The Illustrious Dead (15 page)

Read The Illustrious Dead Online

Authors: Stephan Talty

Tags: #Biological History, #European History, #Science History, #Military History, #France, #Science

General Barclay and Kutuzov’s other generals stepped in to fill the leadership gap as best they could. The pattern of the flèches repeated itself at the redoubt. The chief of staff for the First Army had been rushing past the rear of the central fortification to take the injured Bagration’s men in hand, but he was shocked by how thoroughly the Russian line had been broken at the center. Ignoring Kutuzov’s orders, he rallied a battalion of infantrymen, took the jaegers under his command, and, along with elements from the 12th and 26th divisions, turned to counterattack, marching in line to the beat of a drummer. The French had suffered heavy casualties on the attack, particularly from grape-and canister shot, and couldn’t hold off the Russian attack. Some of them turned and ran, and the only sustained fire the advancing troops experienced was from the regimental gunners. The Russians took the redoubt back in ten minutes. The French had lost 3,850 men in the failed attempt to secure it.

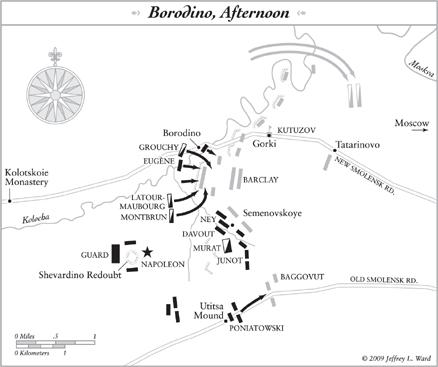

When the primitive fort was retaken around midday, there was a lull in the French forays against the Russian line. Even with his galvanizing battlefield leadership, Marshal Murat couldn’t push forward in the center without fresh troops, and his position was being raked with fire from the elevations of Semeonovskoie, which was constantly receiving fresh supplies of troops from Kutuzov’s right. Napoleon again agonized over whether to send in the Imperial Guard. He finally gave permission for the Young Guard’s artillery to move forward and begin shelling the village, and even agreed to send the elite troops themselves to join the battle, giving the French a chance to regroup and push toward the Russian reserves. But just as the units began to march toward the action, the emperor suddenly changed his mind, claiming that the existing troops were sufficient to hold the French line at Semeonovskoie. The Young Guard returned to its place behind the emperor.

In the south, starved of reinforcements, the French slowly began to give way to the bulging Russian line pushing down from the village. Murat sent another emissary to Napoleon, begging for troops. The officer pointed out the clouds of dust on the ridge at Semeonovskoie, under which the Russian cavalry was advancing. But just as the Young Guard prepared to move out, Napoleon reversed himself once more and halted their advance. Perhaps Napoleon was afraid that the Poles on the extreme right would let the Russians past, where they could circle behind Ney and Murat and annihilate those corps. Or perhaps Napoleon thought he could be outflanked on the left. Whatever the reasoning, he threw no more troops into the crucial engagement.

K

UTUZOV DID ATTEMPT

one daring foray against the French lines. Alerted that morning by the commander of the Cossacks that his horsemen had managed to ford the Kolocha River north of the French position, the Russian commander had sent a contingent of 8,000 hussars, Cossacks, and dragoons on a flanking maneuver against Napoleon’s left. General Barclay, delighted with the idea of outmaneuvering the French genius, had called the attack a “decisive blow.” But the Cossacks, known for their brilliance in harrying small groups of enemy soldiers, were going up against deployed lines of experienced soldiers, against which they were notoriously useless.

The mounted soldiers managed to panic the Bavarians holding the flank and cause a pell-mell retreat, news of which quickly made its way to Napoleon. But the attack ended up as more of a feint than a serious attempt to roll back the left flank. Without infantry to support the cavalry charges, the Russians satisfied themselves with scaring off the Bavarian horses and making a few passes at the 13th Infantry Division near Borodino, which formed up in squares and refused to wilt. With riders being dropped right and left by grapeshot and musket fire, the Cossacks and cavalrymen turned and raced back to their lines. The raid reinforced the idea that the Russians were past masters at defense but lacked the confidence or skills (especially the Cossacks) to press home an audacious offensive strike. What Napoleon lacked in men, the Russians lacked in tradition and mind-set.

