The Great American Steamboat Race (2 page)

Read The Great American Steamboat Race Online

Authors: Benton Rain Patterson

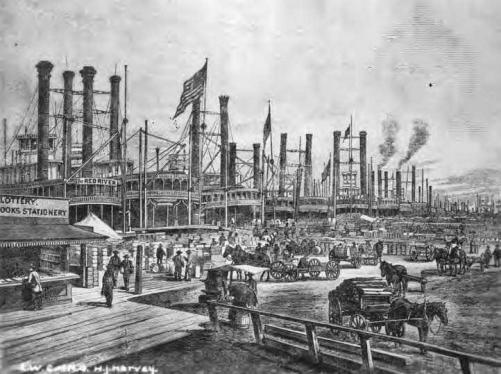

Steamboats lined up at the New Orleans wharves around 1870. Mark Twain captured the excitement of such New Orleans riverfront scenes in his classic work,

Life on the Mississippi

(Library of Congress).

Everyone along the river, in towns, villages and cities and the spaces in between them, had heard about it, as had a great many in cities far from the banks of the Mississippi, across the country and across the seas. The race had captured the attention and imagination of almost everybody. And most of those nestled in the huge crowd of spectators, white and black, employer and employee, rich and poor, man and woman, boy and girl, had a favorite they were pulling for. All were expecting to see the beginning of the race of the century, pitting two of the biggest, speediest and best-known packets against each other, the

Natchez

versus the

Robert E. Lee

, running from New Orleans to St. Louis, twelve hundred river miles, as fast as their huge paddle wheels — and their captains — could drive them.

The early-twentieth-century steamboat historians Herbert and Edward Quick, who lived at a time that was close to America’s steamboating era, evinced the feelings of many people of those days:

To those who merely looked on, a steamboat race was a spectacle without an equal. To the people of the lonely plantations on the reaches of the great river, the sight of a race was a fleeting glimpse of the intense life they might never live. To see a well-matched pair of crack steamboats tearing past, foam flying, flames spurting from the tops of blistered stacks, crews and passengers yelling — the man or woman or child of the backwoods who had seen this had a story to tell to grandchildren.

2

The people of New Orleans, of course, where the race would start, were especially fascinated, even obsessed. The

Picayune

declared, “The whole town is given up to the excitement occasioned by the great race.... Enormous sums of money have been staked here on the result, not only in sporting circles but among those who rarely make a wager. Even the ladies have caught the infection, and gloves and bon bons, without limit, have been bet between them.”

3

Among the people of New Orleans the

Natchez

was believed to be the favorite, it being considered a New Orleans boat and its owner being a year-round New Orleans resident.

In other cities along the Mississippi and Ohio interest in the race was almost equally high as in New Orleans. The

New York Times

reported from Memphis that “the excitement over the race between the

R.E. Lee

and the

Natchez

is intense. The betting is heavy, with the odds in favor of the

Lee

.” In St. Louis, it reported, “The excitement over the steam-boat race is very great here this evening, and large amounts of money are staked....” And in Cincinnati: “The race between the steamers

Natchez

and

R.E. Lee

, on the Mississippi River, has created more of a sensation here today than anything of the kind that ever occurred. There has been a great deal of betting. Between $100,000 and $200,000 have doubtless been staked.”

4

There is no way of knowing how enormous was the total sum bet on the race, but it easily rose into the millions. Professional gamblers were having a field day. In New Orleans before the race began, they were giving odds on the

Robert E. Lee.

Seventy-five-dollars bet on the

Natchez

would return one hundred dollars if it beat the

Lee

.

More than bets were at stake, though. Winning a head-to-head race, and thereby establishing itself as the fastest steamboat on the river, would be a public relations and marketing windfall, potentially bringing new freight and passenger business to the winner, and increased profits along with it. Losing the race, particularly if by a considerable time, would be a humbling if not humiliating experience for both the boat and its crew, and possibly a costly one in lost future revenue.

