The Incredible Human Journey (26 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

‘I used to sit with my grandfather,’ he said. ‘Sit next to him, see him paint, tell stories. That’s how I learnt from him.’

‘Are there any children learning to paint at the moment?’ I asked.

‘Yeah, there are. Schoolkids. Some of them even made a clay-mation about the Turtle and Echidna story.’

(The tale of the Turtle and Echidna was a bizarre just-so story about how those animals originated. They had once both been women. One woman was meant to be looking after the other’s children but somehow ended up eating them instead. The children’s mother was understandably annoyed, and threw a stone at the greedy woman, which had stuck to her back and she became a long-necked turtle. The turtle, in turn, threw spears at the outraged mother, who became an echidna.)

All the artists I had met at the Arts Centre were men. ‘Are there any women artists?’ I asked Gabriel. ‘No, not really. The women make baskets – secret women’s work!’ he smiled. The baskets themselves were works of art. Woven from pandanus leaves, they were coloured with natural pigments which echoed the ochres used traditionally in the paintings, but with the reds, browns and oranges combined with green and yellow plant dyes. There was a great range of different basketwork in the Arts Centre, from large, flat trays and mats to string bags and small, fluted dilly bags. These little bucket-shaped bags were both practical and symbolic; they could be used to carry bush food or sacred objects. Just as Gabriel had learnt to paint from his grandfather, young girls would sit with their mothers and grandmothers, watching them weaving and listening to their Dreamtime stories. They would also learn the practicalities of how to collect pandanus, bush string, pigments and bush food.

3

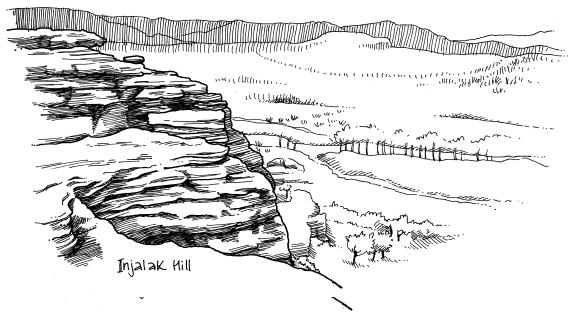

Gunbalanya is special not only for its thriving community of artists, but as an area containing a very rich concentration of rock art ‘galleries’, which can be visited only with permission from the traditional, Aboriginal landowners. I was lucky enough to be getting a personal guided tour by Wilfred and his cousin, Garry Djorlom. Gunbalanya lies on a coastal plain, just to the west of the ‘Stone Country’ of the Arnhem Land escarpment. The Arts Centre is named after Injalak Hill, an outlier of the escarpment, separated from the settlement by a lily-fringed billabong during the wet season.

I went up on Injalak Hill with Wilfred and Garry. Getting there was a feat in itself; we had Land Rovers which we could drive into the creek up to the tops of their bonnets, but there would be parts that were too deep. We had taken a flat-bottomed boat with us as well, to navigate the last section of the billabong, which would have been fine if the water had stayed deep, but sometimes we were trying to float in less than a foot of water. It would get too shallow to use the motor, then the bottom of the boat would scrape along on the gravel, like nails down a blackboard, and we’d be forced to get out and wade alongside the boat, pushing it. This was rather nerve-racking as I’d been told that there were crocodiles around. We kept a beady eye open and I was very pleased not to see any.

Eventually, we were back on dry land. Wilfred and Garry led me through tall grass (we were now on the lookout for snakes) and to the foot of Injalak Hill. We made our way up a narrow, winding path, between boulders which became larger as we climbed higher up the hillside. About halfway up, we paused on a flat outcrop and surveyed the landscape. We were looking down on the billabong, the lush green landscape, and Gunbalanya beyond. Garry told me about hunting in the bush. Although apparently living a settled existence, many of the Aboriginal families of Gunbalanya still went off into the countryside from time to time to find bush tucker. Garry said that people would do this when they’d had enough of eating bad, Western food from the supermarket.

Whole families would head off into the bush to live more naturally, as their ancestors had done. The land looked lush and bountiful: it had always been a good place for hunter-gatherers, with abundant food all year round, and rocky escarpments providing shelter from tropical monsoons.