The probing startled Napoleon, and clearly contributed to his decision to hold his reserves back. Marooned at the Shevardino Redoubt, he wasn’t convinced he knew what the Russians were up to. “My battle hasn’t begun yet,” he told his aides.

Most of the Grande Armée was held in suspended animation as Napoleon debated the endgame, alternately pacing and peering through his telescope. During the lull, however, men continued to die. The most outrageous waste came in Murat’s cavalry, which had been moved up around noon to fill the gaping hole in the line that opened up when Prince Eugène turned north to deal with the Cossack feint. The change in position had put these elite horsemen in range of the Russian 12-pounders at the Raevsky Redoubt.

The results were gruesome. The men sat in their saddles for several hours, serving as gorgeously dressed targets for the enemy gunners. Lieutenant von Schreckenstein, back with his Saxon cavalry brigade, watched as his comrades dropped amid the exploding shells. “For strong, healthy, well-mounted men a cavalry battle is nothing compared with what Napoleon made his cavalry put up with at Borodino …,” he wrote. “There can have been scarcely a man in those ranks and files whose neighbor did not crash to earth with his horse, or die from horrible wounds while screaming for help.” Shattered bits of helmet and iron breastplates came hurtling through the rows of horsemen, along with bits of bone and flesh. One cuirassier remembered that they could actually see the Russian artillerymen sighting their guns at their units. The troops had to remain unmoving as the guns were primed, loaded with ball, and then fired.

Captain Jean Bréaut des Marlots stood under the barrage with his men. “On every side one saw nothing but the dying and the dead,” he wrote. Twice during the three hours des Marlots reviewed his men, giving them encouragement and trying to judge who was holding up under the strain and who was slowly losing his nerve. He was chatting with one young officer who said all he wanted was a glass of water when the man was cut in two by a cannonball. Des Marlots turned to another officer and had just finished saying how awful it was that their comrade had been killed when the man’s horse was hit by a cannonball, knocking him to the ground. Writing an account for his sister, the captain told her how such random deaths from above gave him a deep sense of fatalism that carried him through. “I said to myself: ‘It is a lottery whether you survive or not. One has to die sometime.’” He vowed to be killed with honor rather than run from the field.

T

RYING TO REGAIN

the initiative, Napoleon ordered the artillery of the Guard to be wheeled from their positions forward to the edge of the plateau above Semeonovskoie. He would commit guns, but not the reserve itself. The 12-pounders added their reports to the unceasing roar.

A few minutes after two o’clock, Napoleon gave the order for a fresh assault against the Raevsky Redoubt in the center, which had become the Russians’ stronghold on the battlefield. He directed a three-pronged assault: three divisions of infantry would attack the structure head-on. From the French left, the III Corps of cavalry would move against the northern end and rear of the fortifications; from the right would come II and IV Corps, attacking the southern end and veering into the rear as well. Napoleon’s orders to General Auguste de Caulaincourt, the younger brother of his former Russian ambassador, were “Do what you did at Arzobispo!,” the 1809 battle where Caulaincourt had executed perfectly a daring encircling maneuver that won the day for the French. Now the general galloped off to lead his cavalry in a very different assignment: a frontal assault into withering artillery fire. Before the general left, he told his brother, “The fighting has become so hot that I don’t suppose I shall see you again. We will win, or I’ll get myself killed.” The elder Caulaincourt, knowing that his brother’s old war wounds caused him so much pain that he often wished for death, was shaken by the words.

Across the battlefield, General Barclay watched the enemy forces assemble. “I saw they were going to launch a ferocious attack,” he remembered. He called for the 1st Cuirassier Division to be brought up from the second line, a unit he had “intended to hoard for a decisive blow.” But his messenger returned to report that the division had been ordered (by whom, no one knew) to the extreme left flank to support the troops battling Poniatowski. It was symptomatic of a command structure where generals grabbed regiments whenever they could find them and stuck them in to fill holes, without coordination by Kutuzov. All Barclay could find were two regiments of cuirassiers, which he felt would be slaughtered in the first few moments of battle. He held them back until more units could be found.

