The History of Florida (82 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

river channels that once ran to the ancient coastline.

As sea levels rose over thousands of years, Florida’s landmass changed,

becoming the shape we are familiar with today. The first Floridians utilized

the coasts to obtain maritime resources, such as fish and shellfish, for food

and tools. Inland freshwater springs continued to be of major importance,

and evidence of native use can stil be found in many spring basins and sink-

holes. For example, at Little Salt Spring hundreds of objects made of wood,

shel , bone, and stone have been recovered and provide information about

· 389 ·

390 · Del a A. Scott-Ireton and Amy M. Mitchell-Cook

proof

Prehistoric canoes, such as this one recovered near Weedon Island,

often are found along Florida’s waterways. Courtesy of the Pinellas

County Communications Department.

the people who lived around the spring in the late Paleoindian and early

Archaic Periods (11,400–10,200 YBP [Years Before Present]). One especial y

amazing artifact appears to be an early calendar with incised markings rep-

resenting the days of the month, one of the earliest date-keeping tools ever

discovered in North America.

Watercraft appeared in Florida as early as the middle to early Archaic

Period (at least 7,000 to 6,000 YBP); although earlier watercraft probably

existed, archaeological evidence has not yet been found. Some Archaic ves-

sels have been discovered, however, and currently more than 300 wooden

dugout canoes have been identified in the state. Primarily discovered during

The Maritime Heritage of Florida · 391

droughts when lakes dry up and river levels are low, canoes offer a rare

glimpse of the first maritime activity in Florida. For example, in the sum-

mer of 2000, a severe drought exposed dozens of prehistoric canoes in

Newnan’s Lake near Gainesville. With assistance from volunteers and stu-

dents, archaeologists recorded canoes in a two-mile stretch of the exposed

lake bed—the largest group of prehistoric canoes found to date in North

America. About 75 percent of the watercraft dated to the late Archaic or

early Woodland Periods in Florida’s history, or approximately 2,300 to 5,000

years ago. The location of the finds was named the Lake Pithlachocco Canoe

Site after an early Creek or Seminole name for Newnan’s Lake, appropriately

meaning “boat house.” Ranging in length from about 15 feet to a little over

30 feet, al of the canoes were manufactured from solid logs using fire to

char the wood and shell or stone tools to scrape the burned portions away.

Probably associated with a vil age site on the lake shore, the canoes likely

were abandoned when they became worn out, and in fact many showed

evidence of wear and damage.

Early European explorers noted the indigenous watercraft they saw, de-

scribing them as seaworthy, agile, and expertly handled. Used for fishing

and transport, the canoes carried native Florida peoples around the coast

and throughout the interior. Wooden watercraft continued to be made and

proof

used by native Floridians into the contact, exploration, and colonization

eras. Today, the native Floridian tradition of paddle-propel ed watercraft

survives. Seminoles stil living in the Everglades preserve their ancestors’

maritime skil s in canoe construction and handling. Additional y, the clear,

shallow, slow-flowing creeks of Florida’s interior draw tens of thousands of

visitors and residents to spend relaxing summer days in modern canoes.

European Contact and Colonization

On 7 June 1494, the Kingdom of Spain claimed Florida and all of the newly

discovered and as-yet-undiscovered lands of the Americas as part of the

Treaty of Tordesil as. The treaty, proposed by the pope, split the world down

a line drawn about halfway between the Cape Verde Islands and the Carib-

bean islands. The Portuguese claimed lands east of the line, which included

India and the rich spice islands of Malaysia, while the Spanish looked for-

ward to sole control of the New World on the western side of the line. The

treaty was, however, ignored by other European nations such as England,

France, and the Netherlands, setting the stage for centuries of dispute, war-

fare, and colonial competition.

392 · Del a A. Scott-Ireton and Amy M. Mitchell-Cook

Spanish explorers soon expanded from the islands of the Caribbean into

the heart of the New World. This expansion was, of course, enabled by water-

borne transport. Within a few years, the Spanish developed a regular route

between Spain and its New World colonies, called the Carrera de Indias, or

the “Indies run.” This round-trip voyage began in Spain with a convoy of

ships carrying manufactured materials, clothing, horse tack, foods, books,

and other goods that were in great demand in the colonies. After deliver-

ing the cargo to New Spain (Mexico), the ships took on spices, dyestuffs,

precious metals, and exotic and expensive products of the colonies for the

return voyage. Ideal y, the fleet made the round-trip each year, avoiding the

proof

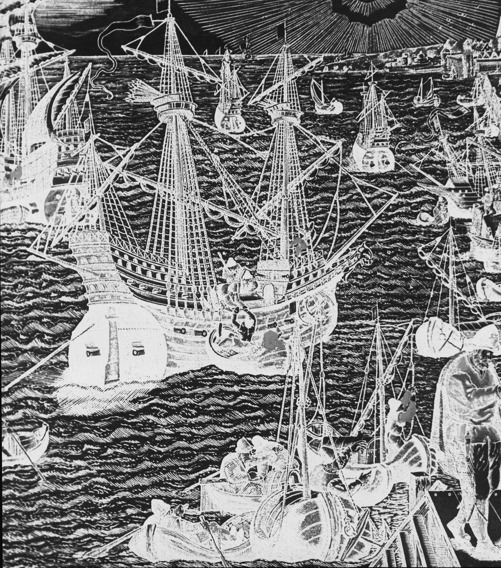

New World fleets of the sixteenth century included vessels of different types and sizes,

as shown in this 1594 engraving. Courtesy of the University Press of Florida.

