The Hundred Years War (15 page)

Read The Hundred Years War Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

Also in 1377 the Duke of Anjou and the Constable again invaded Guyenne. The Seneschal, Sir Thomas Felton, was defeated and taken prisoner at Eymet in September, and Bergerac fell. But the Guyennois held firm, staying loyal to the Plantagenets. It is illuminating to remember Froissart’s considered opinion of the ‘Gascons’ :

‘ils

ne

sont point

estables’ —not a stable people, but preferring the English to the French and inclined to think that the English would always win. Indeed the Captal de Buch KG, that doughty squire from the sandy Landes, preferred to die in captivity rather than transfer his allegiance, although he was offered large sums of money. In 1379 a really capable Lieutenant arrived at Bordeaux, Lord Neville of Raby KG, from County Durham, who took the offensive, raiding in the style of the French Constable and sailing up the Gironde to recapture Mortagne. He is said to have retaken over eighty towns, fortresses and castles during his lieutenancy which lasted hardly more than a year.

‘ils

ne

sont point

estables’ —not a stable people, but preferring the English to the French and inclined to think that the English would always win. Indeed the Captal de Buch KG, that doughty squire from the sandy Landes, preferred to die in captivity rather than transfer his allegiance, although he was offered large sums of money. In 1379 a really capable Lieutenant arrived at Bordeaux, Lord Neville of Raby KG, from County Durham, who took the offensive, raiding in the style of the French Constable and sailing up the Gironde to recapture Mortagne. He is said to have retaken over eighty towns, fortresses and castles during his lieutenancy which lasted hardly more than a year.

The French were being contained on other fronts too. Although they had conquered Brittany they failed to take the port of Brest, which was relieved by a fleet under the Earl of Buckingham (Edward III’s youngest son, the future Duke of Gloucester). Then King Charles made the mistake of trying to confiscate Brittany from Duke John in the way that he had confiscated Aquitaine. The Bretons rallied

en masse

to their Duke-they had no desire to be united to the kingdom of France. Accompanied by Sir Robert Knollys, John returned to be received with joy, and he speedily recovered the west, eventually regaining the whole of his duchy. He ceded Brest to his English allies.

en masse

to their Duke-they had no desire to be united to the kingdom of France. Accompanied by Sir Robert Knollys, John returned to be received with joy, and he speedily recovered the west, eventually regaining the whole of his duchy. He ceded Brest to his English allies.

From Calais in 1377 the Deputy Sir Hugh Calveley raided Boulogne, burning ships and plundering. When the fortress of Marke in the Calais march fell to the French he retook it the same day. In 1378 the King of Navarre returned to the scene: he seems to have offered John of Gaunt the County of Evreux in return for the hand of his daughter Catherine. He also had an interesting scheme for poisoning Charles V (he was credited with having recently rid himself of an irritating cardinal by this method), a plot which was discovered when two of his agents were arrested. The Constable at once invaded Navarre’s last possessions in Normandy. But before fleeing to his Pyrenean kingdom, Charles the Bad managed to sell Cherbourg to the English, who rushed in a garrison.

In Normandy, Brittany and the Pas-de-Calais the ordinary people had continued to suffer from English garrisons. In 1371 1 that of Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte in the Contentin held 263 parishes in thrall, extracting over £13 from each. The English were greedier in Brittany; at Brest in 1384 they were to mulct every one of 160 parishes of nearly £40, and they had been equally rapacious at Vannes, Ploermel and Becherel. During the peace which followed Brétigny, and in the midst of all the reverses of the French reconquest, English troops, as well as blackmailing miserable peasants, also contrived to make a fat profit from ransoms. Sometimes enormous sums were realized. In 1365 Sir Matthew Gurney obtained nearly £5,000 for Jean de Laval, and in 1375 Lord Basset of Drayton got £2,000 for a prisoner. There were other ways in which a soldier might make money in addition to ransoms and loot. In 1375 the English garrison at Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte were paid £9,000 to surrender their fortress and march off peacefully. (Cherbourg replaced Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte as the scourge of Normandy.)

