The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (34 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

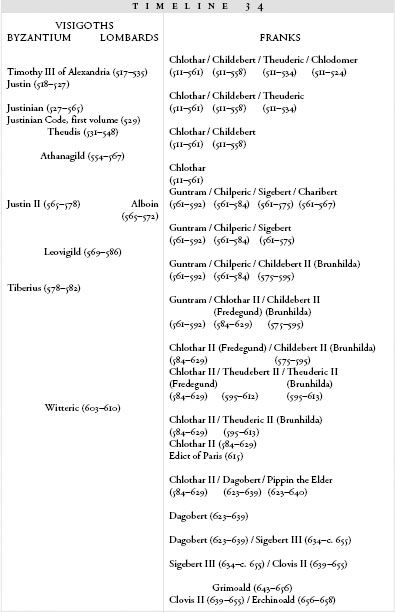

Probably this had been part of the deal made by the mayors Warnachar and Rado: they wanted him in, but not at the expense of their own power. Chlothar’s invasion got rid of Brunhilda and confirmed the authority of the mayors of the palace: each now had more authority than under the previous rulers. This authority grew even more entrenched when Chlothar agreed, two years later, to make the mayor of the palace a lifetime appointment.

Now the mayors not only were relatively independent but also could not be removed from office. Chlothar had made a devil’s deal. He had the crown of the Franks, but two-thirds of his country was ruled by the mayors—whom he could not get rid of by legal means, who had the authority to legislate for their own realms, and who were now able to act independently of the pesky royal children and aunts who had once controlled them.

T

HE

617

DECREE

that gave the mayors power for life began a slow transformation of the mayors into rulers—a transformation that would leave the Merovingian kings of the Franks without much of importance to do.

For several decades, the kingdom of the Franks had had three mayors: one each in the palaces at Austrasia, Neustria, and Burgundy. Chlothar’s confirmation of this arrangement had been an attempt to combine the fiercely local nature of Frankish politics with the existence of a high king.

But it was not entirely successful. Even with an independent mayor of the palace, the nobles of Austrasia agitated for more independence—particularly from Neustria. Perhaps ancient tribal differences, or obscure clan hostilities, lay behind the division, but the eastern and western halves of the Frankish kingdom were increasingly likely to insist on the separation of their interests. The western Franks called their land

Francia

, and referred to the eastern half as the “East Land,” or

Austrasia

. In return, the Austrasians refused to yield the title

Francia

to the west; they insisted on using

Neustria

, or “New West Land,” for their counterparts on the other side of the Frankish kingdom.

Shortly after 617, Chlothar agreed to make his twenty-year-old son, Dagobert, ruler of Austrasia, thus giving the Austrasians not only an independent mayor but an independent king. This provided the Austrasians with their desired separation from Neustria and Burgundy, although the independence of Dagobert’s rule was doubly illusory—he was firmly under his father’s thumb, and in any case the real authority in his court was held by his mayor of the palace, one Pippin the Elder.

When Chlothar died in 629, after a forty-five-year reign, Dagobert got the chance to exercise some real power. His younger half-brother Charibert tried to claim the throne of Neustria, but Dagobert first threatened him into withdrawing to the small territory known as Aquitaine, and then supervised his assassination and claimed the whole kingdom for himself.

12

Now the entire Frankish realm was under one king again, and again the nobles of Austrasia objected. Dagobert, who had once helped to preserve their independence, had become their problem.

Dagobert was forced to follow his father’s strategy; he made his own three-year-old son, Sigebert III, king of Austrasia, and once again the mayor of the palace held the real power in the Austrasian realm. The Franks were trying to balance, awkwardly, the power of the king, the rights of a royal family, and the intense desire of the Frankish noblemen (the previous clan chiefs) to rule themselves, and the rule of an infant king under the power of a local mayor of the palace was a workable if unstable solution.

Dagobert died in 639 and the kingdom remained divided: Sigebert III and his mayor of the palace kept control of Austrasia, and Dagobert’s younger son, Clovis II, was crowned king of Neustria and Burgundy, which he ruled with the substantial help of two mayors of the palace, one for each realm.

During all of these deaths and coronations, what really mattered was the power of the local mayor in each realm, not which royal son occupied the throne. But even though the post had been designed to preserve independent government in the three realms of the Franks, the mayors were not opposed to consolidating their own power. By 643, when Pippin the Elder died in Austrasia, he had also seized the mayoralties of Burgundy and Neustria.

