The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (17 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

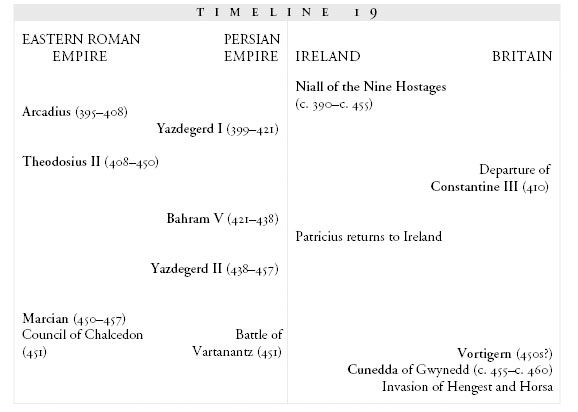

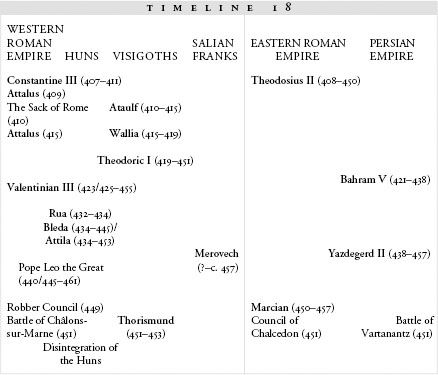

Between 451 and 454, both the eastern Roman emperor and the Persian emperor try to control belief

T

HE EASTERN HALF

of the empire had not been unconcerned with the affairs in the western half. Attila’s invasion, the rising power of the Vandal and Visigothic kingdoms, the rapid turnover in emperors: all of these had registered on the consciousness of the eastern Roman court.

Registered, but not dominated. The Roman court at Constantinople was preoccupied with its own difficulties. Nothing reveals the death of the common Roman cause like the relative prosperity and peace of the eastern Roman empire during the west’s struggle for survival.

In fact, while Aetius and his allies were fighting desperately against the Huns in Gaul, the eastern Roman emperor Marcian was presiding over a church council. He had called this council to tackle, once again, the vexed problem of how Christ’s two natures, the human and the divine, related to each other. The bishops of Rome and Alexandria were still excommunicated, the bishop of Constantinople had been declared a heretic, and Marcian hoped to straighten the situation out.

This desire was complicated by Marcian’s tendency to agree with the bishop of Rome’s theology. He wanted to support the power of the bishops in his own part of the empire, but Leo’s expression of the relationship between the two natures was much more attractive to him. In Christ, Leo had written, the human and divine natures remained distinct: “not divided in essence, but…both natures retain their own proper character without loss…. For each form does what is proper to it with the co-operation of the other; that is the Word performing what appertains to the Word, and the flesh carrying out what appertains to the flesh.”

1

It was this formulation that Marcian found closest to his own conviction, and little wonder: Leo had neatly encapsulated the double identity that lay at the core of the empire’s existence. It was the same capacity to hold two things together in one that had attracted Constantine back at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge.

But Marcian had to promote Leo’s doctrine without admitting Leo’s claim to ultimate spiritual power, something the emperor wanted to keep for his own city; Constantinople had to remain equal to Rome. So when he called the church council in 451, he refused to hold it in Italy as Leo suggested. He announced that instead it would be at the city of Chalcedon, right across the water from Constantinople. This was a little too far for Leo to come, particularly since he did not wish to leave the church of Rome leaderless during a Hun invasion; so the bishop of Rome sent several churchmen to be his representatives, along with his own written statement detailing the exact relationship of the two natures.

In Leo’s view, the council could be a short one. His delegates should read his statement, and then, “Peter having spoken, no further discussion should be allowed or required.” But under Marcian’s direction, the bishops instead agreed that the statement was in line with what they had already decided, on their own authority. They also agreed (again prompted by Marcian) that the bishop of Constantinople, while perhaps second to the bishop of Rome himself, nevertheless had more authority than any other bishop. He was not merely a bishop, but a patriarch: a churchman with authority over

other

bishops.