We climbed further up the hill, and the ground levelled off. We were now in a clearing with a large, overhanging rock on one side. Garry and Wilfred gestured upwards: I looked at the rocky ceiling above me and an amazing sight met my eyes. The overhang was

covered

in paintings. It had been painted over and over: a great palimpsest of images stretching back who knows how many hundreds or thousands of years. The last paintings were done in the 1960s, and as far as Garry and Wilfred were concerned the earliest paintings went back into the Dreamtime, the time of their ancestors, when the world was young.

All across this rock face were paintings of animals. Garry pointed out the different species to me: echidna, crocodile, turtle, kangaroo, snake, and many, many types of freshwater fish, including whiskered catfish, fat barramundi and slender long tom. After all, this was Fish-Dreaming (Injalak) Hill. Beyond a kangaroo’s head, a human-like arm reached out. The colours – red and yellow ochres, white and black – and the patterns including the hatching, or

rarrk

– were familiar from the paintings I had seen down at the Arts Centre, as was the ‘X-ray’ style of the barramundi, showing its spine.

On first inspection, the paintings seemed to be about what animals were available in this rich environment: a sort of

à la carte

menu for hunter-gatherers. But although this was one level of meaning, the various animals also stood for other things, including features of the landscape. Aboriginal mythology was very firmly tied to geography. Creation stories described how land and waters had arisen, but also how particular elements of the countryside had come into being. Some ancestral beings had even changed into parts of the landscape, to become sacred sites.

Garry described how the children of Gunbalanya would still be brought up here to learn about their environment and their heritage from elders. The rock paintings were so much more than decoration: they were a method of communicating ideas. And, as I had already learnt, this tradition was much more ancient than writing.

‘Always pass it on, pass it on. That’s the real importance of painting,’ said Garry.

Higher up on the hill, I followed Garry and Wilfred down narrow corridors formed by cracks between enormous boulders. A niche in one rocky wall formed a canvas for a very special piece of rock art. No animals here – this image was purely mythological. ‘This is a picture of the creation mother: Yingana,’ Wilfred told me. He loved nothing better than telling a story. He had a wonderful voice: slow and measured, and, quite strangely, English-sounding. I later found out he had been brought up by missionaries (Gunbalanya was originally a mission town). He sounded like an English country vicar telling parables from the pulpit.

‘She came from the coast, travelling,’ he said. ‘She is carrying lots and lots of dilly bags.’ The woman was pictured wearing a headband, from which were hanging fourteen or so stripy dilly bags, and Wilfred said that each one contained a baby.

‘Once she came, she put down one baby, and gave him a language and a skin-name, a clan. Then she came to another place. The second one, she gave him a different clan, skin-name, language. Then she kept travelling. The third one, she gave him a different language, different moiety. She kept travelling, putting down these babies – the ancestors of us.’

The story went on. Yingana was seeding Australia with its original people.

‘I’ve been trying to find out how people first got to Australia,’ I said. ‘I’ve been looking at fossils and genes. We think that perhaps the ancestors came from the north, from across the sea.’

‘From the north – yes. Creation mother may have come ashore from Macassar way, from somewhere in Indonesia. That’s my guess.’

This was fascinating. But it was probably wasn’t the amazing coincidence it at first seemed. Wilfred was an educated man. He knew that Macassar (Indonesia) lay to the north, but he was also prepared to incorporate this knowledge into his understanding of the traditional stories of the origin of his people.

But other Aboriginal stories also seem to have their starting point in the north. Bruce Chatwin tried to trace ‘songlines’, the sacred songs that describe the journeys of ancestors across the landscape of Australia, and he wrote:

The main Songlines in Australia appear to enter the country from the north or the north-west – from across the Timor Sea or the Torres Sea – and from there weave their way southwards across the continent. One has the impression that they represent the routes of the first Australians – and that they have come from somewhere else.

We emerged from between the clefts in the massive boulders on to an eagle’s-nest viewpoint overlooking Gunbalanya and the hills around: Turtle Dreaming Hill and Magpie Goose Dreaming Hill. I sat near the edge, with Wilfred and Garry, looking out at the land their ancestors had inhabited. I had rarely felt such a strong sense of place. And that flowed from Wilfred and Garry. The hills, creeks and billabongs belonged to them in a loose but powerful way, because their ancestors had lived here, and because they had walked all over this landscape and knew it so well. Aboriginal people in places like Gunbalanya still go on walkabout, travelling to visit friends and relations – as so many of us do – but also to remind themselves of ancient stories and their landscape. Wilfred and Garry’s sense of belonging in a landscape seemed not to be tied to one particular place, but to the idea of a journey across the countryside. It seemed like an ancient – but not at all primitive – idea, perhaps something that many of us, settled in a very sedentary existence in villages, towns and cities, feel we have lost.

