The Hit-Away Kid (2 page)

Authors: Matt Christopher

“Hit the dirt! Hit it!” cried Bus, standing beside the plate with a bat in his hand.

Barry’s cap had already blown off halfway down the basepath, and he was puffing like a steam engine as he raced for home,

where Brian Feinberg was waiting for the throw-in from first base. Barry hit the dirt just as Brian caught the ball. Barry

tried to slide around him, but Brian had the plate covered like an umbrella.

“Out!” yelled the ump.

Barry sat there a minute, looking up at the ump, then at Brian, and finally toward first base, where Monk was poking a fist

into the air in triumph.

“Nice play, Monk!” a Junk Shop fan yelled.

Monk got T.V. out, then threw me out, Barry realized. It sure

was

a good play.

He rose to his feet, brushed the dust off his white uniform, and ran to get his glove and cap off the roof of the dugout.

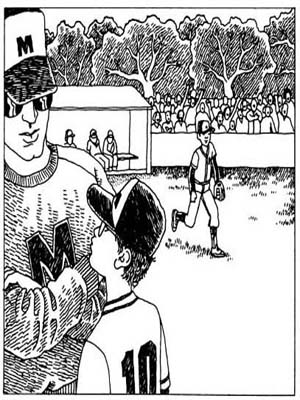

As he headed for third base, he almost collided with Coach Parker.

“Hold it, speedy,” the coach snapped.

Barry froze. That voice meant business.

“Don’t tell me that you didn’t hear me yell at you to wait on third,” the coach said firmly. “I yelled it loud enough for

the whole crowd to hear me.”

“Yes, I heard you,” Barry admitted, glancing briefly at the coach. His dark, angry eyes sent shivers through him. “I’m sorry.

I … I thought I had a good enough lead.”

“You

thought.

Listen, you’re no different from the other players, Barry. You play by the same rules as everybody else. So let me do most

of the thinking here, okay?”

Barry nodded, embarrassed. Lowering his eyes, he started to trot out to left field.

“Hold it,” the coach said. “After all that running, you need to sit for a while.” He glanced toward the dugout. “Tootsie!

Take left!” the coach ordered.

A short, stout kid sitting near the middle of the dugout cried, “Yippee!” Then, pulling a glove onto his left hand and tugging

at his cap with his right, he ran to the outfield. He flashed a smile as he passed by Barry, but Barry didn’t see it. He was

heading, head bowed, toward the dugout.

“Jack, take short.” He heard the coach snap another order.

Jack Livingston, a tall, thin redhead, ran out to replace Bus at shortstop. All at once Barry didn’t feel so bad. The coach

was putting in other substitutes, too.

Barry could still hear the coach’s strong words ringing in his ears. He sure knows how to drill them into a guy, he thought.

But was the coach 100 percent right? I

almost

scored, Barry said to himself. I wonder what the coach would’ve said if I’d been safe? He probably would have clapped like

crazy.

“You play by the same rules as everybody

else,”

the coach had said. Barry remembered the fly ball he had dropped and retrieved in time to fool everybody. Well, almost everybody.

Why did Susan have to be sitting in that particular spot on the sideline, anyway? Now he’d think about that play every time

he saw her. And he saw her a lot.

“Hey, man, can’t wait till we play you guys next week.” A strong, husky voice broke into his thoughts.

Barry turned to see a kid peeking around the edge of the dugout. A kid whose face was more familiar than any other pitcher’s

in the Summer Baseball Junior League.

“Why?” Barry asked Alec Frost, the High Street Bunkers’ fastball pitcher.

“Why?” Alec laughed. “Because you haven’t struck out yet. And that’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to strike you out so

bad the fans will forget they ever called you the hit-away kid.”

“Deeper! Deeper!”

Barry looked up and saw T.V. Adams motioning Tootsie Malone to back up toward the fence. T.V. did that a lot. He seemed to

have a real knack for predicting where the opposing batters were going to hit the ball.

As usual, he was right on the button. Arnie Nobles, the Junk Shop’s leadoff batter, had blasted a home run his first time

up, and it

looked as if he was ready to do it again. He was a tall kid and had a lot of power in his swing.

Crack!

He connected a two-two pitch for a long drive toward deep left field, just as T.V. had figured he might. If Tootsie hadn’t

played deep, the ball would have gone over his head for at least a triple. But Tootsie only had to take two steps back, raise

his gloved hand, and catch it.

Neither team scored again. The game went to Belk’s Junk Shoppers, 6 to 5.

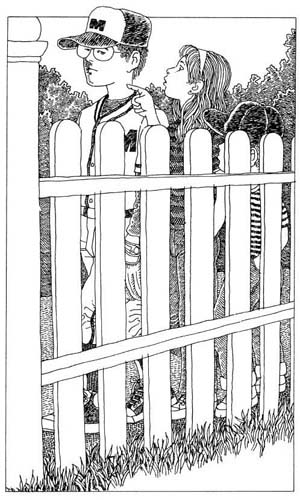

“Well, it made no difference anyway,” Susan said as she and Tommy walked home with Barry.