13

Not only that: he passed them on to his son Grimoald. The mayors of the palace had not previously been able to inherit their power; they were appointed by the king. But now the mayors were adopting the royal custom of blood succession.

Grimoald now convinced the young king of Austrasia, Sigebert III, to adopt Grimoald’s own son as his heir. This would have catapulted the mayoralty into the throne room—but unfortunately for Grimoald’s ambitions, Sigebert III soon fathered a son of his own.

Grimoald refused to be defeated. In 656, after Sigebert III died at an unexpectedly early age, Grimoald mounted a coup and took the throne. He ordered Sigebert’s six-year-old heir, Dagobert II, to be tonsured (the top of his head shaved to indicate his intentions to become a priest—a sacred version of mutilation, rendering the user unfit for rule by dedicating him to the service of God) and sent him off to a monastery in England. Then he placed his own son, Childebert the Adopted, on the throne of Austrasia.

At this, Clovis II, king of Neustria and Burgundy, authorized an invasion. Clovis’s army captured both Grimoald and his son Childebert the Adopted. Both were put to death, and the throne of Austrasia was empty.

Rather than bringing the tonsured rightful king (his nephew) back from England, Clovis II allowed his official Erchinoald to declare him king of the entire realm; Erchinoald also became mayor of the palace for all three palaces simultaneously. The mayors of the Franks, intended to preserve local authority, were themselves becoming a threat to it.

14

Clovis II ruled as king of all of the Franks for barely a year before he died. He left three very small sons behind; two of them were duly coronated as kings of Austrasia and Neustria, while the third was raised in a monastery. But for the next fifteen years, the two young kings did almost nothing, while various mayors of the palaces battled for power. Later chroniclers would call these rulers the first of the

rois faineants

, the “do-nothing kings,” and the name clung to the last generations of Merovingian rule.

15

Between 572 and 604, the pope negotiates with the Lombards and sends Christian missionaries to Britain

I

N

I

TALY, CURRENTS OF

personal hatred were also shaping the Lombard kingship.

The Lombard king Alboin had folded the Gepids into his realm by force, killing their king and marrying the king’s daughter Rosemund. At a drunken banquet in 572, Alboin handed her the goblet made from her father’s skull and, in the words of Paul the Deacon, “invited her to drink merrily with her father.” Rosemund’s simmering hatred boiled over. She blackmailed a court official into assassinating Alboin while the Lombard king slept, first taking the precaution of binding his sword “tightly to the head of the bed” Alboin apparently slept with his weapon.

Alboin woke up when the assassin entered his room and tried to defend himself with the only furniture in the room, a wooden footstool, but he was killed. Rosemund and her accomplice fled to Ravenna, where the exarch welcomed them, hoping to use them against the Lombards. But the two fugitives poisoned each other, not long after arriving in Byzantine territory, and both died on the same day.

1

The essentially Germanic nature of the Lombards now reasserted itself. Alboin had been less a king than a warrior-chief; for almost his entire reign, the Lombards had been at war and on the move. After his death, they did without a king for a time. Warleaders took control of the army and conquered a series of cities, each warlord establishing his own little kingdom in the Lombard-controlled land. More than thirty of these little kingdoms, later known as duchies, stood side by side, in a period known as the Rule of the Dukes.

In 584, the Lombard dukes decided that their separate kingdoms would benefit from a shared defense. They elected one of their own, the duke Authari, to oversee Lombard resistance to any invasion. After Authari’s death in 590, they chose another man for the same purpose: Agilulf, who was “raised to the sovereignty by all” at Milan, hoisted up on a shield in the ancient ceremony that gave him a power he was not born to.

2

Two of the dukes declined to recognize Agilulf’s overlordship. Both were in the south of Italy, cut off from the main Lombard kingdom by the narrow strip of land still claimed by the emperor of Constantinople. After a few clashes of arms, as Lombard armies trooped back and forth across the Byzantine land, Agilulf forced both to acknowledge him. After this, the two Lombard kingdoms in the south were known as the Duchy of Spoleto and the Duchy of Benevento; they would continue to act as small independent kingdoms, despite their allegiance to the Lombard overlord.