Some of the backers of the race, influentials who had helped persuade the

Robert E. Lee

’s reluctant owner and captain, John W. Cannon, to agree to the contest, had still more in mind. The steamboat business was in a state of

Thomas P. Leathers, owner and captain of the

Natchez

. Gruff, quick-tempered and physically imposing, Leathers had an intimidating presence and was determined to drive the

Robert E. Lee

off the Mississippi River (National Mississippi River Museum and Aquarium, Captain William D. Bowell Sr. River Library).

decline and had been since the Civil War. The cause was railroads, which over their ever-expanding network of lines could carry passengers and freight faster, cheaper and to and from more destinations than could steamboats. Some steamboat owners who could remember the golden years of the 1840s and 50s thought there was a way to bring back the good times, if only shippers and passengers could have their attention diverted from trains back to the elegant floating palaces that steamboats had been before the war. A race between two of the western rivers’ best and fastest steamers — a gigantic publicity stunt — just might help the steamboat business gain new friends and regain old ones that had been lost to the railroads.

The most critical element of the race, however, was the heated rivalry between the boats’ owner-captains — tall, powerfully built, craggy-faced, fiftyfour-year-old Thomas P. Leathers of the

Natchez

and intense, husky, soft-spoken, fifty-year-old John W. Cannon of the

Robert E. Lee

. Both men were Kentucky natives, Leathers having been born in Kenton County, near Covington, Kentucky, and Cannon near Hawesville in Hancock County, on the Ohio River. Both had long experience with steamboats.

At age twenty Leathers

had signed on as mate on a Yazoo River steamer, the

Sunflower

, captained by his brother John. In 1840, when he was twenty-four, he and his brother built a steamboat of their own, the

Princess

, which they operated on the Yazoo and later on the Mississippi, running between New Orleans, Natchez and Vicksburg. The brothers soon built two other steamers,

Princess No. 2

and

Princess No. 3

, and prospered with them on the Mississippi. In 1845 Leathers built the first of a series of steamers that he named

Natchez

, each larger and faster than the previous one.

The third

Natchez

, large enough to carry four thousand bales of cotton, met with tragedy when a wharf fire engulfed it and destroyed it, taking the life of Leathers’s brother James, who was asleep in his stateroom. The fifth

Natchez

, capable of carrying five thousand bales of cotton, was the boat that transported Jefferson Davis to Montgomery, Alabama, where he was sworn in as the Confederacy’s president in 1861. It was operated by Leathers until it was pressed into service by the Confederates, first as a troop carrier and then as a cotton-clad gunboat on the Yazoo River, its works shielded by a wall of cotton bales. On March 23, 1863, twenty-five miles above Yazoo City, Mississippi, it was set ablaze and destroyed by its crew to prevent its capture by Union forces.

Following the fall of New Orleans in 1862, Leathers temporarily gave up the steamboat business. After the war, he returned to the river and in 1869 launched from its Cincinnati shipyard a brand-new

Natchez

, the sixth, of which he was immensely, even overbearingly, proud. He was confident — and boastful — that it could beat anything on the Mississippi.

When in his twenties, he had made his home in Natchez and there he had met Julia Bell, the daughter of a steamboatman, and he married her in 1844, when he was twenty-eight. Julia became a victim of yellow fever, and Leathers had then married Charlotte Celeste Claiborne of New Orleans, member of a prominent Louisiana family that included a former governor, William C.C. Claiborne. Leathers moved from Natchez and made his home in New Orleans, where he and Charlotte began raising a family and where he spent the Civil War years.

Gruff, hard-faced, quick-tempered and physically imposing, Leathers could be intimidating to his workers and to others. Once a steamboat mate, he never got over the use of the profanity-filled language that mates routinely used to drive their crews. Through his years as owner and captain, his mate’s vocabulary never left him, and along the river he became notorious for it.

Somewhere during his career Leathers picked up the nickname of “Ol’ Push,” which according to one account was a shortened form of the name of the heroic, nineteenth-century Natchez Indian chief Pushmataha, whom Leathers and his crew sort of adopted as the symbol and mascot of the

Natchez

, which they liked to call “the big Injun.” The nickname, however, could just as easily have been inspired by Leathers’s pushy personality. With his fast new

Natchez

he developed the irksome habit of letting other steamers shove off from the New Orleans wharves ahead of him, then while his excited and cheering passengers watched along the rails, he would make a grand show of speeding up and overtaking whatever lesser vessel had moved out into the river before him.

