The Incredible Human Journey (18 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

But this didn’t mean that earlier and anatomically different forms like

heidelbergensis

and Neanderthals should necessarily be excluded from our species. They represented lineages that had died out, as so many other, modern human lineages have done. And this means that we could view them, their cognitive capabilities, tool-making ability, and general humanity, in a different way. They were groups of humans that are no longer with us, not other, slightly inadequate species trodden underfoot by the snootily superior

sapiens

. I think it might be the medic in Stephen, with years of applying science in a human context, to diagnose and treat his young patients, that allowed him to investigate something as abstract and mathematical as genetics at a population level, but then put a human face on it.

And so we left Kampong Air Bah and the Lenggong Valley. Stephen had made a trip to the country and people he loved, and was returning with a fridgeful of new DNA samples. And I’d learnt a huge amount in just a few days, about surviving in a rainforest, trying to keep a threatened culture alive and the ivy branches that lay across South-East Asia. My next step would take me to another bit of Malaysia, but, this time, on an island.

Headhunting an Ancient Skull: Niah Cave, Borneo

So on I flew, to the Malaysian state of Sarawak on Borneo, and headed once more into the rainforest. Niah Cave is part of a system of caverns in the Gunong Subis limestone massif, about 15km from the coast in Sarawak. The cave lies within a national park, and we stayed at the park lodges. To get to the cave, I took a ferry across the Niah River and then walked 3.5km on boardwalks through the jungle to the cave itself.

I was excited by the prospect of visiting Niah; it was one of the places that had been on my wish list when we first started planning the series. It seemed like some archetypal archaeological site: a magnificent, vast natural cave in a mythical landscape of towering limestone escarpments, in the rainforest. And it was one of the most famous archaeological sites in South-East Asia.

Tom Harrison, then Director of Sarawak Museum, had excavated Niah between 1954 and 1967, with his wife Barbara. His first experience of Borneo had been on an ornithological expedition to the island, as an undergraduate, in 1932. He had gone there to study birds, but ended up becoming fascinated with the culture of the Dayak headhunters of Borneo, and this was the beginning of his career as an anthropologist. During the Second World War, Harrison had parachuted into the Borneo rainforest as part of a mission to recruit the native inhabitants of Borneo against the Japanese. Rather gruesomely, he successfully resurrected the practice of headhunting. Harrison stayed in Borneo until the Japanese surrendered – and beyond. After the war, he took up the post of Director of the Sarawak Museum. Tom Harrison knew of the very ancient human remains found on Java, the

Homo erectus

specimen that became known as ‘Java Man’, and he started digging at Niah Cave in search of ‘Borneo Man’.

1

I approached the cave through the massive, open rockshelter known as the Traders’ Cave, where twentieth-century gatherers of swiftlet nests would sell their strange harvest to soup makers. There are still nest collectors working the cave today. From the Traders’ Cave, I ascended wooden steps which then became an arched boardwalk, and suddenly, I was in front of the enormous West Mouth of the Great Cave of Niah. It was huge: 60m high and 180m across. I had seen photographs of it but, even so, I wasn’t prepared for the sheer scale of it. I could make out wooden poles hanging from the ceiling of the cave, and I watched a nest collector climb first a knotted rope, then up a pole, to the high ceiling of the cave. He threw down swiftlet nests to his colleagues below, small, plastic-looking cups, with feathers embedded in the dried saliva. Not an appetising prospect. In recent years, nest collecting had reached such a frenetic level that the swiftlet population had dived; now the collectors are working within strict quotas, but it still seemed cruel and unnecessary, like so many luxury foods. The nest collectors, though, made good money from this bizarre Chinese delicacy.

Tom Harrison found plenty of evidence of early human use of Niah Cave, including many burials from the Neolithic, dating to between 2500 and 5000 years ago.

2

I walked around the site of Harrison’s excavations in the West Mouth of the cave. The original trenches have been left open, and many Neolithic burials still lie exposed. This was quite strange: archaeologists normally remove human skeletal remains because, although bones may have survived for thousands of years, uncovering them changes their environment and they are likely to degrade. Certainly, these Neolithic burials looked a little the worse for wear. Tall trees had been cleared from the cave mouth of Niah, allowing light in for tourists to appreciate the sweeping grandeur of the enormous cavern. But light had also enabled green algae to grow across the limestone walls and ceiling of the cave, and all over the Neolithic burials.

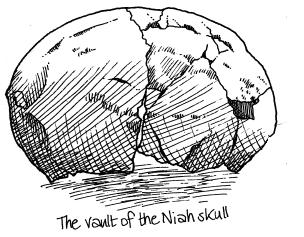

But I hadn’t come to see Neolithic burials: they were far too recent. Below the Neolithic cemetery, just within the West Mouth and cutting down through pond sediments, was Harrison’s 25ft-long Hell Trench. This part of the excavation gained its name from the conditions in which the archaeologists were working: hot, humid and hellish. But the swelteringly hard work in this trench paid off, when, in 1958, Tom Harrison discovered the ‘Deep Skull’. It was unmistakably a modern human, with a round braincase, and modern-looking browridges and occiput. From its depth, he must have anticipated that it would have been old. There was charcoal in the layer of sediment immediately above the skull, which Harrison sent off to be radiocarbon dated. When he got the results back, it transpired that he had found what was, at the time, the earliest evidence of modern humans outside Africa: the skull appeared to be 40,000 years old.

