Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

The History of White People (21 page)

R

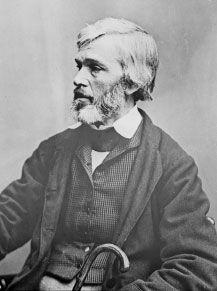

alph Waldo Emerson (1803–82) towers over his age as the embodiment of the American renaissance, but not, though he also should, as the philosopher king of American white race theory. Widely hailed for his intellectual strength and prodigious output, Emerson wrote the earliest full-length statement of the ideology later termed Anglo-Saxonist, synthesizing all the salient nineteenth-and early twentieth-century concepts of American whiteness. (See figure 10.1, Ralph Waldo Emerson.)

A quintessential New Englander born in Boston, Emerson descended from a family of scholarly ministers whose American roots reached back to 1635. Emerson’s esteemed father, the Reverend William Emerson, had delivered a Phi Beta Kappa address at Harvard—just as his son would a generation later—and served as pastor at Boston’s First Church. Such a lofty perch, while conferring eminent respectability, did not guarantee financial security even while the Reverend William Emerson lived. His death, when Waldo was not quite eight years old, plunged the family into outright hardship. Luckily Waldo’s diminutive aunt—she stood four feet three inches tall—Mary Moody Emerson (1774–1863) was there to fill a crucial gap in his education at home.

*

An 1814 American edition of de Staël’s

On Germany

had introduced German romanticism and the wisdom of India to intellectual Americans like Mary Moody Emerson. She kept the book at hand throughout her life and used it to transmit her enthusiasm for de Staël and German romanticism to her nephew before, during, and after his formal studies.

1

He had a good, traditional New England education, attending the Boston Latin School, then following his forebears to Harvard College, where he waited on tables to cover tuition. He taught school for four years before enrolling in the Harvard Divinity School, which he left as a Unitarian minister in 1829. That same year he married Ellen Louisa Tucker and became minister of Boston’s Second Church.

E

MERSON’S FASCINATION

with German thought was practically foreordained. At Harvard he studied with the confirmed romanticists George Ticknor and Edward Everett, two young scholars recently returned from studies at Göttingen’s Georg-August University. Well schooled by Aunt Mary, Emerson had incorporated her comments into his Harvard senior essay, winning second prize in 1821. Even his older brother, William, pitched in, going abroad to study at Göttingen in 1824–25 and writing home to Waldo urging him “to learn German as fast as you can” in order to follow him to Germany.

2

Fig. 10.1. Ralph Waldo Emerson

carte-de-visite.

German thought filled the air around Boston’s young intellectuals. In the 1820s Emerson read English writers like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who had studied at Göttingen with Blumenbach,

3

and William Wordsworth, both necessary guides into things German since Emerson never gained great competence in the German language. All in all, his Harvard study, Aunt Mary Moody Emerson’s keenness for German romanticism, and Germaine de Staël’s

On Germany

propelled Emerson ever deeper into study of German philosophy and literature.

T

RANSCENDENTALISM, THE

American version of German romanticism (à la Kant, Fichte, Goethe, and the Schlegel brothers), flourished in New England, particularly in eastern Massachusetts, from the mid-1830s into the 1840s. German transcendentalism offered an odd mixture, including even a hefty dose of Indian mysticism inspired by Friedrich von Schlegel, which Mary Emerson had also found congenial.

*

In place of established Christian religion (particularly the then prevailing Unitarianism), transcendentalism offered a set of romantic notions about nature, intuition, genius, individualism, the workings of the Spirit, and, especially, the character of religious conviction. At bottom, it prized intuition over study and emphasized the idea of an indwelling god who unified all creation. Guided by Aunt Mary, Emerson borrowed transcendentalism’s focus on nature as a spiritual force for his essay

Nature

(1836), now considered the transcendentalists’ manifesto.

4

†

Most leading New England transcendentalists had attended Harvard College, and many had continued into Harvard’s Divinity School preparing for the Unitarian ministry. Emerson fits the mold perfectly in several ways, as a minister and as one who resigned his pulpit after a crisis of faith. Even after leaving the ministry, however, Emerson remained intrigued throughout his life by the religious dimension of transcendentalism. In

Nature

he announces American transcendentalism as a new way of conceiving spirituality, amplified two years later in his classic

Divinity School Address

.

*

W

ITHIN THIS

German-driven transcendental swirl, one man, an Englishman, stood tallest: he was Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881). (See figure 10.2, Thomas Carlyle.) A reedy, stooped six-footer and a lifelong hypochondriac, Carlyle was usually half sick with a cold. The twenty-four-year-old Emerson (also tall, thin, and hypochondriac) discovered Carlyle’s unsigned reviews in the

Edinburgh Review

and the

Foreign Review

in 1827 and began to hail the British author as his “Germanick new-light writer,” as well as “perhaps now the best Thinker of the Saxon race.”

5

Clearly Carlyle’s take on German mysticism would lay the foundation for American transcendentalism.

Actually, Carlyle was, geographically speaking, just barely a “Thinker of the Saxon race,” having been born in Scotland in the little town of Ecclefechan, eight miles from the English border.

†

This provenance counted heavily for Carlyle, who wished to be known as a

southern

Scot, that is, as a Saxon rather than a Celt—the northern Scots, to his mind being the latter and therefore, as we have seen in this mind-set, inferior.

