The I Ching or Book of Changes (122 page)

Then follow laughing words—ha, ha!

Good fortune.

b

) “Shock comes—oh, oh!” Fear brings good fortune.

“Laughing words—ha, ha!” Afterward one has a rule.

A part of the Judgment, and of the commentary on it, is given here word for word, as is occasionally done in the case of the ruler of a hexagram. The strong line at the beginning initiating the movement from below shows the quintessence of the whole situation.

Six in the second place:

a

) Shock comes bringing danger.

A hundred thousand times

You lose your treasures

And must climb the nine hills.

Do not go in pursuit of them.

After seven days you will get them back again.

b

) “Shock comes bringing danger.” It rests upon a firm line.

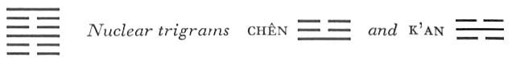

Since the first line presses upward with powerful shock, there can be no thought of a relationship of holding together between it and this weak line in a weak place. But the line is central and correct, and is therefore affected only externally by the threatening danger, just as a thunderstorm causes only momentary shock. Danger is indicated by the nuclear trigram K’an, under which the line stands. Flight to the hills is suggested by the lower nuclear trigram Kên, mountain. Seven is the number

indicating return, which restores the old conditions after the situations of all of the six lines have changed.

Six in the third place:

a

) Shock comes and makes one distraught.

If shock spurs to action

One remains free of misfortune.

b

) “Shock comes and makes one distraught.” The place is not the appropriate one.

The word

su

, here rendered by “distraught,” denotes literally the reviving movements of insects still numb and stiff after their winter sleep. The place is not the proper one, for the place is strong and the line weak; therefore it is not equal to the shock of the position. Hence it must allow itself to be set in motion by the shock. Through movement a weak line becomes a strong line. Thus one becomes equal to shock.

Nine in the fourth place:

a

) Shock is mired.

b

) “Shock is mired.” It is not yet brilliant enough.

The line itself is strong, but its strength is impaired by the weakness of the place. Furthermore, it is in the nuclear trigram K’an, just where the pit lies, and also at the top of the nuclear trigram Kên, Keeping Still. Thus the strong nature of the line cannot become effectual; it does not show enough brilliance, hence is caught fast in the mire.

Six in the fifth place:

a

) Shock goes hither and thither.

Danger.

However, nothing at all is lost.

Yet there are things to be done.

b

) “Shock goes hither and thither. Danger.” One walks in danger.

The “things to be done” are in the middle, hence nothing at all is lost.

The line is central, like the six in the second place. But while in the latter case danger threatens (nuclear trigram K’an), here it has been overcome and one is already on the hill (nuclear trigram Kên). Hence one loses nothing. The point is to hold firmly to the central position and thus to conserve for oneself the strength inherent in it—the fifth place being the place of the ruler. The six in the second place is the official. An official may lose his property temporarily, but all of it can be replaced. The six in the fifth place, however, is the ruler; and his possessions consist of land and people. These must not be lost. Such loss can be prevented if one maintains a central position and behaves correctly.

Six at the top:

a

) Shock brings ruin and terrified gazing around.

Going ahead brings misfortune.

If it has not yet touched one’s own body

But has reached one’s neighbor first,

There is no blame.

One’s comrades have something to talk about.

b

) “Shock brings ruin.” He has not attained the middle.

Misfortune, but no blame. One is warned by the fear for one’s neighbor.

This line is related to the third, which is the comrade who has something to say. The fifth line is the neighbor. Here a weak line stands at the climax of shock and is therefore inherently not equal to it. The shock threatens ruin as in an earthquake, hence the terrified gazing around. Trying to undertake something under such conditions would lead to misfortune. But if one takes warning from the experience of one’s neighbor—in this case the fifth line—and remains calm, mistakes are avoided. The third line, the comrade, is forced by the situation to move, hence cannot understand why the sixth line stays calm. However, the difference in behavior is the result of the difference in place. Therefore one must be wholly independent in one’s actions.

52. Kên / Keeping Still, Mountain

Here also, strictly speaking, the two light lines are the rulers of the hexagram. But since the meaning of the hexagram of KEEPING STILL is based on the fact that the light element stands still, the third line does not count as a ruler, and only the line at the top is so regarded.

The Sequence

Things cannot move continuously, one must make them stop. Hence there follows the hexagram of KEEPING STILL. Keeping Still means stopping.