So long as men gave good service to the English King’s armies, the most deplorable conduct was tolerated. Sir Robert Knollys, said by Jean le Bel to have been one of the first

routiers,

was the principal captain of the Grand Company in 1358 and made 100,000 gold crowns (nearly £17,000) during that one year alone, when he controlled forty castles in the Loire valley-where the peasants were credited with throwing themselves into the river out of terror at the mere mention of his name-sacked the suburbs of Orleans, and threatened the Pope himself at Avignon. Charred gables were called ‘Knollys’s mitres’. Yet Edward III was so pleased with the damage inflicted by Sir Robert on the French that he gave him an official pardon. Later he became one of the King’s principal generals, leading as has been seen the

chevauchée

of 1370 and acting as chief-of-staff in another in 1380. (In 1370 he was paid the princely sum of 8s per day, or £146 a year.) Sir Robert amassed ‘regal wealth’ and built a palatial house in London as well as buying rich estates. He died full of years and honour in 1407. Even Sir John Chandos’s respected friend, Sir Hugh Calveley, led 2,000

routiers

to ravage Armagnac in the late 1360s ; like Knollys, who was his half-brother, Calveley had to seek pardon for felony. Later he was Deputy Lieutenant of Calais and then Governor of Brest.

routiers,

was the principal captain of the Grand Company in 1358 and made 100,000 gold crowns (nearly £17,000) during that one year alone, when he controlled forty castles in the Loire valley-where the peasants were credited with throwing themselves into the river out of terror at the mere mention of his name-sacked the suburbs of Orleans, and threatened the Pope himself at Avignon. Charred gables were called ‘Knollys’s mitres’. Yet Edward III was so pleased with the damage inflicted by Sir Robert on the French that he gave him an official pardon. Later he became one of the King’s principal generals, leading as has been seen the

chevauchée

of 1370 and acting as chief-of-staff in another in 1380. (In 1370 he was paid the princely sum of 8s per day, or £146 a year.) Sir Robert amassed ‘regal wealth’ and built a palatial house in London as well as buying rich estates. He died full of years and honour in 1407. Even Sir John Chandos’s respected friend, Sir Hugh Calveley, led 2,000

routiers

to ravage Armagnac in the late 1360s ; like Knollys, who was his half-brother, Calveley had to seek pardon for felony. Later he was Deputy Lieutenant of Calais and then Governor of Brest.

In 1376 the Commons petitioned the King to give a pardon like that of Knollys’ to Sir Nicholas Hawkwood, who was the most famous of all the ‘rutters’. The son of an Essex tanner and said to have been a London tailor in his youth, Hawkwood was pressed into Edward’s army as an ordinary archer, but by 1360 he was leading the

Tard-Venus

to blackmail the Pope. Two years later he took the notorious White Company over the Alps, to begin a long and glorious career as a

condottiere

in Italy; he ended with a bastard Visconti for his bride and a pension of over 3,000 gold ducats from the Florentine Republic.

Tard-Venus

to blackmail the Pope. Two years later he took the notorious White Company over the Alps, to begin a long and glorious career as a

condottiere

in Italy; he ended with a bastard Visconti for his bride and a pension of over 3,000 gold ducats from the Florentine Republic.

Another instance of social mobility was that of a certain bondsman of Saul in Norfolk. Conscripted by the commissioners of array in the 1340s to serve in Brittany, by 1373 he was Sir Robert Salle, captain of the fortress of Marck near Calais ; he had been knighted by King Edward and his courage was admired even by the snobbish Froissart, though his end was far from prosperous. In 1381 he was murdered in his home county by envious peasants. (A chronicler calls Sir Robert ‘a hardy and vigorous knight ... but a great thief and brawler’.)

The War was long remembered as a time to rise in the world. The fifteenth-century herald, Nicholas Upton, wrote that ‘in those days we saw many poor men serving in the wars of France ennobled’. Other serfs besides Robert Salle may have become gentlemen of coat-armour. Moreover as some gentry families were killed off there was room for new men to rise up and take their places.

Many great houses were paid for by booty won in France. Cooling Castle in Kent was built out of such resources by Lord Cobham in 1374, as was Bodiam in Sussex by Sir Edward Dallingridge (Captain of Brest in 1388), and probably Bolton in Yorkshire, which cost Sir Richard Scrope, a noted captain in the War, £120,000 and took eighteen years to complete. Soldiers anxious for their salvation founded religious establishments out of their ill-gotten gains, like the church at Pontefract endowed by Sir Robert Knollys, and Sir Walter Manny’s Charterhouse in London.