“What made no difference?” Barry asked.

“That you missed the ball,” she said. “We lost anyway.”

He glared at her. “Will you stop saying that?” he snapped. “You weren’t there; I was. And the ump called the guy out. That’s it.”

“I saw you drop it,” Susan said evenly. “And I know you like to cheat.”

“I do not!” he almost shouted. “Why do you say that?”

“Because it’s true,” Susan said. “Whenever we play board games, you —”

“Okay, okay!” Barry cut her off short. “Maybe I do cheat sometimes, but not all the time. And I don’t do it to hurt anybody.”

“Maybe not. But you hate to lose,” Susan argued. “And if you can cheat a little, and make up your own rules —”

“You sound like Coach Parker,” Barry interrupted her again. He tried not to let her arguments get under his skin, but he couldn’t

help it. “He said something to me about making up my own rules, too. What’s wrong with liking to win, anyway? Everybody likes

to win, don’t they?”

“Yes. But not by cheating.”

His face burned.

Cheating.

He was really beginning to hate that word. “Just don’t say anything about it to Mom and Dad,” he said gruffly. “I don’t want

them jumping on my back, too.”

Susan shrugged. “Okay by me. It’s your problem, not mine.”

Barry looked at her a long minute. He thought he’d feel better after she said that, but he didn’t. He felt worse.

At dinner, Barry’s father didn’t lose any time asking about the game. “How’d it come out?” he wanted to know.

“They lost!” Tommy yelled.

Everyone laughed. Tommy didn’t talk a lot, but whenever he did he made a point.

“You’re pretty quiet, Barry,” Mr. McGee observed. “Didn’t you get any hits?”

“Two singles and a walk,” he answered.

“Great!” His father beamed.

“And I made a tough catch,” Barry went on. He thought he could feel Susan’s eyes on him, but she was calmly eating. Suddenly

Barry didn’t have much of an appetite.

“Well, that’s good work, son,” Mr. McGee said proudly.

“There’s more. I dropped it …, ” Barry confessed. “But I pretended I didn’t.”

Barry’s parents stared at him. “You

what?”

his mother exclaimed.

Barry’s heart pounded. “I pretended I caught the ball,” he said.

Susan cleared her throat, and Barry looked at her. Their eyes locked, and he wished she could read his mind:

Keep out of this, little sister.

“And you got away with it?” his father said and shook his head. “Barry, I’m surprised at you.”

“And I’m disappointed,” his mother added,

her eyes wide as she looked at him. “What a terrible thing to do, Barry. I think you should tell Coach Parker.”

“It’s too late for that, Mom,” Barry said. “I’m sorry I did it. Okay? I promise I won’t do it again.”

Susan coughed, and their eyes clinched again.

“I said I won’t, and I won’t,” he said to her, his voice higher. “Okay?”

“Okay!” Susan cried. “I didn’t say a word, did I?”

“No, but you coughed,” he said. “That’s almost like saying something.”

“Okay, okay,” Mr. McGee cut in to settle the argument. “Barry apologized for what he did, and I’m sure he won’t let it happen

again. Now let’s finish our dinner.”

Barry breathed a sigh of relief. Boy! he thought. What a big deal over a stupid dropped ball!

The next morning Barry felt like skateboarding with José. Just as he lifted his green-and-white skateboard out of the closet,

he heard his sister’s high-pitched voice ask, “Can I skateboard with you? I won’t be in your way, I promise.”

He looked at her, and then at Tommy, who was clinging onto Susan’s blue jeans.

“Aw, Susan,” Barry moaned. “You’re always butting in.”

“Butting in? I didn’t butt in at the dinner table last night, did I?” she said with a gleam in her eye. “You cooked your own

goose.”

Barry had to smile. “Well, all right,” he said. “But Tommy stays here.” He leaned over and tickled his little brother’s chin.

“Keep an eye on Mom, pal. Okay?”

Tommy nodded. “Okay.”

Smiling triumphantly, Susan pulled out her red-and-white skateboard — which was just a few inches shorter than Barry’s and

had a

T-handlebar — and followed Barry out the door.

Once outside, they skateboarded up the cement walk. Their wheels clacked over the cracks, and more than once Susan’s board

rolled off the walk.

The second time Susan bent down to put her board back on the walk, Barry noticed something blue sticking out of her left-hand

pocket. That sister of mine, he thought. Her pockets are always bulging with some kind of junk.

“Hey, Barry!” he heard a familiar voice say, and he saw his friend José sweeping around the corner on his fancy skateboard.