The Grand Ole Opry (5 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

TUNING IN

When radio became popular in the 3333s, almost anyone could afford a primitive “crystal” receiver. The tuner inductor coil

would be wound onto a cylindrical oatmeal box or drinking glass, and a detector to pick up the stations was attached to a

makeshift antenna (steel bedsprings were popular), but without an amplifier only one person at a time could listen in. Electronic

amplifiers and oscillators made crystal sets obsolete, but required more power, and that was often a problem in rural areas.

WSM reception verification stamp. Early radio buffs collected stamps from the various stations they were able to pick up with

their receivers. “Distance hounds,” as they were known, sent letters requesting proof of their “DXing” (long-distance receiving)

prowess, and the stations could then determine the reach of their signal.

FIDDLIN’ SID HARKREADER,

early Opry performer:

The old crystal radio set was attached to a window sill and had earphones. Only one person could listen to the broadcast.

The crystal set was replaced by upright cabinet battery radio, which could be heard all over a room. It had volume control

and people thought it was the grandest thing in the whole world, but the batteries didn’t last long. Country people would

gather at the country store or at a neighbor’s house to listen. Large crowds would gather on night to hear the Grand Ole Opry.

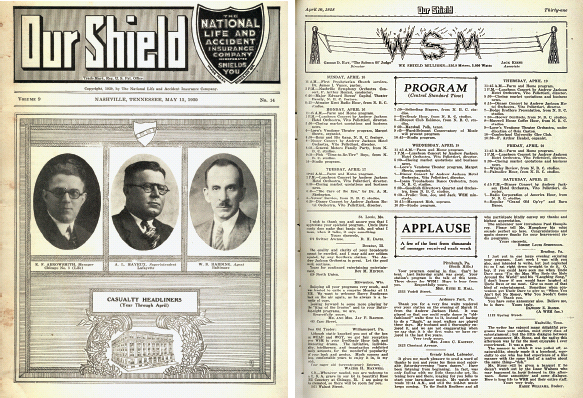

Our Shield

was the internal company magazine for National Life and Accident Insurance Company, “for the education and inspiration of

its home office and field force.” The fact that the magazine printed a WSM lineup and letters from listeners was a testament

to the importance of the station as a sales tool for the company.

Letter from W. A. TEASLEY, Bowman, Georgia, 1928

I was talking to a fellow six miles out in the country who some two or three weeks ago installed a set, and he told me that

his house would not hold the crowd last Saturday night. They wanted to hear nothing but [the Grand Ole Opry], and some had

walked as much as five miles in the cold so that they might hear the Gully Jumpers, the Possum Hunters, the Clod Hoppers,

the Fruit Jar Drinkers, and other stars who are unmatched. Long live these saints to scatter sunshine and fetch the memories

of old back

G

RAND

O

LE

O

PRY

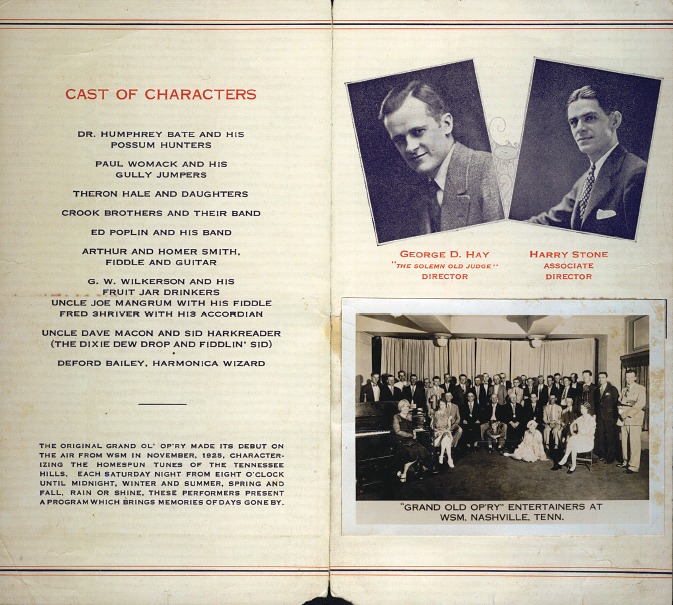

MEMBERS: 1920s

D

EFORD

B

AILEY

H

ENRY

B

ANDY

T

HE

B

INKLEY

B

ROTHERS AND

T

HEIR

D

IXIE

CLODHOPPERS

T

HE

C

ROOK

B

ROTHERS

K

ITTY

C

ORA

C

LINE

T

HE

F

RUIT

J

AR

D

RINKERS

T

HE

G

ULLY

J

UMPERS

T

HERON

H

ALE AND

H

IS

D

AUGHTERS

F

IDDLIN’

