roy Acuff:

I’ll stay here and try and learn to yo-yo, and you go be president for a while. Friends, country music speaks of family, our

faith in God, and we all know that country music radiates love of this nation, of patriotism. Country music, therefore, has

those combinations that are essential to America’s character at a time when America needs character. Your music makes America

better, and we come away better after hearing it.

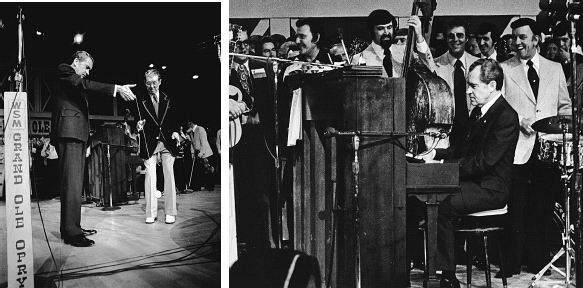

left: President Richard Nixon gets yo-yo lessons from Roy Acuff.

right: While many sitting presidents have visited the Opry, only Richard Nixon has actually played the Opry.

ROY ACUFF

to President Nixon:

He is a real trouper as well as one of our greatest presidents.

BILL ANDERSON:

I was standing onstage when Mr. Acuff and the president were out there playing with the yo-yos. I was next to Ernest Tubb,

and I thought, Well, here’s a man who’s been at the Grand Ole Opry since 1943, and I turned to him and said, “Ernest, did

you ever think you’d live to see the day when the president of the United States would come to the Grand Ole Opry?” He looked

at me and said, “No, but I wish it had been another president.”

The Opry crowd was quite possibly the last friendly audience that Richard Nixon encountered during his term in office. He

had been named a co-conspirator in the Watergate break-in by a federal grand jury the day before his appearance at the Opry.

On August 8, he announced that he would resign.