2

This produced a series of letters between Leo, Marcian, and the eastern bishops in which Leo complained that the east wasn’t paying enough attention to his authority and Marcian and the bishops told Leo to mind his own business, with all of this jockeying for position framed in flowery sacred language. “The See of Constantinople shall take precedence,” the bishops wrote to Leo. “We are persuaded that, with your usual care for others, you have extended that apostolic prestige which belongs to you to the church in Constantinople, by virtue of your great disinterestedness in sharing all your own good things with your spiritual kinsfolk. But your holiness’s delegates attempted vehemently to resist this decision.” “I am surprised and grieved that the peace of the universal Church which had been divinely restored is again being disturbed by a spirit of self-seeking,” Leo wrote back to Marcian. “Let the city of Constantinople have its high rank and long enjoy your rule. But secular things stand on a different basis from things divine. Anatolius [the bishop of Constantinople] cannot make it an Apostolic See.” Hedging his bets, he also wrote to Pulcheria, the emperor’s wife: “Anatolius has been inflamed with undue desires and intemperate self-seeking,” he complained. “By the blessed Apostle Peter’s authority, we do not recognize the bishops’ assent [to Constantinople’s exaltation].” And to the bishop of Constantinople himself, Leo wrote, “You went so far beyond yourself as to drag in an occasion of self-seeking. This haughty arrogance tends to the disturbance of the whole Church!”

3

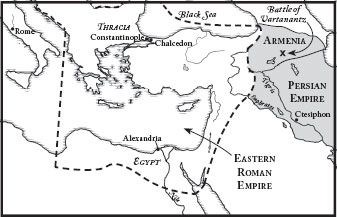

18.1: The Battle of Vartanantz

None of this was as bloody as the battles going on in Gaul between Aetius’s army and the Huns, but the issue was not all that different. It was an argument over territory, over authority, over legitimacy: a battle for a spiritual crown, but a crown nonetheless.

Leo’s protests got him nowhere; the emperor continued to insist on the prestige and independence of the bishop of Constantinople, and the Council of Chalcedon closed on that note. The eastern Roman empire had taken an additional step away from Rome.

The aftereffects of the council would ripple on through the eastern kingdom for years to come. Down in Egypt, resentment ran strong over the demotion of the bishop of Alexandria to a place below the bishop of Constantinople; the resentment continued in a strong underground current that would only grow more destructive. And now that the Council of Chalcedon had confirmed as orthodoxy that Christ’s two natures were separate but indivisible, many Christians who disagreed with this formulation began to migrate over into Persia—where they were welcomed by the Persian emperor Yazdegerd II (son of Bahram V, who had died in 438).

*

D

ESPITE HIS WILLINGNESS

to disaccommodate Marcian by accepting his refugees, Yazdegerd II was no friend of Christianity. In fact, he had not long before imposed his own sort of orthodoxy: rather than doing this through council, as Marcian had, Yazdegerd simply decreed that Zoroastrianism would be followed in all parts of his empire, including the Persian half of Armenia, which up until this point had remained Christian. The decree is recorded by the Christian Armenian historian Yegishe, who heard it with his own ears. “He alleged that we, the believers in Christ, were his opponents and enemies,” Yegishe writes, “and commanded, ‘All peoples and tongues throughout my dominions shall abandon their false religions and shall come to worship the sun.’”

4

Like Marcian, Yazdegerd II had both political and theological motivations. He was devout in his faith, but the decree was motivated more by a desire to root out any sympathy with the eastern Romans—particularly in the less reliably loyal parts of his empire. The Armenians saw the decree both as an abridgment of their freedoms (which it was) and as religious persecution, and refused to give up their Christian faith.

Yazdegerd reacted with force. In 451, the same year as the Council of Chalcedon, he marched into Armenia. Sixty-six thousand Armenians gathered behind their great general Vartan, ready to go into battle as martyrs.

In the fight that followed, the Battle of Vartanantz, Vartan was killed, and both sides suffered heavy losses: “Consciousness of defeat came to both sides,” Yegishe says, “because the piles of the fallen bodies were so thick that they looked like craggy masses of stone.”