The English armies had earned their country a bad name, particularly the rank and file. Froissart-who, it must be remembered, was not a Frenchman but what today we would call a Belgian-considered the English ‘men of a haughty disposition, hot tempered and quickly moved to anger, difficult to pacify and to bring to sweet reason. They take delight in battles and slaughter. They are extremely covetous of the possessions of others, and are incapable by nature of joining in friendship or alliance with a foreign nation. There are no more untrustworthy people under the sun than the middle classes in England.’ However ‘the gentlefolk are upright and loyal by nature, while the ordinary people are cruel, perfidious and disloyal . . . they will not allow them [the upper classes] to have anything—even an egg or a chicken—without paying for it.’

But in war the English nobility showed themselves no less avaricious than their inferiors. It was not only the adventurers who made fortunes, as has been seen. So did-in the words of their inspired historian, the late K. B. McFarlane- ‘that maligned body of far-from-average men, the landed aristocracy of medieval England’. The same writer claims that ‘there is no truth in the theory that the aristocracy

started the war and left the mercenaries to finish it off‘, listing a host of noblemen who played a crucial part and in consequence amassed huge sums of money. In the Good Parliament of 1375 William Lord Latimer KG (who had fought at Crécy) was accused of having made £83,000 out of his captaincy of Bécherel-he undoubtedly managed to buy twelve English manors to add to his estates. Richard Fitzalan KG, Earl of Arundel and Surrey—popularly known as ‘Copped Hat’—left £60,000 in coin and bullion alone when he died in 1376 ; he was both an imaginative investor and a money-lender on a large scale, though in the view of McFarlane (the leading authority on the medieval English nobility) the original source of Arundel’s wealth was almost certainly the War. The Beauchamp Earls of Warwick were another noble family which did well out of the fourteenth-century campaigns in France, as did the great house of Stafford. Royal rewards for service in the field enabled the Cobhams to enter the peerage. Everyone, adventurer or magnate,

routier

or pressed archer, had good reason to keep the War going.

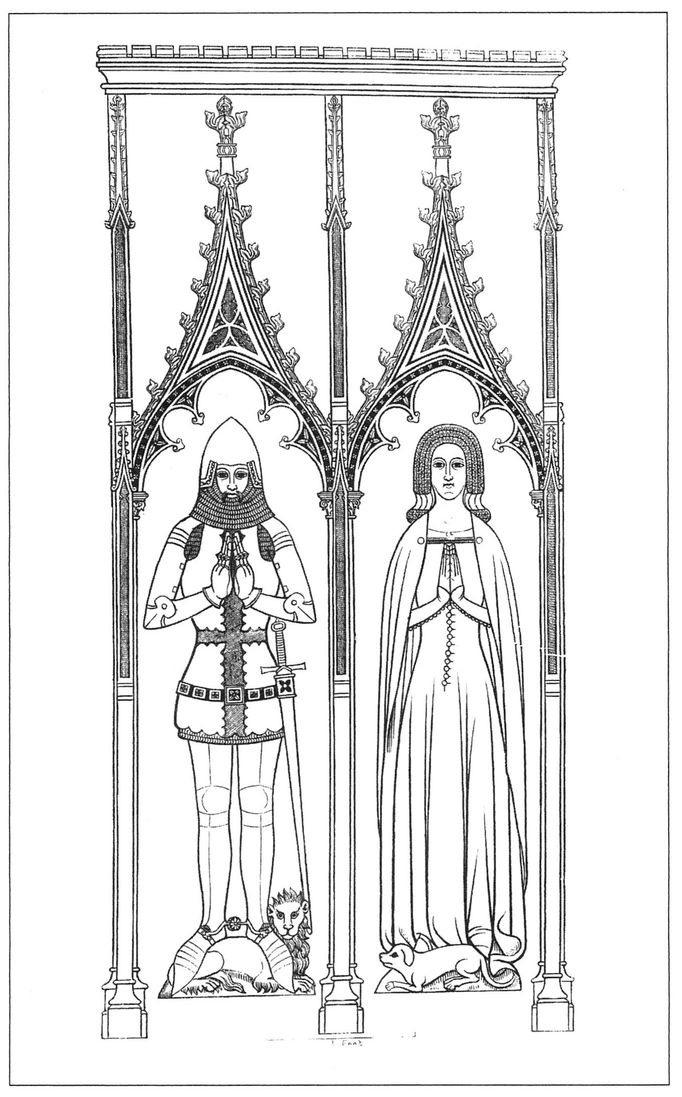

A knight of the Dallingridge family and his wife, c. 1390. This is probably Sir Edward Dallingridge, Captain of Brest in 1388, who built Bodiam. (From a brass at Fletching, Sussex)

routier

or pressed archer, had good reason to keep the War going.

