The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (16 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

The negotiations were difficult; Attila did not intend to come to an easy peace. In the end, the western Roman party sent by Aetius saved the day. Aetius, who knew the Huns better than anyone else, had proposed terms that Attila was willing to accept. By the time the two embassies departed, Attilla had agreed to refrain from attacking either the eastern or western Roman kingdom.

10

Into this temporary peace, a new complication suddenly intruded itself.

Down in Rome, the emperor Valentinian’s sister Honoria had been living in the royal court for most of her life. In 449, she was thirty-one, and her life was growing ever more dull; she was unmarried, and although she had great privilege as the emperor’s sister, his daughters were growing up and overshadowing her. The one bright spot in her life was her steward, Eugenius, who became her lover.

11

16.1: A contemporary portrait of Attila the Hun

. Credit: Alinari/Art Resource, NY

But late in 449, her brother discovered the affair. To him, it seemed an act of treason; if Honoria married Eugenius, the pair could easily become emperor and empress, since Valentinian had no male heir. He arrested Eugenius, put him to death, and ordered his sister to marry a Roman senator named Herculanus, an older man who had a bone-deep loyalty to the emperor and could “be depended upon to resist if his wife attempted to draw him into ambitious or revolutionary schemes.”

12

Honoria was horrified. And so she sent one of her servants on the dangerous journey to Attila’s camp, along with money, a ring, and a promise: if Attila would come and rescue her, she would marry him. “A shameful thing, indeed,” sniffs Jordanes, “to get license for her passion at the cost of the public good.”

13

But Honoria wasn’t indulging her passion for Attila, who (despite his undoubted charisma) was twelve years her senior and universally described as short, squat, small-eyed, and large-nosed. She had seen a way out of her gray and pointless life. If she were to marry Attila,

he

could become emperor of Rome, and she would be empress. And even if he failed to overcome her brother, she would still become queen of the Huns.

Attila at once accepted the offer. He sent a message not to Valentinian, but to Theodosius II—the senior and more powerful of the two emperors—demanding not only Honoria for his wife, but also half of the western Roman territory as her dowry. And Theodosius wrote at once to Valentinian, suggesting that he do as Attila demanded in order to avoid an invasion of the Huns.

Valentinian was apoplectic, both at his sister’s plan and at Theodosius’s suggestion. He tortured and beheaded the servant who had carried Honoria’s message, and threatened violence to his sister as well, but his mother Placida (who had herself been married to the barbarian Ataulf) interceded and protected the princess. He also refused, flatly, to agree to Attila’s demands.

It was at this delicate moment that Theodosius II, out riding—he was passionately fond of

tzukan

, an early form of polo, and had laid out a polo ground in Constantinople—fell from his horse and died.

14

Like Valentinian II, he left no male heir; the most powerful personality in the east was his sister Pulcheria, his co-ruler and empress. Pulcheria chose a husband to help her remain empress: the soldier Marcian, who had been at Carthage when Geiseric took it from the Romans, eighteen years earlier. After swearing the required oath not to fight the Vandals any more, Marcian had been set free and had spent the next two decades rising through the ranks of the army. He had to agree, as a condition of the marriage, to maintain Pulcheria’s virginity, which he did. (She was, in any case, fifty-one.)

Their first act as rulers of the east was to defy Attila, refusing to pay him the bribes that Theodosius had been shelling out to keep the Huns from attacking Constantinople. It was a gamble; Attila might turn and attack, but on the other hand, he had just been given the perfect excuse for invading Valentinian’s domain instead.

The gamble succeeded. Attila assembled his army—the frightened residents of the western empire insisted that he had half a million men at his command—and began to march west.

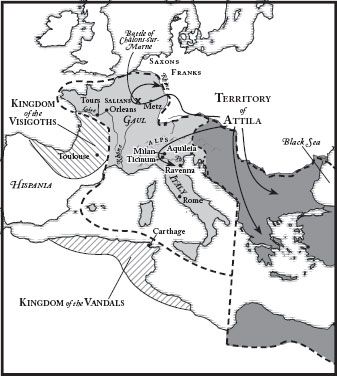

Between 450 and 455, Attila the Hun approaches Rome, Pope Leo the Great negotiates a political peace, and the Huns lose their chance at nationhood

R

ATHER THAN MARCHING

straight across the difficult Alps directly towards Ravenna, Attila led his army towards Gaul. By April, he had reached the city of Metz, right in the center of the former Roman province, and captured it for his own. “They came to the town of Metz on Easter Eve,” writes Gregory of Tours, “burned the town to the ground, slaughtered the populace with the sharp edge of their swords and killed the priests of the Lord in front of their holy altars.”

1

His territory now stretched almost from the Black Sea to the north of Italy, threatening both Roman capitals. The general Aetius, who for so long had controlled the affairs of the western empire, put together a coalition against him. The western Roman army was joined by the Visigoths of Hispania and southwestern Gaul, under their king Theodoric I, and Aetius also had a new ally: the tribe of the Salians.

The Salians were Franks, the strongest of the tribes who settled into northern Gaul as

foederati

. Now the chief of the Salians led the warriors of the entire Frankish coalition into the Roman camp to help fight against the Huns. He was one of the earliest “long-haired kings” of the Franks; the Salian chiefs wore their hair long to distinguish them from the ordinary Franks, to demonstrate their greater power.

2

The name of this chief is unknown, but later chroniclers would call him Merovech.