5

Ultimately the Persians were victorious over the smaller Armenian army; Yazdegerd II imprisoned and tortured the surviving leaders and reduced Armenia to a Persian territory, putting a new governor in charge of the country. Meanwhile, Yazdegerd II took preventative measures against other possible dissidents; in 454, he began to enact a series of decrees that kept the Jews in Persia from observing the Sabbath and eventually from educating their children in Jewish schools.

6

Both emperors were still operating under the belief that one set of religious beliefs would make their empires stronger; that orthodoxy, the enforcement of a single theology and religious practice, would bind the territory together. But in both Persia and the eastern empire, the discontent was merely driven out of sight, where it spread beneath the surface like groundwater.

Between 451 and 470, Ireland falls under the domination of the Ui Neill, Patrick brings Christianity to the island, and Vortigern invites the Angles and the Saxons to Britain

P

AST THE BATTLEFIELDS

of Gaul, across the water from the growing power of the Visigoths in Hispania, far away from the western throne, the islands of Britain were piecing together their own identity.

The western island of Ireland, never occupied by Roman soldiers or crisscrossed with Roman roads, was taking its own winding path towards nationhood. Like the tribes that surrounded the Roman empire, the peoples of Ireland were a collection of tribes and clans, each boasting a certain local power and led by a warlord and his family. But even without Roman conquest, the Irish tribes were not free from Roman influence. In 451, the strongest tribe in Ireland was the Venii, or Feni, and the strongest clan of the Feni was the Connachta. The leader of the Connachta family was named Niall of the Nine Hostages, and his mother was Roman; Niall’s father, Eochaidh, had captured a Roman girl during a raid on Britannia and made her his concubine.

1

Niall, the youngest son in his family, became clan leader after his father’s death. The chronicles of Irish history, most of which come from centuries later, weave his exploits into legend and combine them with the accomplishments of other Irish kings, making it difficult to sift out exactly what Niall accomplished.

But one of the tales hints at a very bloody rise to power. According to “The Adventures of the Sons of Eochaid Mugmedon,” Eochaidh sends Niall and his four older brothers (all sons of his father’s legitimate wife, unlike Niall) on a quest to determine which one of them deserved to inherit his power. On their journey, the sons grow thirsty and go in search of water. They find a well, but a horrible hag guards it:

[E]very joint and limb of her, from the top of her head to the earth, was as black as coal. Like the tail of a wild horse was the gray bristly mane that came through the upper part of her head-crown. The green branch of an oak in bearing would be severed by the sickle of green teeth that lay in her head and reached to her ears. Dark smoky eyes she had: a nose crooked and hollow. She had a middle fibrous, spotted with pustules, diseased, and shins distorted and awry. Her ankles were thick, her shoulder blades were broad, her knees were big, and her nails were green.

2

The hag demands that the brothers trade sex for access to the well. The four older brothers refuse, but Niall throws himself enthusiastically on her, ready to sleep with her for the sake of the water. Immediately she transforms into a beautiful maiden in a royal purple cloak. “I am the Sovereignty of Erin,” she tells him, “and as you have seen me, loathsome, bestial, horrible at first and beautiful at last, so is the sovereignty; for seldom it is gained without battles and conflicts; but at last to anyone it is beautiful and goodly.”

3

In the tale, Niall’s brothers then acclaim him as family leader of their own free will. But Niall’s rise, first to power over his clan and then to the kingship of the Feni tribe, was undoubtedly accompanied with violence, forced possession, and bloodshed: bestial and horrible. Only with the crown in one hand and his sword in the other could he claim the beauty of legitimate kingship.

Over the decades of his reign, Niall expanded his power over the Feni into one of the first exercises of high kingship: control over the other minor kings of Ireland, over the other tribes. He earned the nickname “Niall of the Nine Hostages” by taking prisoners from nine of the tribes that lay around him, guaranteeing the loyalty of their tribal leaders. With Ireland more or less united under his rule, he then launched raids on the coasts of Gaul and Britain.