As the clock ticked toward three o’clock, the Russians were forced to stand under a ferocious bombardment from the batteries around Semeonovskoie. Finally, the French infantry marched out, but the cavalry swept past them and reached the redoubt first. A squad of Polish and Saxon cuirassiers had been trotting from sector to sector all morning, avoiding the Russian guns and waiting impatiently to be called to action. Now they charged up the steep slope toward the battered earthworks and slipped their horses through the slots cut for the cannon, or wheeled their horses around the palisades and entered from behind, followed by the 5th Cuirassiers. Leading the 5th, General Caulaincourt was killed as he charged the walls, a musket shot cutting through his jugular. The Saxons and Poles smashed through the Russian defenses first, leaping over the bayonets of the defenders and chopping at the gunners with their sabers.

The first horsemen over the wall were met by musket fire but plunged into the enemy ranks regardless, and were met by bayonets, which the infantrymen stabbed up into the riders, breaking the blades on their iron breastplates or cutting blindly into thighs and groins. A roar went up from the French soldiers watching the action from the rear as they saw the sun wink off the cuirassiers’ helmets inside the distant redoubt. “It would be difficult to convey our feelings as we watched this brilliant feat of arms,” wrote Colonel Charles Griois, a cavalry officer, “perhaps without equal in the military annals of nations.” The Russians cut down the vanguard of cavalry, but more and more mounted troops poured in every available entryway and rushed in from behind, slashing at the enemy with their swords. Hopelessly outnumbered, the Russians fought to the death.

The body of one Russian gunner was decorated by three medals. “In one hand he held a broken sword, and with the other he was convulsively grasping the carriage of the gun he’d so valiantly fought with,” remembered one of his adversaries. But most of the dead were horribly chopped up and contorted, piled at the entrances, in the wolf pits outside the palisade walls, and trampled by horses or mixed in with dying mounts cut by bayonets and unable to stand. The fort was an abattoir in which the piles of dead told the story of the day like alternating layers of sedimentary soil. One soldier described the action inside as a “frenzy of slaughter,” with men slashing at each other or bludgeoning the enemy with musket stocks.

Barclay watched the action, rushing troops to fill the gaps the French were gashing in his front line. As the French attack progressed, he was conferring with another general when he looked up to see an enormous cloud of dust rolling over the turf toward the redoubt from the north. The Russians formed squares, with Barclay inside one, and waited for the cuirassiers to come within range. When the French appeared, the Russians fired and then advanced. One Russian general remembered what happened next:

It was a march into hell. In front of us was a mass of indeterminate depth, even as its front was impressive enough. To the left, a battery …and everywhere, French cavalry, waiting to cut off our way back…. We went straight for the enemy mass, while the huge battery hurled its ball at us.

The redoubt was taken by three thirty in the afternoon. General Caulaincourt was carried out on a white cloak clotted with blood, soon to be one of the heroes of Borodino. When word reached his brother, the diplomat began to weep silently and Napoleon offered to let him retire from the field. Caulaincourt said nothing but touched his hat in acknowledgment of the gesture.

The small number of Russian prisoners, only 800, testified to the implacable nature of the defense. Prince Eugène gathered up the remnants of the different cavalry units and sent them at the Russian reserves that Barclay had formed into a line. But again, a lack of manpower doomed the effort and the Russians retreated in good order, managing to take a number of the Raevsky guns with them.

Napoleon was incredulous that so few prisoners had been taken, even sending orderlies to the redoubts to make sure none were being held there. “These Russians let themselves be killed like automatons,” he complained. The prisoners would suffer terribly in the hands of the French. “Taken to Smolensk,” the illustrator Faber du Faur recalled. “They were dragged toward the Prussian frontier, tormented by hunger and deprived of even the most basic necessities.” Few of the captives would ever see Russia again.