In the same year as Agilulf’s election, Pope Pelagius II died, and the churchmen of Rome chose a successor. They offered the seat of St. Peter to a monk named Gregory, who did not particularly want it. Gregory had been sent to Constantinople twelve years earlier, on a diplomatic mission for the pope, and had returned from the city to his monastery with great relief. He preferred the abbey to the throne room.

3

But by the time Pelagius died, Rome was in sore straits. The Lombards had cut the city off from Ravenna and from Constantinople, the plague made a sweep through the city, and the Tiber flooded so severely that “its waters flowed in over the walls of the city and filled great regions in it.” The priests of Rome were unanimous: Gregory, who had now risen to be the abbot of his monastery, was competent, experienced, and knew how to handle relations with Constantinople. They wanted him to be the next pope.

4

Gregory, dismayed, sent a letter begging the emperor at Constantinople not to confirm the appointment, but the chief official of Rome stole the letter and instead forged another, begging the emperor to make the appointment official as soon as possible. The emperor did so, and Gregory found himself, against his will, raised on the spiritual shield of his fellow churchmen.

5

He took control of the church in Rome, shouldering his burden against his own inclinations. As pope he was supposed to be the spiritual authority in the city, but since the civil authority of Rome was cut off from easy consultation with its superiors (and since Gregory theoretically had continual communication with God, who was unrestricted by Lombard armies), he found that not only the priests, but also the prefects and officials of Rome, turned to him for guidance. “I am now detained in the city of Rome,” he wrote to a colleague, “tied by the chains of this dignity.”

6

35.1: The Lombard Duchies

Gregory was a problem-solver, a coper. It was not in his nature to turn away appeals for help, but rather to figure out a way to deal with them. The most pressing problems were earthly, not spiritual; the Lombard leader Agilulf was moving south towards Rome, anxious to take it from Byzantine control, and the dukes of Spoleto and Benevento were moving west to complete the pincer move. By 593, the Lombard armies were at the walls of Rome.

Gregory sent messages to Constantinople, warning the emperor of his peril and begging for help. Tiberius had died in 582, leaving the crown to his hand-chosen successor, his son-in-law Maurice; but the emperor Maurice was dealing with Avar invasions in the northwest and Persian complications to the east.

No imperial troops arrived. Neither did any pay for the soldiers remaining in the city; Gregory was on his own.

He took matters into his own hands. He paid the troops at Rome out of church funds (“As at Ravenna, the emperor has a paymaster for the First Army of Italy,” he wrote to Constantinople, bitterly, “so at Rome for such purposes am I paymaster”) and went out to negotiate with Agilulf on his own authority. He agreed to pay the Lombard king five hundred pounds of gold, also from the church treasury, and Agilulf withdrew.

7

Gregory had saved Rome, a feat that even more than his spiritual accomplishments earned him the nickname “Gregory the Great.” But the exarch at Ravenna—who was, theoretically, in charge of Byzantine lands in Italy—complained to the emperor Maurice that Gregory had overstepped his authority. Gregory defended his actions: he had no other choice. Furthermore, he wrote, Agilulf was not unreasonable. He would be willing to come to a general peace with all Byzantine territories, if only the exarch would agree: “For he complains that many acts of violence were committed in his regions,” he wrote to Ravenna, “and if reasonable grounds for arbitration should be found, he also himself promises to make satisfaction in all ways, if any wrong was committed on his side…. It is no doubt reasonable to agree to what he asks.”

8

But the exarch refused. His pride had been injured, and a standoff with the Lombards lasted until he died in 596 and was replaced by a more reasonable man. The new exarch, Callinicus, agreed to sign a treaty with Agilulf. For a time, peace between the Lombards and the Byzantine territories resulted.

9

Pope Gregory was finally able to turn away from political matters and spend time on his spiritual responsibilities. His commentary on Ezekiel had been interrupted by the Lombard crisis; now he could go back to writing. And he could also attend to another duty: sending a priest over the water to Britain, to take orthodox Christianity to the peoples there.

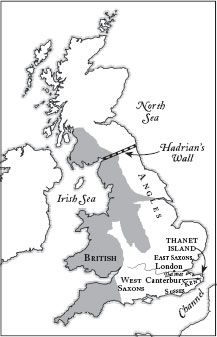

There had been Christians in Britain before. The Romans of the late empire had been Christian at least in name, and a few churches had been built. But since the collapse of Roman rule, there had been no organized Christian presence on the island. Churches in the south and east had crumbled as the unconverted Saxons had pushed in; the British churches that remained, mostly in the north and west, had been separated from the mother church at Rome for over a century.

