The I Ching or Book of Changes (120 page)

As revolutions in nature take place according to fixed laws and thus give rise to the cycle of the year, so political revolutions—these can become necessary at times for doing away with a state of decay—must follow definite laws. First, one must be able to await the right moment. Second, one must proceed in the right way, so that one will have the sympathy of the people and so that excesses will be avoided. Third, one must be correct and entirely free of all selfish motives. Fourth, the change must answer a real need. This was the character of the great revolutions brought about in the past by the rulers T’ang and Wu.

THE IMAGE

Fire in the lake: the image of REVOLUTION.

Thus the superior man

Sets the calendar in order

And makes the seasons clear.

Fire in the lake causes a revolution. The water puts out the fire, and the fire makes the water evaporate. Arrangement of the calendar is suggested by Tui, which means a magician, a

calendar maker. Making clear is suggested by Li, whose attribute is clarity.

THE LINES

Nine at the beginning:

a

) Wrapped in the hide of a yellow cow.

b

) “Wrapped in the hide of a yellow cow.” One should not act thus.

One of the animals belonging to the trigram Li is the cow. The hide (

ko

) is suggested by the name of the hexagram, which means hide or molting. Yellow is the color of the second (middle) line, by which this first line is held fast. The present line is strong, and the trigram Li, to which it belongs, presses upward; thus it might be tempted to start a revolution. But the nine in the fourth place has no relationship with it, nor has the six in the second place, so that the moment for action has not yet come.

Six in the second place:

a

) When one’s own day comes, one may create revolution.

Starting brings good fortune.

No blame.

b

) “When one’s own day comes, one may create revolution.” Action brings splendid success.

This line is correct, central, and clear. The place is that of the official. As to connections above, it is in the relationship of correspondence to the ruler of the hexagram, the nine in the fifth place, and therefore has the potentiality of successful action. This is the moment indicated by the Judgment as being right for winning confidence (as regards the meaning of “one’s own day,”

chi jih

, cf. above). Here the configuration is especially clear: the trigram Li suggests day, while the middle line holds the place representing the earth, which stands in the southwest next to Li (south).

Nine in the third place:

a

) Starting brings misfortune.

Perseverance brings danger.

When talk of revolution has gone the rounds three times,

One may commit himself,

And men will believe him.

b

) “When talk of revolution has gone the rounds three times, one may commit himself.” If not, how far are things to be allowed to go?

This line is strong and clear and in the place of transition, but these very circumstances suggest danger of too great haste. Hence one should wait until the time is ripe. The relationship with the top line is not taken into account, because the latter is already bound to the fifth line. Therefore going prematurely would bring danger. If fire is to be effective against water, it must act with absolute determination. Success is possible only if all three lines form a single unit.

Nine in the fourth place:

a

) Remorse disappears. Men believe him.

Changing the form of government brings good fortune.

b

) The good fortune in changing the form of government is due to the fact that one’s conviction meets with belief.

As a strong line in a yielding place, this line is harmoniously balanced. It is like in kind to the ruler of the hexagram and in alliance with him, hence it meets with belief. Here the time for change has come. When the text speaks not only of revolution but also of change and alteration, it means that while revolution merely does away with the old, the idea of change points at the same time to introduction of the new.

Nine in the fifth place:

a

) The great man changes like a tiger.

Even before he questions the oracle

He is believed.

b

) “The great man changes like a tiger”: his marking is distinct.

This line is related to the six in the second place and therefore has the clarity of Li at its disposal. The trigram Tui, in which this is the central line, stands in the west, the place of the white tiger. The season of the year corresponding with this trigram is autumn, when animals change their coats.

Six at the top:

a

) The superior man changes like a panther.

The inferior man molts in the face.

Starting brings misfortune.

To remain persevering brings good fortune.

b

) “The superior man changes like a panther.” His marking is more delicate.

“The inferior man molts in the face.” He is devoted and obeys the prince.

