The Hundred Years War (16 page)

Read The Hundred Years War Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

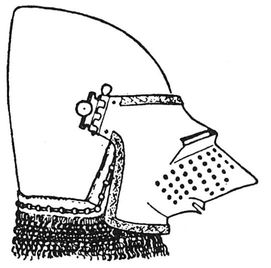

Seal of the Black Prince after the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360, when the English ruled a third of France. The inscription reads: ‘Seal of Edward, the King of England’s eldest son, Prince of Aquitaine and Wales, Duke of Cornwall and Earl of Chester.’

The English were nothing if not persevering. The Earl of Arundel, Marshal of the West, attacked Harfleur at Whitsun 1378, but met with such a warm reception that he had to beat a hasty retreat back to his ships. The same year he and Gaunt besieged Saint-Malo with no better success. In July 1380 the Earl’s brother, Sir John Arundel who was Marshal of England, led a nasty little raid on Brittany which demonstrated both the savagery of the English and their self righteous hatred of the Pope at Avignon. His troops stormed a convent and raped and tortured the nuns, carrying off some of the unfortunate women to amuse them for the rest of the raid. God, however, does not seem to have appreciated this fine theological distinction between schismatic and orthodox nuns, and a terrible storm sent Sir John to the bottom on the way home, with twenty ships and a thousand men. Only Sir Hugh Calveley and seven others were washed ashore alive.

In the same month the Earl of Buckingham and Sir Robert Knollys marched out of Calais on yet another

chevauchée.

They made for Brittany by a circular route which went through the Beauce and Vendôme before linking up with Duke John’s troops at Rennes. They did the usual fearful damage without being offered battle, and achieved nothing.

chevauchée.

They made for Brittany by a circular route which went through the Beauce and Vendôme before linking up with Duke John’s troops at Rennes. They did the usual fearful damage without being offered battle, and achieved nothing.

It was also in July 1380 that Bertrand du Guesclin fell ill and died while he was besieging a castle in the Auvergne. His master survived him less than three months, dying on 16 September at Vincennes from a heart attack. He was only forty-three. Yet even though he had failed to drive the English out of his country, Charles V had won back the greater part of that which had been conquered by Edward III.

5

Richard II: A Lost Peace 1380-1399

For ye [Richard] be always inclined to the pleasure of the Frenchmen and to take with them peace, to the confusion and dishonour of the realm of England.

Froissart

For the people of England ... said how Richard of Bordeaux would destroy them all if he be let alone. His heart is so French that he cannot hide it, but a day will come to pay for all.

Froissart

In 1380 the Kings of England and France were both minors. Richard II, born at Bordeaux in 1367, grew up to be fastidious and overbearing, with a streak of megalomania and a neurotic flair for making enemies. Charles VI, a year younger, took after his grandfather John II in combining an excessive love of pleasure with a pugnacious and unbalanced temperament. Both these monarchs were surrounded by greedy, opinionated uncles. In England the enormously rich and powerful John of Gaunt so obviously thought that he deserved a throne himself that some contemporaries suspected him of seeking to supplant young Richard ; the Earl of Cambridge was a timid nonentity—‘a prince that loved his ease and little business’—but the youngest uncle Thomas of Woodstock, Earl of Buckingham and future Duke of Gloucester, was as ambitious as he was violent-tempered and would later intrigue murderously against his nephew’s government. The three English royal Dukes reluctantly acquiesced in the realm being ruled by a council chosen by Parliament. In France, on the other hand, Philip the Bold of Burgundy soon governed the kingdom as he pleased, the Duke of Anjou becoming more interested in pursuing a claim to the Neapolitan throne, while the Duke of Berry was immersed in a lavish patronage of the arts.

The War in these years was an international struggle which was not restricted to England and France. At the beginning of Richard II’s reign the English Parliament spoke fearfully of all the wars in ‘France, Spain, Ireland, Aquitaine, Brittany and others’—which would soon extend to Flanders, Scotland and even Portugal. The conflict was further complicated by the schism between Rome and Avignon ; there was no longer an impartial Pope to mediate. Moreover by now it was the French rather than the English who were the aggressors in Guyenne and at sea, and England went in fear of invasion.

The most urgent tasks of Richard II’s Council were to find ships to fight the combined French and Castilian fleet which was raiding the south coast, and to maintain the garrisons on the French coast which kept open the sea-route to Guyenne. The latter were Calais, Cherbourg, Brest and Bayonne, the ‘barbicans of the realm’, and in 1377 their yearly maintenance cost no less than £46,000. The Commons complained that it was not their duty to find money for foreign wars, and by 1380 the Crown Jewels were in pawn, several large loans for defence could not be serviced and the royal treasury was completely exhausted ; none of the troops in the French garrisons had been paid for twenty weeks, while the Earl of Buckingham’s army in Brittany was six months in arrears. Reluctantly Parliament agreed to a graded poll tax on every soul in the kingdom save paupers ‘as well for the safety of the realm as for the keeping of the sea’.

Beverstone Castle, (Gloucestershire. ‘A castic builded by one of the Berkeleys of spoil that he won in France ... a pile at that time very pretty.’ (Leland)

Bodiam Castle, Sussex. Said to have been built from the proceeds of French plunder by Sir Edward Dallingridge, Captain of Brest.

