The Hare with Amber Eyes (13 page)

Read The Hare with Amber Eyes Online

Authors: Edmund de Waal

I can believe this. Anna seems to have been able to create trouble wherever she went. On the family tree my grandmother made for my father in the 1970s, there are pencil annotations. Anna has two children, she writes, a beautiful daughter who marries and then flees with her lover to the East, and a son who is ‘not married, did nothing’. ‘Anna’, she continues, ‘witch’.

Eleven days after Anna’s wedding to her banker, Stefan, the heir-apparent – groomed for the life of the bank, with his fantastic waxed moustaches – elopes with his father’s Russian Jewish mistress Estiha. Estiha only spoke Russian – this is written on the annotated family tree –

and broken German.

Stefan was immediately disinherited. He was to receive no allowance, live in no family property, communicate with no member of the family. It was a proper Old Testament banishment, admittedly with the particularly Viennese slant of marrying your father’s lover. One sin piled on another: apostasy on filial disgrace. And linguistic incompetence in a mistress. I’m not sure how to read this. Does it reflect badly on father or son, or both?

Cut off, this couple went first to Odessa, where there were still friends and a name to use. Then on to Nice. Then a succession of progressively less smart resorts along the Côte d’Azur as their money ran out. In 1893 an Odessa newspaper notes that the Baron Stefan von Ephrussi has been received into the Lutheran Evangelical faith. By 1897 he is working as a cashier in a Russian bank for foreign trade. A letter comes from a shabby Paris hotel in the 10th arrondissement in 1898. They have no children, no heirs to complicate Ignace’s plans. I wonder, in passing, if Stefan kept his fine moustaches as he travelled downwards with Estiha through these circles of shabbier hotels, waiting for a telegram from Vienna.

And Viktor’s world stopped still as a slammed book.

Café mornings or not, Viktor was suddenly going to be in charge of a very large and complex international business. He was to be blooded in stocks and shipments, sent to Petersburg, Odessa, Paris, Frankfurt. Precious time had been lost on the other boy. Viktor had to learn quickly what was expected of him. And this was just the start. Viktor also had to marry, and he had to have children: specifically he had to have a son. All those dreams of writing a magisterial history of Byzantium were lost. He was now the heir.

I think it might have been at around this point that Viktor developed his nervous tic of taking off his pince-nez and wiping his hand across his face from brow to chin, a reflex movement. He was clearing his mind, or arranging his public face. Or perhaps he was erasing his private face, catching it in his hand.

Viktor waited until she was seventeen and then proposed to the Baroness Emmy Schey von Koromla, a girl he had known since her childhood. Her parents, Baron Paul Schey von Koromla and the English-born Evelina Landauer, were family friends, business associates of his father’s, neighbours on the Ringstrasse. Viktor and Evelina were close friends, as well as contemporaries in age. They shared a love of poetry, would dance together at balls and go on shooting parties to Kövecses, the Scheys’ Czechoslovakian estate.

The young scholar: Viktor, aged 22, 1882

Viktor and Emmy were married on 7th March 1899 in the synagogue in Vienna. He was thirty-nine and in love, and she was eighteen and in love. Viktor was in love with Emmy. She was in love with an artist and playboy who had no intention of marrying anyone, let alone this young decorative creature. She was not in love with Viktor.

Alongside appropriate wedding-presents from all over Europe, laid out after the wedding breakfast in the library, was a famous rope of pearls from a grandmother, the Louis XVI desk from cousin Jules and Fanny, the two ships in a gale from cousin Ignace, an Italian Madonna and Child

nach

Bellini in a huge gilt frame from uncle Maurice and aunt Béatrice, and a large diamond from someone whose name is lost. And, from cousin Charles, there was the vitrine containing the netsuke lined up on the green velvet shelves.

And then, on 3rd June, ten weeks after the wedding, Ignace died. It was sudden: there was no malingering. According to my grandmother, he died in the Palais Ephrussi with Émilie holding one hand and his mistress the other. This must have been another mistress, I realise, a mistress who was neither his son’s wife nor one of his sisters-in-law.

I have a photograph of Ignace on his deathbed, his mouth still firm and decisive. He was buried in the Ephrussi family mausoleum. It is a small Doric temple that he had built with characteristic foresight to hold the Ephrussi clan in the Jewish section of the Vienna cemetery, and where he had his father, the patriarch Joachim, reinterred. Very biblical, I think, to be buried with your father, and to leave space for your sons. In his will he left legacies to seventeen of his servants, from his valet Sigmund Donnebaum (1,380 crowns) and the butler Josef (720 crowns) to the porter Alois (480 crowns) and the maids Adelheid and Emma (140 crowns). He asked Viktor to choose a picture for his nephew Charles from his collection, and suddenly I see a tenderness here, a remembrance from an uncle of his young bookish nephew and his notebooks forty years before. I wonder what Viktor found amongst all the heavy gilt frames.