During one of these raids, he captured a Romanized Briton named Patricius and took him back to Ireland as a slave, where Patricius served for six years before stowing away on an Irish raiding ship and escaping into Gaul when it docked. There, he was converted to Christianity and had a vision calling him to return to the land of his slavery and teach the Irish of Christ.

This much we learn from Patricius’s own writings, his

Confessio

. By the time he arrived back at the high king’s court, Niall of the Nine Hostages had died in battle (either in Britain or in Gaul), and his own sons were battling over his kingdom. While interfamily warfare went on around him, Patricius devoted himself to the spread of Christianity, so successfully that Ireland became Christian long before the British island to the east. Later Christian historians knew him as Saint Patrick, the apostle to the Irish, and credited him with driving the snakes out of Ireland.

In fact, there had been no snakes in Ireland since the end of the Ice Age (“No reptile is found there,” writes the English church historian Bede, “for although serpents have often been brought from Britain, as soon as the ship approaches land they are affected by the scent of the air and quickly perish”), but for the Christian writer a snake was much more than a snake: Satan had taken the shape of a snake in the Garden of Eden, and serpents (which were sacred to the druids, the practitioners of the indigenous religion of Ireland) symbolized the powers of darkness that were opposed to the Gospel of Christ. The new faith was slowly supplanting the old.

4

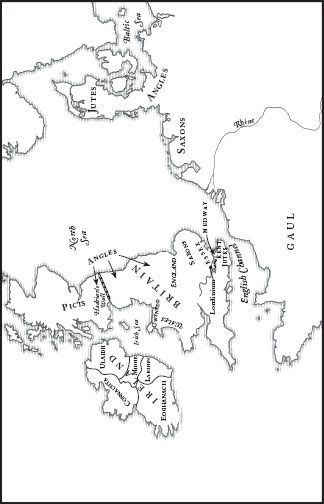

19.1: Ireland and Britain

By the time of Patricius’s death, sometime before 493, three sons of Niall held power over three kingdoms in the northern half of the island: Midhe, where the ancient city of Tara lay; Ulaidh; and Connachta, the original homeland of the clan. Their descendents would rule as the Ui Neill dynasty for six hundred years, but their influence would stretch far, far beyond the Middle Ages. Niall’s particular Y chromosome shows up in as many as three million men worldwide; his sons and their randy offspring managed to sire so many children that one in twelve Irishmen (one in five in the part of Ireland that was once Connachta) can claim Niall of the Nine Hostages as their ancestor.

5

Despite their dominance, the Ui Neill did not conquer the whole island. In the southwest of Ireland, the clan of the Eoghanach still ruled, resisting the spread of Feni power. To the southeast, the Laighin tribe held onto its land as well. But some of the Laighin left, in the face of ongoing attack from Niall’s descendents, and settled on the coast of Britain, in the area that became Wales. There, in flight from the high king of Ireland, they came into direct conflict with the high king of Britain.

6

This high king was, so far as we can tell, a man named Vortigern, who by 455 had the unenviable task of defending Britain from invaders determined to take the island for their own. Roman Britain, more or less abandoned by its occupiers after the departure of Constantine III in 410, was now a collection of local warlords—mostly Romanized Celt or Celticized Roman—along with a few Saxon settlements which the Romans had allowed along the coast. Raids from Irish pirates, the Scoti, had grown more vicious under the dominance of the Ui Neill: in the vivid words of the sixth-century historian Gildas, the Irish raiders emerged from their ships “like dark throngs of worms who wriggle out of narrow fissures in the rock when the sun is high and the weather grows warm.” The northern Picts, meanwhile, were launching ever more vicious attacks down across Hadrian’s Wall, aiming to grab the north for their own.

7

In the face of all this chaos, the minor kings and tribal chiefs of Britain gathered together in council, in which they elected the northern king Vortigern as their warleader. Vortigern sent one of those chiefs, a British warlord named Cunedda, to drive the Laighin out of their new home; Cunedda, his eight sons, and his soldiers did so and founded a kingdom of their own, Gwynedd, in the conquered land.

