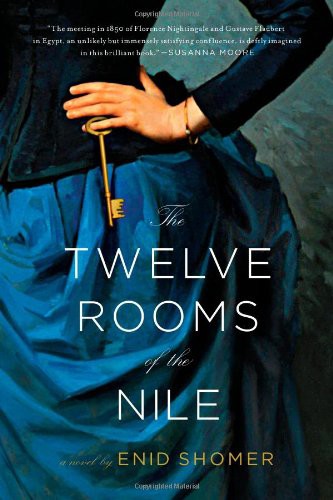

The Twelve Rooms of the Nile

Read The Twelve Rooms of the Nile Online

Authors: Enid Shomer

Tags: #Literary, #General, #Historical, #Fiction

Thank you for purchasing this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

Chapter 1: Father Mustache and the Father of Thinness

Chapter 4: La Vie De Florence Rossignol

Chapter 7: The World is Made of Water

Chapter 9: The Weighing of the Heart

Chapter 10: A Visit to the Patriarchs

Chapter 11: Frightful Row with Trout

Chapter 12: Lamentation at Philae

Chapter 16: A Cabinet of Relics

Chapter 23: “This is Traut’s Book”

Chapter 24: Lemon Ices and Raki

Chapter 30: The Ritual of Treading

Acknowledgments, Sources, and a Note

In memory of William Magazine

and for my family

—Nirah, Mike, Oren, and Paula

Is discontent a privilege? . . . Woman has nothing but her affections,—and this makes her at once more loving and less loved.

—FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE,

CASSANDRA

The future is the worst thing about the present. The question “What are you going to do?,” when it is cast in your face, is like an abyss in front of you that keeps moving ahead with each step you take.

—GUSTAVE FLAUBERT

To speak the names of the dead is to make them live again.

—THE BOOK OF THE DEAD

FATHER MUSTACHE AND THE FATHER OF THINNESS

H

ad the young Frenchman not been lost in thought, he might have caught his Baedeker as it jostled free of the gunwale and slipped into the river. Bound in red morocco with gilt lettering and gilt-edged pages, it was a costly gift from his dear mother.

At first the book floated, spread open like a bird with small red wings. But as the waters of the Nile darkened the onionskin pages already stained with Oriental sauces and cup after cup of Turkish coffee, they swelled like the gills of a drowning fish. His dragoman, Joseph, reached for it with an oar, but the attempt served only to push the guidebook farther under and soon it disappeared into the murky wake of the

cange

. The gentleman frowned.

The crew set about mooring the vessel on the riverbank. The Frenchman took a deep breath and realigned the incident in his mind, turning it the way you might a newspaper the better to scissor out an article. If he had to lose his guidebook, what better place than the Nile, that great liquid treasure pit? Let it molder in the deep,

among shepherds’ crooks and shards of clay oil lamps, or be heaved ashore with the river’s yearly inundation of silt. He pictured a workman or scientist retrieving it in the future, reading the inscription he’d written on the fly page in indelible ink: “G. Flaubert, author of the failed novel

The Temptation of Saint Anthony,

1849.” Maybe he would be remembered for something after all! But the thought only made him frown again. Ambition was a dull pain, like a continually broken heart.

The crew prepared to serve the midday meal. Egyptian cleverness extended not only upward to the immense, immovable majesty of the Pyramids, the Sphinx, and the gargantuan colonnades at Karnak, but also downward to the practical and portable, to folding stools, chairs, and tables, expandable fishnet sleeping hammocks, and sacs for foodstuffs. Where moments before the crew had trafficked the broad central planks of the deck, there now appeared a dining nook, shaded by muslin hoisted on poles and tied at the top like a fancy parasol. He watched Achmet float a white damask cloth onto the table, then lay pewter chargers and pink porcelain plates, and finally, neatly frame each table setting with utensils and drinking vessels. A ewer of red wine and two full wineglasses in the dead center of the table reminded him of a floral arrangement trailing two spilled roses.

On the foredeck, a Nubian crewman was chopping and cooking, while leaning on the mainmast of the skysails, Rais Ibrahim, the captain, haggled with a fishmonger. Soon enough a phalanx of tin trays laden with dolma—all manner of stuffed vegetables—would appear to rise unaided, levitating on the heads of the crew.

Gustave and his companion, Max, had left France four months earlier. They were sailing south to Abu Simbel, after which they would turn around and follow the current back toward Cairo, visiting more monuments at their leisure. Upon the completion of their river journey, now in its eighth week, they would tackle Greece, Syria, Palestine, and all of western Turkey from Smyrna to Constantinople. Later, perhaps Persia and India.

Most of their itinerary lay within the borders of the Ottomans,

who cared nothing, Gustave knew, for the connection to the classical past that so thrilled him. Genuflection at the altar of Graeco-Roman and Egyptian antiquity was to their thinking probably amusing if not idiotic. Their holy shrines lay farther east, in domains marked by a fastness of sand and abstinence. When, four decades earlier, they’d allowed the Elgin Marbles to be removed to England, it had ignited bidding wars among curators, archaeologists, and wealthy collectors for every torso, ossuary, and water jar. To the Turks this was not vandalism, but an opportunity to sell off useless debris. With their prohibition against the graven image, he imagined they might even be disgusted that a human form fetched up in stone could excite such ardor.