And so Viktor, with his new young wife, inherited the Ephrussi bank, responsibilities that laced Vienna together with Odessa and St Petersburg and London and Paris. Included in this inheritance was the Palais Ephrussi, sundry buildings in Vienna, a huge art collection, a golden dinner service engraved with the double E, and the responsibility for the seventeen servants who worked in the Palais.

Emmy was shown round her new apartment, the

Nobelstock

, by Viktor. Her comment was to the point. ‘It looks,’ she said, ‘like the foyer of the Opera.’ The couple decided to stay upstairs on the second great floor of the Palais, a floor with fewer painted ceilings, less marble around the doors. Ignace’s rooms were kept for the occasional party.

The newly married couple, my great-grandparents, have a balcony view onto the Ringstrasse, a balcony view for the new century. And the netsuke – my sleeping monk flat over his begging bowl and the deer scratching his ear – have a new home.

The vitrine needs to go somewhere. The couple have decided to leave the

Nobelstock

as a monument to Ignace; and Viktor’s mother Émilie, thank God, has decided to go back to her grand hotel in Vichy, where she can take the waters and be horrible to her maids. So they have a whole floor of the Palais for themselves. It is already full of pictures and furniture, of course, and there are the servants – including Emmy’s new maid, a Viennese girl called Anna – but it is their own.

After a long honeymoon in Venice they have to make some decisions. Should these ivories go in the salon? Viktor’s study isn’t quite big enough. Or the library? He vetoes his library. In the corner of the dining-room next to the Boulle sideboards? Each of these places has its own problems. This is not an apartment of the ‘most pure Empire’, like Charles’s delicate calibrations of objects and pictures in Paris. This is an accumulation of

stuff

from four decades of affluent shopping.

The great glass case of beautiful things has a particular difficulty for Viktor, as it comes from Paris, and he doesn’t want it sitting and reminding him of an elsewhere, another life. The thing is that Viktor and Emmy are not quite sure about Charles’s gift. They are wonderful, these little carvings, funny and intricate, and it is obvious that his favourite cousin Charles has been exceedingly generous. But the malachite-and-gilt clock and the pair of globes from cousins in Berlin, and the Madonna, can be placed straight away – salon, library, dining-room – and this great vitrine cannot. It is too odd and complicated, and it is also rather large.

Emmy at eighteen, startlingly beautiful and fabulously dressed, knows her mind. Viktor defers to her concerning where all these wedding-presents should go.

She is very slim with light-brown hair and beautiful grey eyes. She has a sort of luminosity, that rare quality of someone who is at home in the way she moves. Emmy moves beautifully. She has a good figure and wears dresses that show off the narrowness of her waist.

As a beautiful young baroness, Emmy has the full hand of social accomplishments. She has been brought up in two places, in the city and in the country, and has the skills for both. Her childhood in Vienna was in the Scheys’

Palais

, an austere piece of grand neoclassicism, a quick ten minutes’, walk away from her new home with Viktor, facing out across to the Opera over a statue of Goethe looking extremely cross. She has a charming younger brother called Philippe, universally known as Pips, and two little sisters Eva and Gerty, who are still in the nursery.

Until she was thirteen, Emmy had a meek and biddable English governess, who was keen to keep the peace in the schoolroom. And then nothing. Her formal education is full of terra incognita as a result. There are great swathes about which she knows practically nothing – history being one – and she has a particular laugh when these things are mentioned.

What she does know are her languages. She is charming in both English and French, which she speaks interchangeably at home with her parents. She knows any number of children’s poems in both languages and can quote great sections of “The Hunting of the Snark” and ‘Jabberwocky’. And she has her German, of course.

Every weekday afternoon in Vienna since she was eight has included a dancing hour, and she is now a wonderful dancer, a favourite partner at balls for ardent young men, not least for that waist tied with a bright sash of silk. Emmy can skate like she dances. And she has learnt how to smile with interest as her parents’ friends talk about opera and theatre at the late suppers they give, this being a household where business is not to be discussed. There are lots of cousins in their lives. Some of them, like the young writer Schnitzler, are rather avant-garde.

Emmy knows how to listen with a particular animation, sensing when to ask a question, when to laugh, when to turn away with the tilt of her head to another guest and leave her interlocutor looking at the nape of her neck. She has a lot of admirers, some of whom have experienced her sudden squalls. Emmy has a considerable temper.

For this life in Vienna she needs to know how to dress. Her mother, Evelina, only eighteen years older, also dresses impeccably and wears only white. White all year round: from her hats to the boots that she changes three times a day in the dusty summer. Clothes are a passion that her parents have indulged her in, partly because Emmy has an aptitude for them.

Aptitude

is too flat a description. It is more driven, more vocational, this way she has of changing one part of what she is wearing to make herself look different from other girls.

There was a lot of dressing up in Emmy’s youth. I found an album from a weekend party where the girls had been photographed dressed up as characters from Old Master paintings. Emmy is Titian’s Isabella d’Este in velvet and fur, while other cousins are pretty Chardin and Pieter de Hooch servant-girls. I make a note of Emmy’s social dominance. Another photograph shows the handsome young Hofmannsthal and the teenage Emmy dressed up as Renaissance Venetians at a wedding masque. There was also a party where they all dressed up as characters from a Hans Makart painting, the perfect opportunity for wide-brimmed hats with feathers.