Leathers pulled that stunt once on John Cannon’s good friend John Tobin, when Tobin was master of the steamer

Ed Richardson

. Tobin never forgot the incident. He got his chance for revenge when he became captain of the third

J.M. White

, a big, new boat that had never been tested in a race. On a day that Tobin had been waiting for, the

Natchez

and the

J.M. White

were together at the New Orleans waterfront and backed off from the wharf about the same time. The speedy

Natchez

quickly moved out ahead and gained a lead while an accident aboard the

J.M. White

forced it to slow down so that repairs could be made. Once the repairs were completed, Tobin ordered the steam up, and the

J.M. White

, its powerful wheels churning against the current of the muddy Mississippi, glided abreast of the

Natchez

, then overtook it. Leathers, seeing he was beaten, pretended he needed to make a stop to unload freight and thus had to drop out of the contest. The freight that he unloaded was an empty barrel, which he reportedly kept aboard the

Natchez

to be used for just such embarrassing occasions.

Leathers’s attitude toward his steamboat business, which he managed with meticulous care, and his position in life were revealed in a story told about him by one of his fellow captains, Billy Jones of Vicksburg. Leathers, Jones claimed, would often refuse to accept the freight for a shipper or a consignee he didn’t like, and the firm of Lamkin and Eggleston, a wholesale grocery company in Vicksburg, was one of the shippers he didn’t like. When he declined to accept their freight, the firm sued him in circuit court and won a judgment against him. The judgment was upheld in the state supreme court, and Leathers had to pay the firm $2,500 in damages, which infuriated him. “What’s the use of being a steamboat captain,” he fumed in frustration, “if you can’t tell people to go to hell?”

5

John Cannon, in personality, attitude and some other ways, was completely unlike Tom Leathers. Placid-faced, calm, quiet, he was a careful and far-sighted businessman who seemed more interested in the safety of his boat and passengers than in a showy display or establishing grounds for boasting. But like Leathers, he was a Kentucky farm boy who determined he would make something of himself. As a youngster he paid for his education with money earned by splitting rails. He began his life on the Mississippi aboard a flatboat and deciding the river was where he would pursue his fortune, he became a deckhand on a Red River boat and later a cub pilot on a Ouachita River steamer, the

Diana

, paying his pilot tutor out of the wages he earned working at a variety of jobs aboard the boat.

In 1840 he completed his training and became a licensed pilot. With money he saved from his pilot’s pay and with the help of several friends he built the steamer

Louisiana

, which came to a tragic end on November 15, 1849, when its boilers exploded at the Gravier Street wharf in New Orleans, taking eighty-six lives and shattering the two steamers docked on either side of the

Louisiana

. That experience likely affected his way of thinking about endangering other boats of his. Recovering from that disaster, Cannon went on to build or buy a dozen or more steamers, including the

S.W. Downs

,

Bella Donna

,

W. W. Farmer

,

General Quitman

,

Vicksburg

,

J.W. Cannon

,

Ed Richardson

and the

Robert E. Lee.

The

Robert E. Lee

was built for Cannon in New Albany, Indiana, in 1866, the year after the end of the Civil War, and it was designed to be the most luxurious and fastest boat on the western rivers. When it came time to paint its name on the boat, an explosive problem arose. The display of the name of the South’s most famous general inflamed many of the people in New Albany and elsewhere, and Cannon had to have the unfinished boat towed across the Ohio River to the Kentucky side to prevent its being burned by enraged Indiana citizens, whose feelings were expressed in an editorial published in the Rising Sun, Indiana, newspaper, the

Record

, shortly before the race : “The people hereabouts who are interested in the race are friendly to the Natchez for many reasons. A steamer named for any accursed rebel General should scarcely be allowed to float, much less have the honor of making the best time....”