The rulers of the hexagram are the six in the fifth place and the nine at the top. The idea on which the hexagram Ting is based is that of the nourishing of worthy men. The six in the fifth place honors the venerable man represented by the nine at the top. The image is derived from the way in which the rings and ears of the

ting

1

fit into each other.

The Sequence

Nothing transforms things so much as the

ting

. Hence there follows the hexagram of THE CALDRON.

The transformations wrought by Ting are on the one hand the changes produced in food by cooking, and on the other, in a figurative sense, the revolutionary effects resulting from the joint work of a prince and a sage.

Miscellaneous Notes

THE CALDRON means taking up the new.

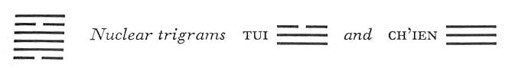

The hexagram is structurally the inverse of the preceding one; in meaning also it presents a transformation. While Ko treats of revolution as such in its negative aspect, Ting shows the correct way of going about social reorganization. The two primary trigrams move in such a way that their action is

mutually reinforcing. The nuclear trigrams Ch’ien and Tui, which mean metal, complete the idea of the

ting

as a sacred ceremonial vessel. These old bronze vessels—as still occasionally found in excavations—have been connected throughout all time with the loftiest expressions of Chinese civilization.

THE JUDGMENT

THE CALDRON. Supreme good fortune.

Success.

Commentary on the Decision

THE CALDRON is the image of an object. When one causes wood to penetrate fire, food is cooked. The holy man cooks in order to sacrifice to God the Lord, and he cooks feasts in order to nourish the holy and the worthy.

Through gentleness the ear and eye become sharp and clear. The yielding advances and goes upward. It attains the middle and finds correspondence in the firm; hence there is supreme success.

The whole hexagram, with its sequence of divided and undivided lines, is the image of a

ting

, from the legs below to the handle rings at the top. The trigram Sun below means wood and penetration; Li above means fire. Thus wood is put into fire, and the fire is kept up for the preparation of the meal. Strictly speaking, food is of course not cooked in the

ting

but is served in it after being cooked in the kitchen; nevertheless, the symbol of the

ting

carries also the idea of the preparation of food. The

ting

is a ceremonial vessel reserved for use in sacrifices and banquets, and herein lies the contrast between this hexagram and Ching, THE WELL (

48

), which connotes nourishment of the people. In a sacrifice to God only one animal is needed, because it is not the gift but the sentiment that counts. For the entertainment of guests abundant food and great lavishness are needed. The upper trigram Li is eye, the fifth line stands for the ears of the

ting

; thus the image of eye and ear is suggested. The lower trigram Sun is the Gentle, the adaptive.

Thereby the eye and ear become sharp and clear (clarity is the attribute of the trigram Li).

The yielding element that moves upward is the ruler of the hexagram in the fifth place; it stands in the relationship of correspondence to the strong assistant, the nine in the second place, hence has success. In ancient China nine

ting

were the symbol of sovereignty, hence the favorable oracle.

THE IMAGE

Fire over wood:

The image of THE CALDRON.

Thus the superior man consolidates his fate

By making his position correct.

Fire over wood is the image not of the

ting

itself but of its use. Fire burns continuously when wood is under it. Life also must be kept alight, in order to remain so conditioned that the sources of life are perpetually renewed. Obviously the same is true of the life of a community or of a state. Here too relationships and positions must be so regulated that the resulting order has duration. In this way the decree of fate whereby rulership falls to a particular house becomes established.

THE LINES

Six at the beginning:

a

) A

ting

with legs upturned.

Furthers removal of stagnating stuff.

One takes a concubine for the sake of her son.

No blame.

b

) “A

ting

with legs upturned.” This is still not wrong.

“Furthers removal of stagnating stuff,” in order to be able to follow the man of worth.

The line at the bottom means the legs of the

ting

.

2

Since the line is weak and stands at the beginning, the implication arises

that before cooking one must turn the

ting

upside down to throw out the old food remnants. The line has a connection by position with the central and strong line next to it; hence the idea of a concubine (weak and subordinated).