Here one should emphasize that, although everyone had hopes, not every soldier actually made a fortune out of the Hundred Years War. At the Count of Foix’s castle at Orthez ‘a squire of Gascony called the Bascot of Mauléon, a man of fifty years of age, an expert man of arms’ was only too keen to tell Froissart his story while they sat by the fire waiting for midnight and for the Count to begin supper. The Bascot (Bastard) was a by-blow of a family of petty nobles and had had to support himself entirely by soldiering. ‘The first time I bore arms was under the Captal de Buch at the battle of Poitiers,’ said the Bascot. ‘I had that day three prisoners, a knight and two squires, of whom I had one with another 400,000 francs.’ He then went to Prussia to fight at the side of the Teutonic Knights, returning to put down the

jacquerie ;

and he was with King Edward during the Rheims campaign. After Brétigny he became Captain of a Free Company, riding with Hawkwood to Avignon to demand money from the Pope. He was in Brittany under Sir Hugh Calveley, taking prisoners at the battle of Auray ‘by whom I had 2,000 francs‘, and he accompanied the Black Prince to Spain. During the renewed war between France and England he kept the main chance in mind, capturing a castle near Albi which had since been worth ‘100,000 francs’ to him (presumably by extorting money from the surrounding countryside), though ‘I abide still good English and shall do while I live’. Yet although the Bascot travelled ‘as though he had been a great baron’ and ate off silver, he admitted he had known ‘as much loss as profit‘, that at times he had been so miserably poor—’so overthrown and pulled down’—that he could not afford even a horse. For all his campaigns and silver plate, he was ending as a mere household man of the Count of Foix. Many English men-at-arms must have been disappointed in the same way.

jacquerie ;

and he was with King Edward during the Rheims campaign. After Brétigny he became Captain of a Free Company, riding with Hawkwood to Avignon to demand money from the Pope. He was in Brittany under Sir Hugh Calveley, taking prisoners at the battle of Auray ‘by whom I had 2,000 francs‘, and he accompanied the Black Prince to Spain. During the renewed war between France and England he kept the main chance in mind, capturing a castle near Albi which had since been worth ‘100,000 francs’ to him (presumably by extorting money from the surrounding countryside), though ‘I abide still good English and shall do while I live’. Yet although the Bascot travelled ‘as though he had been a great baron’ and ate off silver, he admitted he had known ‘as much loss as profit‘, that at times he had been so miserably poor—’so overthrown and pulled down’—that he could not afford even a horse. For all his campaigns and silver plate, he was ending as a mere household man of the Count of Foix. Many English men-at-arms must have been disappointed in the same way.

In 1378 a new Pope was elected, the Italian Urban VI. The Papacy had returned to Rome in 1369 and Urban decided upon radical reforms which would diminish French influence. A group of cardinals were so alarmed that they declared Urban’s election invalid and chose another Pontiff, Clement VII. Charles was delighted and invited Clement to reinstall the Papacy at Avignon. Western Christendom was to be divided by the Great Schism for nearly half a century. Only the Scots and the Neapolitans joined the French in recognizing Clement, most countries trying to remain neutral. Naturally the English gave Urban enthusiastic support. Hitherto the Papacy had played a most valuable part in negotiating truces and attempting to make peace-now there was no international body to perform this work of mediation.

Charles V, iller than ever and approaching the end of his painful life, was so worn out and so depressed by his recent lack of success that he sued for peace. He offered the English all Aquitaine south of the Dordogne, together with Angouleme and a marriage between his daughter and Richard II ; the project collapsed when one of Urban’s cardinals arranged another match for the young English King. The French were increasingly restive under Charles’s ferocious taxation, which was essential for the war effort. There were revolts in Languedoc during which tax collectors were lynched. The risings were crushed but the King’s nerve was shaken and he abolished the most important levy, the hearth tax, thereby seriously diminishing the regular revenue which was vital for war.

Other books

Kill the Dead by Tanith Lee

The Unquiet Mind (The Greek Village Collection Book 8) by Sara Alexi

The Rogue Hunter by Lynsay Sands

The Guinea Pig Diaries by A. J. Jacobs

Reamde by Neal Stephenson

Vale of the Vole by Piers Anthony

Murder a la Richelieu (American Queens of Crime Book 2) by Anita Blackmon

Dance Away, Danger by Bourne, Alexa

The Sloan Men: Short Story by David Nickle

Will Shetterly - Witch Blood by Witch Blood (v1.0)