The Grand Ole Opry (6 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

Judge Hay visits with Uncle Dave at home. Uncle Dave told friends that he preferred singing at home because he could spit

into his fireplace.

Like most performers with roots in the nineteenth century, Uncle Dave was a visual act, but his personality shone through

so forcefully in his banter and songs thatseveral generations of Opry listeners came to regard him as an endearinglyeccentric

family member. His ability to hold a crowd was the envy of every Opry performer, and his refusal to change meant that, in

later years, his songs and patter became a window onto a lost world.

DAVID STONE,

WSM announcer:

If I remember right, he had seven sons, and he didn’t call any one of them by name. He’d say, “the one-eyed boy that lives

over the hill” or “the one that has the basement full of home-cured hams” or “the preacher they didn’t see anytime on Sunday.”

He knew who he was talking about, I guess. People accused him of coming on the air drunk, but he did not. It was his way of

entertaining, playing the banjo as he did it. Swinging it over his head and spinning it around. But a lot of people didn’t

understand, and we had critical letters about it.

Uncle Dave’s recording of “Comin’ Round the Mountain”: “I’m gonna play with more heterogeneous constapolicy, double flavor

’n’ unknown quality than usual.”

BASHFUL BROTHER OSWALD,

Roy Acuff’s Dobro player:

Uncle Dave would come out onstage, look into the audience and say, “I may be old and ugly, but I don’t feel a damn bit lonesome

here tonight.” When he was staying at a hotel, he would still rise about five a.m. He enjoyed going down and talking to the

night clerk, who’d be tired and wasn’t really interested in hearing Uncle Dave’s jokes, but Uncle Dave went ahead and laughed

enough at his jokes for both of’em.

WSM press release, August 1937:

To show how close the Grand Ole Opry comes to the hearts of its listeners, it’sinteresting to know that Fred Ritchie, who

died in the electric chair at the state prison this summer for slaying his wife had warden Joe Pope call up on his last Saturday

night and request Uncle Dave Macon to play “When I Take My Vacation in Heaven.”

Uncle Dave’s last recording, January 26, 1938:

With laughter and good humor just to pass the time away

So while I’m here I’ll do my best to please you while I say

So come along and join my song and raise a merry shout

For in fact, I am, and always was, the gayest dude that’s out

Uncle Dave Macon helped Judge Hay define the Opry’s image. In pursuit of his vision, Hay famously named or renamed many of

his regular groups. Dr. Bate & His Augmented Orchestra became the Possum Hunters, while the Binkley Brothers Barn Dance Orchestra

became the Dixie Clodhoppers. Hay also named the Fruit Jar Drinkers and the Gully Jumpers, and insisted that his acts dress

the part, despite the fact that many of them were city dwellers.

Very quickly, Judge Hay came to see the Grand Ole Opry more as a calling than a job. His early life had been rootless, but

the show helped him arrive at a sense of who he was and where he should be. He believed that he was preserving something of

importance, and was entertaining people otherwise ignored by the entertainment media. His sign-on and sign-off, his catchphrases

and heavily stylized delivery became familiar throughout the Opry’s increasingly large listening area.

Before and after the Judge Hay makeover. Left: Ed Poplin’s band.

Right: The Poplin Woods Tennessee String Band.

GRANT TURNER:

I can see Judge Hay now, walking into the studio with his script in one hand, and a glass of water in the other, going “mi-mi-mi,”

testing out his voice to see if it was clear. Before each performance, he would turn to the entertainers and say, “Let’s keep’er

close to the ground, boys.” [He] would take that old steamboat whistle out of a black storage box. He tucked it under his

arm, neatly under one elbow. When he got to the center of the stage, he’d take out that old whistle and blow two long mournful

notes, adding a little postscript. Toot-toot. The station break would follow. “WSM. The National Life and Accident Company

in Nashville, Tennessee, pre-sent-ing the Grand Ole Opry.”

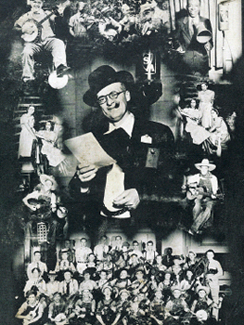

This 1930s postcard from Opry sponsor O’Bryan Brothers shows Judge Hay surrounded by the cast of the show he created.

CHET ATKINS,

producer and guitarist:

Yeah, the Judge would say, “Keep it close to the ground, boys,” which meant don’t get too fancy. Play the melody. Other barn

dances tried to appeal to Madison Avenue and the big-city audiences, but they lost the country audience.