2

At the time, this date was met with disbelief: it seemed far too early a date for a modern human in Borneo.

The skull itself was normally kept in the Sarawak Museum in Kuching, but the curator, Ipoi Datan, had very kindly arranged to bring the skull back to its original findspot, and so I was to see the skull in the cave in which it was found. I carefully opened its cardboard box. The skull had been in many fragments when it was discovered, but had been glued together to make larger pieces. I carefully lifted these pieces out of the cotton wool that had cushioned them on the motorbike ride into the forest. There was a large domed piece that made up most of the calvarium, or top of the skull, a fragment of the left temporal bone, around the left ear, and another fragment of the base of the skull. The maxilla, with the upper teeth, had been left behind in Kuching, but I knew from the reports that the third molars or wisdom teeth had not erupted. This meant that this was the skull of a young person, in his or her late teens or early twenties. The base of the skull also showed signs that two of the bones had been in the process of fusing – at a joint with the grand name of the ‘spheno-occipital synchondrosis’ – another indication that this was the skull of a young adult.

It can be quite difficult to decide if a young skull like this is male or female. Many of the features that indicate maleness relate to the robusticity or chunkiness of a skull (as men are generally more muscly and heavily built than women), but these features are often still developing into a young man’s twenties. Many eighteen-year-old men still look quite girlish, although they may baulk at this. I really notice the difference, teaching at a university, between male students in the first and third year. They grow up in all sorts of ways, but their faces really do change over those three years. The Deep Skull looked female to me, but I had to bear in mind that this was the cranium of a young adult, and so I couldn’t be sure. Other researchers had reported the skull as ‘probable female’.

The square shape of the eye sockets, wide nose, slightly protruding jaw and the shape of the teeth fitted very well with what the researchers expected ancient South-East Asians – the ancestors of present-day Andaman Islanders, and Aboriginal populations throughout Malaysia, the Philippines and Australia – to have looked like.

2

Harrison had never published a full report on the site, and, in 2000, an international team of archaeologists, led by Graham Barker from Cambridge University and Ipoi Datan, who had brought the skull from the Sarawak Museum for me to examine, descended on Niah Cave.

3

Their mission was to recover information from the trenches, notebooks, photographs and excavated material from the original dig, and to carry out some new excavation as well. Harrison’s 40,000-year-old date for the Deep Skull had always been controversial. Some archaeologists had suggested that his dating was flawed, others that the skull could have been much more recent, perhaps even Neolithic, and that it had somehow been pushed down into deeper sediments, making it seem much older than it really was.

So one of the key challenges for Barker and his team was to find out if the skull really was as old as Harrison had claimed. Going back to Hell Trench, they were able to confirm the exact place where the Deep Skull had been discovered. It was clear to them that the skull could not have been pushed down into the sediments in which it was found. They then applied new dating techniques on the sediments in which the skull had been found, using state-of-the-art AMS radiocarbon dating on charcoal from the sediment, and uranium series dating on the bone itself. The new dates for the Deep Skull came out at around 39,000 to 45,000 years old, so Harrison’s claim for the great antiquity of the skull was vindicated.

There are a couple of other sites in the region with very old fossils. The Tabon Cave on the island of Palawan in the Philippines, just north of Borneo, has yielded a skull dated to around 17,000 years, but also a tibia which could be as old as 58,000 years, although this date needs to be confirmed.

4

A premolar – possibly that of a modern human – from Punung on Java may be even older.

5

Late Palaeolithic archaeological sites in Korea have been dated to 42,000 years ago, and there are some modern human remains from cave sites that have been estimated, by dating of associated remains, to be around 40,000 years old.

6

But the Deep Skull remains, fifty years after its discovery, the earliest definite evidence of modern humans in South-East Asia, and among the oldest outside Africa.

2

The re-excavation of Niah Cave also turned up more human bone, including a fragment of tibia and pieces of another skull. These other skull fragments were stained with ochre on the inside surface, leaving archaeologists to wonder whether it had been painted as part of a burial ritual, or even perhaps used as a paintpot.

As well as skeletal remains of the early people of Niah themselves, there was plenty of evidence of how they had lived, and the dates for human occupation of the cave went back even earlier than the Deep Skull. One of the important implications of findings from Niah Cave is that these hunter-gatherers were managing to survive in an environment that may

look

green and lush on the surface but is actually very difficult to find food in. Many plants that look quite palatable are actually poisonous, and the animals get very good at hiding in dense foliage. I had already seen the skills and knowledge needed by modern hunter-gatherers to obtain wild food in the Malaysian rainforest, and in Niah Cave there was evidence of the same sort of ingenuity and resourcefulness going back some 46,000 years.

Barker’s team analysed a huge volume of animal bone left over from Harrison’s excavations, giving them insights into the diet and hunting skills of the early occupants of Niah Cave. The animal bones came from layers dated to between 33,000 and 46,000 years ago. Many of the bones were burnt, probably the dumped remains of turned-out hearths – a bit of Palaeolithic housekeeping – while others had cut marks on them from butchery, so the archaeologists could be sure that humans had been involved. It seemed that the hunter-gatherers at Niah were managing to catch an enormous range of prey, from many different habitats around the cave: the bones belonged to a many different species including bearded pigs, leaf monkeys and monitor lizards.