Though his hosts ruled a large chunk of the world, historians seemed to agree that a golden age based in raw courage and gallantry was behind them, that they now lived by collecting in tribute what they had once secured with the bloody scimitar. He admired the fact that unlike the Europeans, who were prone to wars of ideas, the Turks reigned benignly, ceding to their conquered peoples great latitude in the practice of religious and national customs. Or were they benign out of inefficiency? The sultans, caliphs, viceroys, emirs, sheiks, and pashas—they had countless names for grand and petty offices—ruled from an ornately disorganized web of bribery and corruption so bloated with excess that the empire had grown unwieldy as an elephant balanced on a ball. Someday it would tumble in an earth-shaking, ruined heap.

In the meantime, both he and Max entertained fantasies of returning home with a marble bust or two, possibly a mummy. For they had learned the secret to a successful tour of the Orient: baksheesh. A handful of drachmas or piastres opened the doors of private estates to the two young Frenchmen. Obscure ruins were lit by torchlight if necessary for their inspection, and skilled cicerones were assigned to guide them to hidden corners of antiquity. With the right attire, a modicum of financial resources, and a pouch bulging with documents adorned with diplomatic wax and ink flourishes, Europeans traveling

the Orient enjoyed the privileges of nobility. Lord knew that made for a stampede of them everywhere in the cities of the delta, if not yet on the river itself. Egypt was on the verge of becoming an industry. They would be among the last to see it before it was entirely corrupted by foreigners.

To burnish their air of importance, Max, the more savvy of the two, had secured official missions for them from two different ministries of the French government. Unpaid missions, to be sure, but nonetheless effective in connecting them to diplomats and commercial agents in the East. Gustave’s collection of gaseous bureaucratic prose commended him to the world beyond the Tuileries as a gentleman in the employ of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce with the task of collecting in ports and caravansaries information of interest to chambers of commerce in France. He had planned to dispense with his official designation upon arrival, but soon grasping its value, instructed his mother and friends to address their letters to

“Gustave Flaubert, chargé d’une mission en Orient.”

Max’s mission was substantive, and Gustave envied him it, though he was too lazy to have undertaken it himself. The Ministry of Public Instruction had charged Max with compiling a catalog of the ancient monuments. With the latest camera, Monsieur Du Camp could efficiently replace corps of savants and artists who in Napoleon’s day had performed this task. He was also charged with making life-sized facsimiles of the inscriptions, similar to stone rubbings, but producing an actual relief. These molds, or “squeezes,” made using wet paper, were simple but tedious to produce, and Max depended upon Gustave to assist in their manufacture. Much to his disgust, Gustave often wandered off or fell asleep precisely when he was needed.

The truth was that Gustave had never considered himself anything but a writer. He pictured his study at home, an airy consortium of books and flowered chintz, thriving potted plants, a bearskin rug and massive desk where he had devoted the last two years to his first novel. While other writers poured out their tales or allowed them to trickle forth like seasonal streams, he had carved

The Temptation of

Saint Anthony

from the very mountain of the French language. Then, after reading it aloud to them, his best friends Max and Bouilhet had pronounced it inferior, unworthy of publication. The recollection sent a sharp pain through his chest and arrested his breathing. The reverie of the writer’s life he would return to in his study at home vanished, like smoke on a wind.

He turned his attention to the crew approaching single-file amidships. On either side of them the waters of the Nile lapped like molten pewter touched with rivulets of gold. Hasan lowered a tray of delicacies, while above his shoulder, a gull’s wing fluttered like a feathery epaulet as the bird swooped onto the bow of the

cange

. I’m traveling in the world of Byron! he thought, surrounded not by shopkeepers and prim demoiselles, but men wearing fezzes, bare-chested under fancy red vests. Nota bene: trimmed with soutache and black silk embroidery, one of these vests would make the ideal gift for Louise. In the past few months, the memory of her infuriating possessiveness had faded somewhat, and he had begun to ponder her charms. Just now, as he sipped his wine, he recalled the disarming way on their first rendezvous she had turned to him and said, “Shall we kiss awhile, my darling?”

Each man had spent the morning in solitary chores, Gustave composing in his journal, Max readying the camera for the afternoon excursion.

Max appeared at the table and greeted him. “I will need your help,” he said. “Today we scout the temple of Derr.”

“Yes,” Gustave muttered. “I’m sure it will be grand.” He was remembering the Sphinx, that sublime surprise. He had seen drawings of Luxor, Giza, and Abu Simbel at an exhibition in Paris. The Sphinx, though, had existed only in his imagination until the instant he came upon it, a ferocious giant perched on the desert floor, its nose smeared flat as if bloodied in a brawl.

“There will be many inscriptions, many squeezes to be made.”