Aetius now had Visigoths, Franks, and Burgundians (the Germanic tribe in the Rhine valley, now in full submission to Rome) in his camp. The joint army of former barbarians and Roman soldiers marched towards the western Roman city of Orleans. In June of 451, they met the Huns in battle at Châlons-sur-Marne, halfway between Orleans and the Hun-occupied town of Metz.

Jordanes says that while the Huns put Attila and his strongest warriors in the center of their line, with the weaker and less reliable allies on each wing, Aetius and his Romans fought on one wing and Theodoric I and the Visigoths on the other, with the troops in whose loyalty they had “little confidence” in the middle, so that they could not easily flee in the midst of battle.

3

The strategy succeeded. The wings of the Hun attack disintegrated, and Attila was forced to retreat with his core of warriors back across the Rhine.

17.1: Attila’s Conquests

Gaul had been saved in an expensive victory. Over 150,000 soldiers fell in the battle; the chronicler Hydatius claims that 300,000 men died. The slaughter was so great, says Jordanes, that a brook flowing through the battlefield was swollen and “turned into a torrent by the increase of blood.”

4

Theodoric I of the Visigoths had fallen in battle; his son Thorismund led the diminished Visigoths back to Toulouse kingless. The Franks limped home, their numbers slashed.

Attila, on the other side of the Rhine, kept track of the disbanding of the coalition. When the allies were safely away, he made a second attack: this one on Italy itself.

The attack began in early 452, and the north of Italy quickly fell to the Huns. Attila’s army destroyed the city of Aquileia, sacked Milan and Ticinum, and laid waste to the countryside. Aetius’s reduced army was not strong enough to meet him in full battle again. Instead, the Romans were forced to harass the Huns in small sorties, doing their best to slow the Hun advance.

5

When Valentinian III left Ravenna with his court and went south to Rome for safety, it became clear that neither the emperor nor the

magister militum

had any chance of halting the Hun advance. So Leo the Great, bishop of Rome and the first pope of the Christian church, took matters into his own hands. He travelled north to intercede with the king of the Huns on his own. Attila agreed to see him, and the two men met at the Po river. Afterwards Leo never wrote or spoke of what had passed between them, but when the audience had ended, Attila had agreed to a peace.

To the terrified Romans (and perhaps to Aetius as well), Leo’s success must have seemed like a magic spell. The historian Prosper of Aquitaine thought that Attila was overwhelmed by Leo’s holiness; Paul the Deacon insisted that a huge supernatural warrior with a drawn sword, sort of a cross between “Mars and Saint Peter,” stood beside Leo and terrified Attila into a truce.

6

But hints of different motivations can be woven together into a less dramatic interpretation. For one thing, the Huns had lost as many warriors as their opponents; Attila’s remaining army could ravage northern Italian towns, but a siege of Rome was probably out of his power. For another, the Huns were already fairly well loaded down with loot and were no longer as dead set on collecting further riches. And for a third, they were becoming very anxious to leave Italy. The summer heat had aggravated an episode of plague, and this “heaven-sent disaster” was decimating their already thinned ranks. Leo’s approach gave Attila the chance to retreat with his dignity intact. He left Italy, still breathing fire, insisting that he would come storming back to the west if Valentinian III didn’t send him Honoria: “seeming to regret the peace, and vexed at the cessation of war,” Jordanes writes.

7

Leo returned to Rome haloed with victory. For the first time in history, a bishop had taken on the emperor’s job. Valentinian’s decree, the six-year-old imperial pronouncement that made Leo head of the entire Christian church, had given the pope an extra dimension of power. He was the spiritual head of the church, but the spirit of the church could not survive if its adherents were wiped out. As spiritual leader, he could also claim the right to guarantee the church’s physical survival.

Attila would never return to Italy. Back in his headquarters across the Danube, recovering his strength and rebuilding his army, he decided to marry. His choice was Ildico, the daughter of a Gothic chief. She was reportedly young and very beautiful, but the marriage also gave him a closer tie with the Gothic allies he needed to rebuild his weakened army. Attila was not averse to having more than one wife, but he had likely given up hope of gaining the title “Western Roman Emperor” by way of marriage with Honoria. If he wanted Rome, he was going to have to fight for it.

He celebrated the wedding with an enormous feast, at which he gave himself up “to excessive joy,” as Jordanes puts it; he probably drank an enormous amount before passing out in the bridal chamber. “As he lay on his back,” Jordanes writes, repeating the lost account of the historian Priscus, “heavy with wine and sleep, a rush of superfluous blood, which would ordinarily have flowed from his nose, streamed in deadly course down his throat and killed him.” When his attendants broke down the doors of his rooms, late the next morning, they found Attila dead in his bed and his bride weeping and covered with his blood. His officers buried him late at night, filling the grave with treasure and then (like Alaric’s followers decades earlier) executing the gravediggers so that his burial place could never be found.

8

Attila’s sons tried to pick up his mantle, but with their leader dead, the Huns began to disintegrate. Like the Visigoths before Alaric, the Huns before Attila were not a nation. They were barely even a

people

: they were still, simply, a collection of tribes with a distant past in common and a charismatic leader.

Alaric had turned his followers into Visigoths; Attila had united his tribes into a single army of Huns. But when the ambition of a single leader was the driving force behind the emergence of a new people, the death of the leader could mean the death of a newborn national identity.

The Visigoths, perhaps through long association with the Romans, had picked up enough trappings of administration and bureaucracy to hold their confederation together until a new king emerged. The Huns were not so lucky. By 455, they had been thoroughly defeated. Driven back from the Roman borders, they scattered; their chance to become a nation had passed.