The Maritime Heritage of Florida · 393

late summer and fall season in the Caribbean that often brought hurricanes

and tropical storms.

The large landform bounding the Gulf of Mexico to the east was largely

unknown to the Spanish through the first decade of the sixteenth century.

As explained in chapter 2, conquistador Juan Ponce de León general y is

credited with European discovery of La Florida

,

named in part to honor the

Easter season. Although Juan Ponce’s first colonizing mission to La Florida

proved unsuccessful, the Spanish Crown realized the need for establishing

a permanent settlement in the newfound land. Other nations, including

France and England, made uncontested forays into Spanish New World

territory because no Spanish settlements or troops were there to prevent

them. Further, a permanent settlement on the coast would provide aid to

shipwrecked sailors. During the first half of the sixteenth century, explor-

atory voyages along the Gulf coast, including Pánfilo de Narváez in 1528 and

Hernando de Soto in 1539, identified spacious harbors and sheltered bays.

One bay in particular seemed especial y well suited for a settlement, with

deep water close to shore to facilitate loading cargo, good holding ground

for anchored ships, and sheltering land to provide calm mooring. Cal ed

Ochuse or Polonza on early maps, the Spanish renamed it Bahía Filipina del

Puerto de Santa María; today the harbor is called Pensacola Bay.

proof

Don Tristán de Luna y Arel ano led a colonizing mission to Bahía Fili-

pina, which included families, slaves, Aztec mercenaries, livestock, and all

the tools, equipment, and supplies to found a Spanish city on the edge of

the empire. Leaving New Spain, Luna’s fleet of eleven ships arrived in Pen-

sacola in August 1559 with plans to clear land and construct houses for the

settlers. Only a month later, however, a powerful hurricane struck the fledg-

ling colony and sank most of the ships in the fleet and, with those losses,

any chance for a successful colony. The survivors salvaged what they could

from the wrecked ships, but, suffering from food shortages and privation,

most marched north into the interior to try to obtain food from the native

peoples. Failing to find adequate supplies, the survivors eventual y returned

to Pensacola and were evacuated back to New Spain. The Spanish did not

return to Pensacola for more than a hundred years; in the meantime, the

Spanish founded a permanent settlement in 1565 at St. Augustine on the east

coast.

After Luna’s failure on the Gulf coast of Florida, Don Pedro Menéndez de

Avilés came to the Atlantic coast to accomplish the same goals of consoli-

dating Spanish control, protecting the route of the treasure fleets, and aid-

ing shipwrecked sailors. Menéndez also had an ambitious plan to establish

394 · Del a A. Scott-Ireton and Amy M. Mitchell-Cook

mines and profitable agriculture, and, like other conquistadores, convert the

native peoples to Christianity; he also hoped to find his son, lost in an earlier

shipwreck on Florida’s coast. Establishing Spanish control was especial y

crucial in east Florida because, in 1562, a French Protestant (Huguenot) ex-

pedition under Jean Ribault explored the area around St. Augustine before

founding the settlement of Charlesfort in present-day South Carolina. A

second French incursion in 1564 landed a small garrison at Fort Caroline

on the St. Johns River, which the Spanish destroyed. Menéndez’s flagship

San

Pelayo

, along with four additional vessels, arrived off the coast on 8 Sep-

tember 1556 carrying colonists to found the first successful European town

in what is now the United States. Despite hurricanes, disease, and attacks

by English privateers, St. Augustine remains the nation’s oldest continual y

inhabited city and port. Situated on a strategic harbor and relying on ships

to bring supplies and additional settlers, St Augustine’s maritime focus was

reinforced by the construction of the Castillo de San Marcos in 1672–95.

Among the most exciting recent discoveries connected to these early

Spanish maritime ventures in Florida was the finding of two ships from

Luna’s lost fleet. The only remains known to be associated with a Spanish

colonization effort, these ships reveal information about seafaring in the

Age of Discovery and Exploration and about the process of transporting

proof

an entire culture into a wilderness. State of Florida archaeologists discov-

ered the first ship, called the Emanuel Point Ship (EPI) in 1992. Excavations

revealed clues to colonial plans including ceramic containers for food and

water, evidence of the Aztec mercenaries, butchered bones from cattle and

swine, leather shoe soles, and hundreds of olive pits. The University of West

Florida’s maritime archaeology program in 2006 discovered the second ves-

sel, Emanuel Point II (EPII), only 400 yards away from the first vessel. A

smal er ship than EPI, EPII contained an array of ceramic items, as well

as shafts for crossbow bolts and even bones from the ship’s cat that likely

perished in the wrecking.

Although Spain staked its claim to La Florida with a permanent settle-

ment at St. Augustine, its hold was tenuous at best. To strengthen the claim,

in 1698 a second colony was founded at Pensacola, located directly to the

north of the pass leading into the bay from the Gulf, on today’s Naval Air

Station Pensacola, and cal ed Presidio Santa María de Galve. Although

Santa María had little to recommend it, the area boasted dense pine and

live oak forests that provided ideal materials for ship construction and naval

stores such as pitch and resin. From the early sixteenth century, shipyards in

The Maritime Heritage of Florida · 395

the New World took advantage of virgin forests and a profusion of natural

resources to produce merchant vessels, warships, and a host of smaller wa-

tercraft. Although none of these ships survive, a few shipwrecks from this