10

Gregory took it upon himself to bring the island back into the kingdom of God, which meant evangelizing the Saxons. At the end of the sixth century, Saxons ruled along the eastern coast and in much of the southeast. The descendents of the general Aelle still ruled in Sussex, the kingdom of the South Saxons; another royal line had established itself in the kingdom for the West Saxons; the descendents of Hengest, leader of one of the original Saxon strike forces, ruled the southern kingdom of Kent; and small kingdoms ruled by Saxons and Angles bracketed the remaining British kingdoms, which still held the west and north of the island.

To bring all of these Saxons into the Christian fold, Gregory chose a monk named Augustine who had served at Gregory’s former monastery. Augustine started out with a large band of companions and plenty of supplies, got as far as the coast of the Frankish kingdom, and wilted (“seized with craven terror,” Bede says). In August of 596, he returned to Rome and asked for permission to abandon the trip. Gregory refused to relinquish the mission. He sent Augustine back to his stalled party with a letter of exhortation: “Let neither the toil of the journey nor the tongues of evil-speaking men deter you,” he wrote to them. “May Almighty God grant to me to see the fruit of your labour in the eternal country; that so, even though I cannot labour with you, I may be found together with you in the joy of the reward; for in truth I desire to labour.” Still trapped in Rome, carrying out his administrative duties with dogged faithfulness, Gregory longed for the heady fulfillment of the mission field.

11

35.2: Saxon Kingdoms

Augustine’s party took heart, crossed the channel, and in early 597 landed on Thanet Island, a tiny isle just off the coast of Kent that fell under the rule of Kent’s king, Ethelbert.

12

Probably Augustine had targeted Ethelbert from the beginning; his wife, Bertha, granddaughter of the Frankish king Chlothar I, was already a Christian.

13

When Ethelbert heard of the party’s arrival, he sent a message telling the missionaries to stay put on the island until he could decide what to do with them. Finally he decided to go and see them, rather than inviting them into his kingdom: he was suspicious, not knowing whether this was a political or spiritual mission. Talking to them, he was reassured and decided that they were harmless. Even Bede, anxious as he is to show the triumph of Christianity, can’t make Ethelbert’s reaction a dramatic one: after listening to Augustine, the king said, “I cannot forsake the beliefs I have observed, along with the whole English nation, but I will not harm you; and I do not forbid you to preach and convert as many as you can.”

14

Eventually Ethelbert did agree to be baptized, and in Christmas of 597, Gregory wrote to the bishop of Alexandria of the mission’s success. “For while the nation of the Angli, placed in a corner of the world, remained up to this time misbelieving in the worship of stocks and stones,” he exults, “a monk of my monastery…proceeded…to the end of the world to the aforesaid nation; and already letters having reached us telling us of his safety and his work…. [M]ore than ten thousand Angli are reported to have been baptized.” More priests were sent in 601. Ethelbert turned over a wrecked sanctuary in Canterbury to Augustine, to act as his headquarters, and Gregory consecrated Augustine as the bishop of the Angles at Canterbury.

15

Gregory’s epistles preserve the questions that Augustine sent back to him. Should the monks from Rome, trained and longtime Christians, actually

live

with the converts? The question suggests that the Roman mission had a low opinion of the Saxon people, an attitude Gregory at once condemned. He wrote back, “You ought not to live apart from your [new] clergy in the church of the Angli, which by the guidance of God has lately been brought to the faith…. Institute that manner of life which in the beginning of the infant Church was that of our Fathers, among whom none said that any of the things which he possessed was his own, but they had all things common.” The Saxons were converts, which meant that in Gregory’s eyes they had become one with the believers in Rome, part of the common Christian cause.

16

The common cause spread slowly. Ethelbert was not Clovis; he did not require his subjects to convert or sponsor any mass baptisms. However, Bede says that he showed “greater favor” and “affection” to those who did—so that, inevitably, the politically ambitious in the higher classes of society tended to convert. Ethelbert’s nephew, king of the East Saxons, accepted Christianity in 604, and the faith began to ripple out into Saxon society. The crimson tide of the cross had begun its slow advance across the island.

17