Miscellaneous Notes

KEEPING STILL means stopping.

This hexagram is the inverse of the preceding one. It is formed by doubling of the trigram Kên, the youngest son, the mountain. The place of Kên is in the northeast, between K’an in the north and Chên in the east. It is the mysterious place where all things begin and end, where death and birth pass one into the other. The attribute of the hexagram is keeping still, because the strong lines, whose trend is upward, have attained their goal.

THE JUDGMENT

KEEPING STILL. Keeping his back still

So that he no longer feels his body.

He goes into his courtyard

And does not see his people.

No blame.

Commentary on the Decision

KEEPING STILL means stopping.

When it is time to stop, then stop.

When it is time to advance, then advance.

Thus movement and rest do not miss the right time,

And their course becomes bright and clear.

Keeping his stopping still

1

means stopping in his place. Those above and those below are in opposition and have nothing in common. Therefore it is said: “He does not feel his body. He goes into his courtyard and does not see his people. No blame.”

The nature of the hexagram predicates a separation of the upper and the lower trigram. This is indicated also by the divergent movements of the nuclear trigrams, the upper going upward and the lower downward. Keeping still is the meaning of the hexagram itself, movement is the meaning of the nuclear trigrams. Therefore it is explained that movement and stopping, each at the right time, are both features of rest: the one is continuance in a state of movement, the other continuance in a state of rest. The hexagram Kên has an inner brilliance, because the light line at the top is above the two dark ones and so is not darkened; hence the saying: “Their course becomes bright and clear.”

The back is that part of the body which is invisible to oneself; keeping the back still symbolizes making the self still. The lower primary trigram indicates this keeping still of the back, so that one is no longer aware of one’s body, that is, of one’s personality. The upper primary trigram means courtyard. The

individual lines of the upper trigram have no relation to the corresponding lines of the lower trigram, hence the upper and the lower trigram turn their backs on each other, as it were. Hence one does not see the other persons in the courtyard.

THE IMAGE

Mountains standing close together:

The image of KEEPING STILL.

Thus the superior man

Does not permit his thoughts

To go beyond his situation.

The corresponding lines of the upper and the lower trigram do not stand in the relationship of correspondence in any of the hexagrams formed by doubling of a trigram. But only in the hexagram of KEEPING STILL is it expressly noted that the mountains have merely an outward connection; in the case of the other hexagrams so formed, a reciprocal movement [of the trigrams] is always presupposed. In KEEPING STILL the opposite of movement and interchange is represented. Accordingly, the lesson taught by the Image is that of restriction to what is within the limits of one’s position.

THE LINES

Six at the beginning:

a

) Keeping his toes still.

No blame.

Continued perseverance furthers.

b

) “Keeping his toes still”: what is right is not yet lost.

With respect to their images, the individual lines in this hexagram are reminiscent of the lines of Hsien, INFLUENCE (

31

). Thus the lowest line is again the symbol of the toes. The line is weak, therefore keeping still accords with the time and is not a mistake. It is important only that a weak nature of this sort should not become impatient but should possess enough perseverance to keep still.

Six in the second place:

a

) Keeping his calves still.

He cannot rescue him whom he follows.

His heart is not glad.

b

) “He cannot rescue him whom he follows.” Because this one does not turn toward him to listen to him.

The line that is followed by the six in the second place is the nine in the third place. The six in the second place is correct and central and would like to save not only itself but also the one it follows. But the nine in the third place is a strong line in the place of transition, and it is the lowest line of the nuclear trigram Chên, the Arousing; hence it is extremely restless. At the same time it is in the nuclear trigram K’an, the Abysmal, which means earache, hence the failure to hear. K’an is also the symbol of the heart; hence, “His heart is not glad.”

Nine in the third place:

a

) Keeping his hips still.

Making his sacrum stiff.

Dangerous. The heart suffocates.

b

) “Keeping his hips still.” There is danger that the heart may suffocate.

This line is in the middle of the nuclear trigram K’an, hence the allusion to the heart. At the same time it is the one light line between dark lines, and this indicates danger and confinement. Keeping still in this situation is dangerous. When the back is kept still one gains control over the whole body. The hips, however, form the boundary between the movements of the light and the dark forces. If rigidity occurs here, the heart will move aimlessly, the nerve paths will thereby be interrupted, and a suffocation of the heart is to be feared.