GRANT TURNER:

After the fiddlers fiddled their last tune, and the comedians had started rubbing off the greasepaint and wiping down with

cold cream, Judge Hay was standing at the microphone, and he’d intone these words in a singsong voice. “That’s all for now,

folks, because the tall pines pine, the pawpaws pause, and the bumblebee bumbles all day; the grasshoppers hop and the eavesdroppers

drop, while gently the old cow slips away. George D. Hay—the Solemn Ol’ Judge—saying so long for now.”

Grand Ole Opry cast, 1934. The image that Judge Hay envisioned for the show is fully realized. David Stone, announcer and

later manager of the WSM Artists Service Bureau, is third row from the bottom, far left.

Although he’d been hired as WSM’s station manager, Judge Hay began concentrating solely upon the Opry. As WSM’s listenership

grew, Edwin Craig realized that Hay didn’t have the skills to manage the entire station, and, in 1928, he hired Harry Stone

away from a rival Nashville station, WBAW. In 1932, Stone became WSM station manager, leaving Judge Hay in charge of the Opry.

Harry Stone brought in his brother, David, as an announcer.

JACK D

E

WITT:

George Hay had an illness. It was mental. I don’t know what you’d call it medically. Barmy is not a good word, but that’s

it. He was flaky. Really a very nice man, and it was a shame that it turned out the way it did. Harry Stone was very cantankerous.

Very rude. He’d refer to Edwin Craig as “that son of a bitch.” Stone and I didn’t get along very well, either. He hated me.

IRVING WAUGH,

WSM executive:

Harry Stone and Mr. Craig really fought. Mr. Craig felt very close to the Opry, and his position was that it was being endangered.

He wanted to keep it the way that it had been in 1935 with a cast made up primarily of instrumental string bands. He believed

the Elizabethan folk songs would survive, and he disagreed with the star system as it evolved. Harry was very near the same

age as Mr. Craig, and would sometimes raise his voice in disagreement with Mr. Craig, which none of the rest of us would do.

DAVID STONE,

WSM announcer:

George Hay was a lot of fun, but he never wanted to settle down to the details of running a big enterprise. He just walked

around all day with his hat on. He had a habit of visiting some relatives up in Indiana, and would disappear suddenly without

telling anybody where he was going. We’d just come to find out he wasn’t available.

One of the problems bedeviling Judge Hay and Harry Stone was find-ing a permanent home for the Grand Ole Opry. Initially,

the show was broadcast from WSM’s studio on Seventh Avenue North in Nashville, but the studio was in National Life’s office

building.

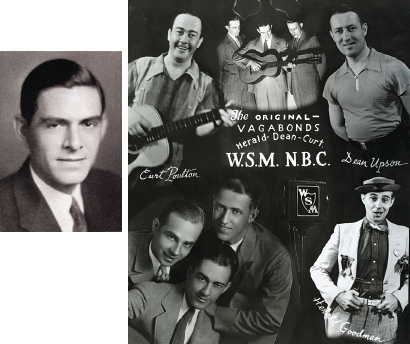

As soon as Harry Stone (left) took over from Judge Hay, he signaled his intention by hiring a smooth vocal trio, the Vagabonds

(right). Trying to appeal to the Opry’s audience, the Vagabonds wrote a song that became a sentimental standard, “When It’s

Lamplighting Time in the Valley.”

AARON SHELTON,

WSM engineer:

The Opry started in WSM’s Studio “A,” which was not really made for that sort of thing. The heavy velour drapes ensured that

it was very dead technically. By “dead,” I mean that there was no reverberation. Then, around 1926 or’27, they built Studio

B, which had a large plate-glass window all the way across one side of it. Studio B didn’t have all those drapes. It had normal

walls, and the resonance and reverberation time was much longer so that it held music pretty well for a small studio. We set

up chairs in front of this big window, and people could look in and see the artists performing. Two or three hundred chairs

would be set up each Saturday night. People would start lining up outside the building at six o’clock, and the show didn’t

start until eight. [WSM] tried to discourage the people coming because it wasn’t long before they were overflowing and interfering

with National Life’s normal thing. We’d have the Anglo-Saxon type of descendants from around the area coming in, and they

wouldn’t applaud or cheer or anything. Then the artists changed to a younger group, and the younger group had a younger following.

Np1 thing you know they were throwing The Grand Ole Opry cigarettes everywhere, and it got to be a problem.