Vortigern also sent a letter to the Roman

magister militum

Aetius, begging for help against the Picts. But it went unanswered.

In desperation, Vortigern suggested that the remaining British soldiers bolster their ranks with Saxon allies; the British could allow more Saxon settlements in the south (particularly in Essex and in Kent, on the southeastern coast) in exchange for tribute warriors who would help them to fight against the Picts and the Irish. The other chiefs agreed, and so Vortigern sent messages not only to the Saxons on the distant North Sea coast just west of modern Denmark, but also to their allies the Angles, who lived just northeast of the Saxons, on the dividing line between modern Germany and Denmark. This strategy, undertaken in desperation, earned him the hatred of later historians: “They devised for our land,” froths Gildas, “that the ferocious Saxons (name not to be spoken!), hated by man and God, should be let into the island like wolves into the fold, to beat back the peoples of the north…. How utter the blindness of their minds! How desperate and crass the stupidity!”

8

But at first the strategy seemed to be working. The Angles and the Saxons accepted the invitation, and around 445 they sailed across the water to join the British in their fight against the Picts. “They fought against the enemy who attacked from the north,” Bede writes, “and the Saxons won the victory.” In return, Vortigern granted the allies settlement rights in Kent; or, as the inexorably hostile Gildas puts it, the newcomers “fixed their dreadful claws on the east side of the island, ostensibly to fight for our country, in fact to fight against it.”

9

The Saxons and Angles, once established in the green land of Kent, did not stay nicely in the granted land; they had ambitions to spread farther. In a matter of months, new shiploads of their countrymen (along with the Jutes, allies of the Angles who lived on the Danish peninsula just north of them) were arriving on the southeastern shores in longships. “They were full of armed warriors,” the British historian Geoffrey of Monmouth says, “men of huge stature.” Vortigern had crushed the northern menace, and in doing so had created a southern invasion.

10

Led by two Saxon brothers named Hengest and Horsa, the Jutes occupied the southern coast, the Saxons moved from Kent farther inland, to the south and southwest of Londinium, and the Angles invaded the southeastern coast just above the Thames. Destruction reigned. “All the major towns were laid low,” Gildas mourns. “In the middle of the squares the foundation-stones of high walls and towns that had been torn from their lofty base, holy altars, fragments of corpses, covered (as it were) with a purple crust of congealed blood, looked as though they had been mixed up in some general wine press. There was no burial to be had except in the ruins of houses or the bellies of beasts and birds.”

11

The British tribes, allied behind Vortigern, spent six years fighting fruitlessly against this overwhelming influx. The invaders seemed unstoppable, so fierce that the monk Nennius, writing his

History of the Britons

several centuries later, ascribes magical malice to them. Vortigern, he insists, was unable to build a fortress that would withstand them until his court magicians told him that he would need to find a child born without a father, sacrifice him, and sprinkle his blood over the foundations.

This echo of a druidic ritual suggests that the British were driven to drastic and ancient strategies in desperate defense of their country. But Nennius, a Christian priest constructing a Christian history, adds that the sacrifice never actually happened. Instead, the child, once discovered, showed Vortigern a pool beneath his proposed foundations in which two serpents, one white and one red, slept. “The red serpent is your dragon,” he told Vortigern, “but the white serpent is the dragon of the people who occupy Britain from sea to sea; at length, however, our people shall rise and drive away the Saxon race from beyond the sea.”

12

This after-the-fact prophecy was not entirely fulfilled. In 455, Vortigern finally managed to defeat the invaders in a pitched battle at the fords of the Medway river, in Kent. The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

says that Horsa was killed in the fighting. The loss of one of their chiefs forced the invaders to regroup, and for a few brief moments Vortigern must have had wild hopes of victory. But Horsa’s son took up his father’s mantle, and the balance tipped back. For the next fifteen years, war continued, each year seeing a new and violent conflict between Vortigern, his men, and the newcomers, neither side gaining the advantage, neither willing to come to terms.

13