Before and after marriage Emmy’s other life is in Czechoslovakia, at the Schey country house in Kövecses, two hours by train from Vienna. Kövecses was a very large and very plain eighteenth-century house (‘a large square box such as children draw’, in the words of my grandmother) set in a flat landscape of fields, with belts of willows, birch forests and streams. A great river, the Váh, swept past, forming one of the boundaries to the estate. It was a landscape in which you could see storms passing far away and never even hear them. There was a swimming lake with fretted Moorish changing huts, lots of stables and lots of dogs. Emmy’s mother Evelina bred Gordon setters – the first bitch arriving in a slatted crate on the Orient Express, the great train stopping at the tiny halt on the estate. And there were her father’s German pointers for the shooting – hares and partridge. Her mother enjoyed shooting and, as the time of a confinement grew nearer, used to go out on the partridge shoots with her midwife following her as well as the gamekeeper.

In Kövecses, Emmy rides. She stalks deer and shoots and walks with the dogs. As I struggle to bring the two parts of her life together, I am also slightly aghast. My picture of Jewish life in

fin-de-siècle

Vienna is perfectly burnished, mostly consisting of Freud and vignettes of acerbic and intellectual talk in the cafés. I’m rather in love with my ‘Vienna as crucible of the twentieth century’ motif, as are many curators and academics. Now I am in the Vienna part of the story, I am listening to Mahler and reading my Schnitzler and Loos, and feeling very Jewish myself.

My image of the period certainly doesn’t stretch to include Jewish deer-stalking or Jewish discussion of the merits of different gun-dogs for different game. I am at sea, when my father rings me up to tell me that he has found something else to add to the growing file of photographs. I can tell that he is rather pleased with himself and his own vagabonding on this project. He comes down to my studio for lunch and produces a small white book from a supermarket bag. I’m not sure what it is, he says, but it should be in your ‘archive’.

The book is bound in very soft white suede, sunned and worn away on the spine. The cover bears the dates 1878 and 1903. It is closed with a yellow silk ribbon, which we untie.

Inside are twelve beautiful pen-and-ink images of members of the family on separate cards, each edged with silver, each with its own carefully designed frame in Secessionist patterns, each with a cryptic quatrain in German or Latin or English, part of a poem or a snatch of a song. We work out that it must be a present for Baron Paul and Evelina’s silver wedding anniversary from Emmy and her brother Pips. White suede for their mother, who was always so particular about white: hats, gowns, pearls and white suede boots.

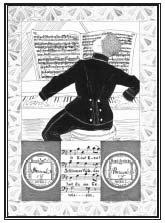

One of the silver anniversary pen-and-ink cards is of Pips in uniform playing Schubert at the piano: he has received the education that Emmy never had, with proper tutors. He has a wide circle of friends in the arts and the theatre, is a man around town in several capitals and is as impeccably dressed as his sister. A childhood memory of my great-uncle Iggie’s was seeing into Pips’s dressing-room at a hotel in Biarritz where they all spent a summer. The door of the wardrobe was open, and hanging on a rail were eight identical suits. They were all white: an epiphany, a vision of heaven.

Pips playing the piano. An image from Joseph Olbrich’s Secessionist album, 1903

Pips appears as the protagonist of a highly successful novel of the time by the German Jewish novelist Jakob Wassermann, a sort of Mitteleuropa version of Buchan’s Richard Hannay in

The Thirty-Nine Steps

. Our aesthetic hero is a pal of archdukes and manages to outshoot anarchists. He is erudite about incunabula and Renaissance art, rescues rare jewels and is loved by everyone. The book is viscous with infatuation.

Another pen-and-ink sketch in this album shows Emmy dancing at a ball, leaning back as a slim young man leads her round the floor. A cousin, I presume, as this willowy dancer is most certainly not Viktor. One drawing shows Paul Schey almost obscured by the

Neue Freie Presse

, an owl sitting in deep reserve behind him on his chair. Evelina skating. A pair of legs in striped bathing shorts disappearing into the swimming lake at Kövecses. Each picture also contains a little image of a bottle of eau-de-vie or wine or schnapps and a few bars of music.

The cards are the work of Josef Olbrich. He was the artist at the heart of the radical Secession movement and designer of its pavilion in Vienna with an owl relief and a golden dome of laurel leaves, a quiet, elegant place of refuge with walls that he described as ‘white and gleaming, holy and chaste’. Since we are in Vienna, where everything is subject to intense scrutiny, it also receives vitriol. It is the grave of the Mahdi, say the wags, the crematorium. That filigree dome is ‘a head of cabbage’. I give Olbrich’s album suitable scrutiny, but it is a lost acrostic puzzle, utterly unknowable. Why the eau-de-vie, why that piece of music? It is very Viennese, an urbane view of their country life in Kövecses. It is a window into Emmy’s world, a whole warm world of family jokes.

How could you possibly not know you had this? I ask my father. What else have you got in the suitcase under your bed?