A tax of a groat (4d) a head was a cruel burden on serfs who toiled on the land without wages. They were already unsettled by the depopulation of the Black Death ; it had made their labour saleable, yet they were unable to leave their masters’ manors for paid employment. In May 1381 the bondsmen of Kent, Sussex, Essex and Bedford rose in revolt, marching on London under the banner of St George and bringing their bows. (It is revealing that in Kent they would take no one living within twelve leagues of the sea, whose job it was to guard the coast.) En route the ‘true commons’ killed any tax collectors they could catch, sacked manor houses and monasteries and molested the Queen Mother. In London they killed some Flemings and a number of rich citizens, released prisoners from the gaols, burnt John of Gaunt’s Palace of the Savoy and the Priory of the Knights of St John, and stormed the Tower of London where they hacked off the heads of the Archbishop of Canterbury, who was the Lord Chancellor, and of the Prior of St John who was the Treasurer. Froissart says that ‘England was at a point to have been lost beyond recovery’ but adds disdainfully, ‘three fourths of these people could not tell what to ask or demand but followed each other like beasts’. They forced the young King to meet them at Smith-field, but when their leader Wat Tyler was cut down before their eyes by the Lord Mayor ‘these ungracious people’ scattered in panic and the rising was over. Hangings continued all through the summer. Undoubtedly war taxation was the spark which had set off the Peasants’ Revolt.

Taxation caused similar risings in France. Anjou was President of the Council until his departure for Naples in 1382 and during his brief regime re-introduced the taxes abolished by Charles V. The enraged Parisians broke into the arsenal, seized weapons and made themselves masters of the capital, hunting down the tax collectors ; there were risings of the same sort in other northern towns and a full-scale insurrection in the south. Only Philip of Burgundy’s firmness saved the situation. He quickly gathered troops and crushed the mobs. For the next six years he ruled France.

Economic troubles were crippling England’s ability to fight, let alone to conquer. The wool trade had been throttled by excessive taxation, while people were paying nearly double for their wine ; many vineyards in Guyenne had been abandoned because of French devastation, and shipments between Bordeaux and Southampton were much more expensive as vessels had to sail in armed convoys to protect themselves. In 1381, 1382 and 1383 Parliament again refused to grant taxes for war. In consequence the garrisons suffered-during this time the Captain of Cherbourg’s pay was reduced from £10,000 to £2,000-and the troops had to live almost entirely off ransoms and the

pâtis.

pâtis.

Meanwhile the Duke of Burgundy was closing his grip on Flanders. Since 1379 his father-in-law Count Louis de Male had been fighting the weavers of Ghent, and in 1382 they defeated him ; soon their

ruwaert

(or regent) Philip van Artevelde, the son of Edward III’s old friend, had overrun the entire country. Louis appealed to his son-in-law for help, Artevelde to the English. King Richard prepared to lead an army to Flanders but the Commons refused to grant the money. At Roosebeke in November 1382 the French overwhelmed the Flemish pikemen ‘and slew them without pity, as though they had been but dogs’ : Artevelde was among the slain. Count Louis himself died the year after, and henceforward Philip of Burgundy was Count of Flanders.

ruwaert

(or regent) Philip van Artevelde, the son of Edward III’s old friend, had overrun the entire country. Louis appealed to his son-in-law for help, Artevelde to the English. King Richard prepared to lead an army to Flanders but the Commons refused to grant the money. At Roosebeke in November 1382 the French overwhelmed the Flemish pikemen ‘and slew them without pity, as though they had been but dogs’ : Artevelde was among the slain. Count Louis himself died the year after, and henceforward Philip of Burgundy was Count of Flanders.

The impecunious English government found an ally in Pope Urban VI, who, alarmed at the success of the French ‘Clementists’, wrote to the English bishops ordering a tax on clerical wealth to subsidize a crusade against the Anti-Pope’s supporters. They preached with such eloquence that many Englishmen believed they could not enter paradise unless they contributed to so holy a cause ; in the diocese of London alone ‘there was gathered a tun full of gold and silver’. The ‘Crusade’ was led by a young Bishop, Henry Despenser of Norwich, who had a taste for war and flew a splendid personal banner. He landed at Calais in April 1383 with perhaps 2,000 men, including Sir Hugh Calveley. They advanced along the Flemish coast, taking several towns and besieging Ypres, although Flanders was impeccably Urbanist. When a large French army advanced to meet them, they retreated with inglorious haste, to be besieged in their turn at Gravelines from where they had to be rescued by the Bretons. The Bishop returned to England and was impeached for his pains.

Other books

The Forgiving Hour by Robin Lee Hatcher

Lord of My Heart by Jo Beverley

The Empress's New Lingerie and Other Erotic Fairy Tales by Hillary Rollins

Unraveled by Sefton, Maggie

The Worlds We Make by Megan Crewe

Throne by Phil Tucker

Captured by Time by Carolyn Faulkner, Alta Hensley

Raining Light (Fate's Intent Book 5) by Bowles, April

Prince Charming Can Wait (Ever After) by Rowe, Stephanie