After study at the University of Edinburgh, Carlyle, like many other English speakers, encountered German thought in de Staël’s

On Germany

in 1817. So impressed was he that he sent his future wife, Jane Welsh, a copy of de Staël’s novel

Delphine.

Furthermore, what he saw in

On Germany

—with its racial introduction, its elevation of Goethe to mythic status, and its concluding section on German transcendental mysticism—encouraged Carlyle to study German. This enthusiasm for the German language and its literature gained him employment as a German tutor in Scotland and motivated his translation of Goethe’s

Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship

in 1824, which he sent along to Goethe in Weimar. That opening inaugurated a respectful correspondence lasting until Goethe’s death in 1832.

6

Carlyle actually came to think of Goethe as “a kind of spiritual father,” and took upon himself the task of spreading the transcendental gospel.

7

And spread it he did, writing the magazine articles Emerson was reading in New England in the late 1820s and early 1830s, many of them reviews of German authors and essays on German thought.

8

Like Carlyle, Emerson worshipped Goethe throughout his scholarly life. So thorough was this adoration that Goethe’s

Italienische Reise

shaped Emerson’s European itinerary of 1833, dictating a first stop in Rome.

9

Emerson even began collecting Goethe statuettes and portraits and named the Emerson family cat “Goethe.”

10

Emerson was thirty when he first saw Europe. By then he had left his pastorate and lost his beloved young wife to tuberculosis two years after their marriage. Now he poured energy into seeing for himself the luminaries of this new philosophy. Coleridge and Wordsworth came first, and both disappointed Emerson greatly. He found Coleridge “a short, thick old man [who] took snuff freely, which presently soiled his cravat and neat black suit.” Even worse was Wordsworth who abused the beloved Goethe and Carlyle and nattered on as though reading aloud from his books. Wordsworth later sneered at Emerson as well, calling him “a pest of the English tongue” and lumping him with Carlyle as philosophers “who have taken a language which they suppose to be English for their vehicle…and it is a pity that the weakness of our age has not left them exclusively to the appropriate reward, mutual admiration.” Emerson felt he had spent an hour with a parrot.

11

Fig. 10.2. Thomas Carlyle.

The visit in Scotland with Carlyle, however, went perfectly. Much younger than Coleridge and Wordsworth, Carlyle captivated Emerson through a day and a night of passionate exchange chock full of fresh ideas expressed energetically. At this point neither man had published canonical work, but recognizing kindred spirits, they fell into each other’s arms, initiating a lifelong correspondence that even weathered ideological strains over slavery and the American Civil War. Mutual support immensely enhanced both their careers.

At the time of Emerson’s visit, Carlyle’s novel

Sartor Resartus

had reached the public only in magazine form, and little wonder, for this ponderous, autobiographical tale drags English readers through a morass of German transcendentalism and the mysticism of Immanuel Kant, with nothing of de Staël’s clarity. Carlyle’s novel is clotted with German, making it a hard sell in Britain; its protagonist, for instance, bears the challenging name Diogenes Teufelsdröckh. While a later admirer would pronounce

Sartor Resartus

part of a “great spiritual awakening of the Teutonic race,” at the time, only two readers that we know of lauded its magazine publication: a Father O’Shea of Cork, Ireland, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

12

*

In fact, without Emerson’s tireless promotion, Carlyle’s writing career might have ended there. But Emerson took Carlyle’s novel in hand, shepherding an American edition into print and contributing a preface. With this help, the thumping, clamorous, and obscure style of

Sartor Resartus

electrified the Americans becoming known as transcendentalists: Theodore Parker spoke admiringly of a “German epidemic,” and William Ellery Channing experienced it as a “quickener” of his own ideas.

13

Thanks to Emerson, an American edition of Carlyle’s

French Revolution

soon followed. The first money—£50—that Carlyle ever earned through his writing came from Emerson, acting as Carlyle’s agent in the United States over the course of several years.

14

Indeed, Emerson made Carlyle more popular by far in America than he had ever been in Great Britain. Carlyle returned the favor, launching Emerson’s career in the United Kingdom with the 1841 publication of

Essays

. Carlyle’s advocacy had a number of English critics calling Emerson a Yankee genius, a sterling compliment since “genius” offered the romantics’ highest form of praise.

Given Emerson’s inability to read German very well, Carlyle stepped in as his teacher of transcendentalism, and not always an uncritical one. Early in their friendship Carlyle recognized the derivative nature of Emerson’s thought, explaining later “that Emerson had, in the first instance, taken his system out of ‘Sartor’ and other of [Carlyle’s] writings, but he worked it out in a way of his own.”

15

Before meeting Emerson, the prominent English academic Henry Crabb Robinson, a founder of University College, London, had dismissed him as “a Yankee writer who has been puffed by [Carlyle] into English notoriety” but who was “a bad imitator of Carlyle who himself imitates Coleridge ill, who is a general imitator of the Germans.” (Once they met, Robinson’s view of Emerson softened.) John Ruskin’s estimation of Emerson wavered over time; at one point Ruskin, one of England’s leading intellectuals, considered Emerson “only a sort of cobweb over Carlyle.”

16