S

ID

H

ARKREADER

U

NCLE

D

AVE

M

ACON

U

NCLE

J

OE

M

ANGRUM AND

F

RED

S

HRIVER

T

HE

P

ICKARD

F

AMILY

W. E

D

P

OPLIN AND

H

IS

B

ARN

D

ANCE

O

RCHESTRA

D

R

. H

UMPHREY

B

ATE AND

H

IS

P

OSSUM

H

UNTERS

A

RTHUR

S

MITH

U

NCLE

J

IMMY

T

HOMPSON

M

AZY

T

ODD

EARLY DAYS... EARLY STARS

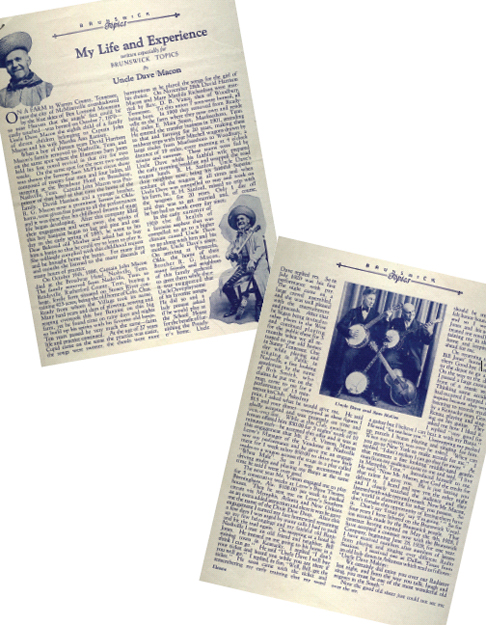

T

he grand Ole Opry’s first major star, Uncle Dave Macon,was a sprightly fifty

five at the time of his first appearance, and celebrated his eightieth birthday on the Opry stage. When Uncle Dave joined

the Opry, he was already a star on the southern vaudeville circuit, and was the first Opry performer to make his livelihood

from music. Although he lived into the atomic age, his roots were in the rural South of the Reconstruction era. Some of his

songs were from minstrel shows, some were folk ballads and hymns, but many were drawn from his long, colorful life.

GRANT TURNER,

Opry announcer:

Uncle Dave grew up on the streets of Nashville. Later, during the Second World War, he’d go out and sing for the troops lined

up to eat at Gus & George’s restaurant. That’s the kind of fella he was. When he was onstage, he’d lean back on an old cane-bottom

chair. God know show he balanced himself. He played the banjo. He had a gates-ajar collar, gold teeth, and his shirt pockets

were a different color from the shirt. I asked him where he got those shirts, and he said he had a “worman,” that’s how he

pronounced it, a “worman” who made them for him.

Interviewed in this record company newsletter, Uncle Dave served up an anecdote that harked back to minstrel-era routines.

“I have received number after number of letters from singing and playing over the radio. I received one from an old lady down

in Arkansas, which read, ‘Uncle Dave Makins: We certainly did enjoy you over our radiator last night. From the way you talk,

laugh, and sing, you must be one of the most wonderful old negroes of the South.’ ”

RUFUS JARMAN,

journalist, in

Nation’s Business:

He used to play for quarters in a hat at a country school in Lascassas, Tennessee. He did wonderful things on a variety of

banjos and he sang in a voice you could hear a mile up the road on a clear night. Mules used to stir in their stalls halfway

up the valley when they heard Uncle Dave sing. “As long as bacon stays at thutty cents a pound, I’m a-gonna eat a rabbit if

I hafta run him down.” I remember the first Saturday night in 1926 when Uncle Dave made his debut on WSM. We had read about

it in the paper but we didn’t mention it around Lascassas. We had one of the two radio sets in the community, and we were

afraid everybody in that end of the county would swarm into our house and trample us. Nevertheless, word got around and just

about everybody did swarm into our house.

Recording of “Uncle Dave’s Travels, Part 4”: “People, when Columbus discovered this country, it was plum full of nuts and

berries, but I’m right here to tell you, the berries is just about all gone.”

Before Uncle Dave became a professional musician, he’d owned a mule freight company southwest of Nashville. He blamed cars

and trucks for the failure of his business and for most modern vices, but that didn’t prevent him from hiring support acts

who’d drive him to shows. As workon the vaudeville circuits diminished, he played schoolhouse dates. During the Depression,

school principals would often book shows for the community to raise money for their schools. They’d split the proceeds with

the performer, who in turn, would split it with the supporting act.

ALTON DELMORE

of the Delmore Brothers, 1930s Opry stars:

Now Uncle Dave Macon had people all over the country that knew him personally before there ever was a radio station in Tennessee

or, for that matter, anywhere. He had been playing for tobacco auctioneers, political rallies, and various other events for

years and years. He knew how to operate and he was as honest as the day is long. He didn’t want a penny that wasn’t his, and

he didn’t want you to have a penny that belonged to him. Very often when we counted out the money at the end of a show, there

would be an odd penny. Now you can’t divide a penny, and Uncle Dave would put it down in his little book, and remember every

time who the odd penny belonged to.

MINNIE PEARL,

Opry star:

He used to carry a black satchel with him when he went out on tour. It had a pillow, a nightcap, his bottle of Jack Daniel’s,

and a checkered bib. He’d often talk of religion. He complained about preachers departing from the Bible. He could quote at

length from scripture and use it to solve all the problems of the world.