So I had found evidence of the first Australians. I had followed the faint traces of the first colonisers all the way to Sundaland – and Sahul.

And I had met people in Australia who had taught me something about what humans are, passing on knowledge from generation to generation through art, and still feeling the need to roam in the landscape.

3. Reindeer to Rice:

The Peopling of North and East Asia

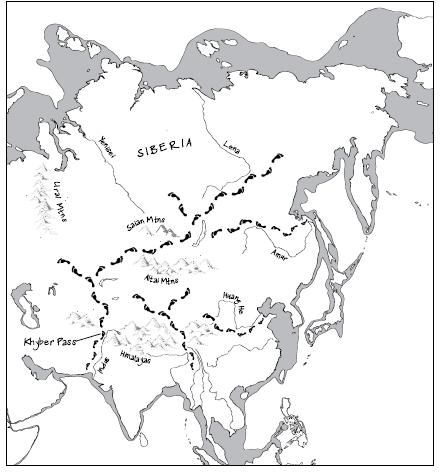

After the initial colonisation of the southern and eastern coasts of Asia (not shown on

this map), Asian genes (mitochondrial and Y chromosome) reveal colonisers spreading

up the rivers, making their way north of the Himalayas and reaching Siberia.

Trekking Inland: Routes into Central Asia

The southern route out of Africa scattered people along the coast from India to South-East Asia and Australia. But what about

the rest of Asia? There was a vast expanse of land to the north and east. Today that land is mainly occupied by two vast countries: Russia and

China. But in the Palaeolithic it was one great wilderness, teeming with wildlife: prime hunter-gatherer territory.

I was on the search for the first Russians and Chinese. How did they penetrate the continent and just how far north would

Palaeolithic technology let them venture? I was also interested in faces, and the origins of characteristic East Asian features,

and this enquiry would take me back to that debate about replacement versus regional continuity, a recent African origin of

modern humans or multiregional evolution.

Analysis of mitochondrial DNA in northern Asia has shown that all the lineages can be traced back to M and N in southern Asia

(see page 101). This means we can be sure that people moved out of Africa, along that southern, beachcombing route, and then

flowed northwards to populate northern Asia.

1

Populations spreading northwards from the South Asian coast could have followed rivers inland – but a massive barrier stood

between South and Central Asia, stretching all the way from Afghanistan in the west to China in the east: the Himalayas.

In

Out of Eden

, Oppenheimer

2

described potential routes around and through this mountainous barrier, allowing access to Central Asia, following

rivers inland. The Indus may have led colonisers up to the Khyber Pass, skirting the Himalayas in the west. Colonisers could

have tracked northwards along the rivers of South-East Asia. If the beachcombers had continued up and along what is now the

Chinese coast, they could have then moved westwards, along what would become the Silk Road, just north of the Himalayas. People

could have also spread in from the west, from the Russian Altai.

Once populations were established north of the Himalayas, the vast expanse of Central Asia and Siberia lay open to colonisation.

Siberia itself is huge, covering about 10 million km

2

and stretching from the Altai and Saian mountains in the south, to the

shore of the Arctic Ocean in the north; from the Ural Mountains in the west, to the Pacific in the east. The environment

here was about as different from the tropics, where early modern humans had flourished, as it could possibly have been. There

would have been many new challenges facing the early pioneers: a lack of plants to eat, extreme cold and sometimes even a

scarcity of wood for building shelters or burning for warmth. Colonising Siberia would have required new adaptations, new

ways of hunting: a whole new suite of survival skills.

Mitochondrial DNA from populations across modern Siberia contains a record of a complex process of colonisation, with a mixture

of lineages from European and Asian branches, presumably relating to incursions from both the west and the south, from modern-day

Mongolia. Genetic diversity is greatest among Altaians, suggesting that modern humans have been in that region the longest.

Unlike the long, thin, rake-like distribution of mitochondrial DNA branches in South-East Asia, which maps so well on to coastal

dispersal from west to east, the branching bush of mtDNA in Siberia gives us less insight into the actual routes into the

icy north.

3

Considering that Central Asia is so huge, the archaeological evidence for early modern human colonisation north of the Himalayas

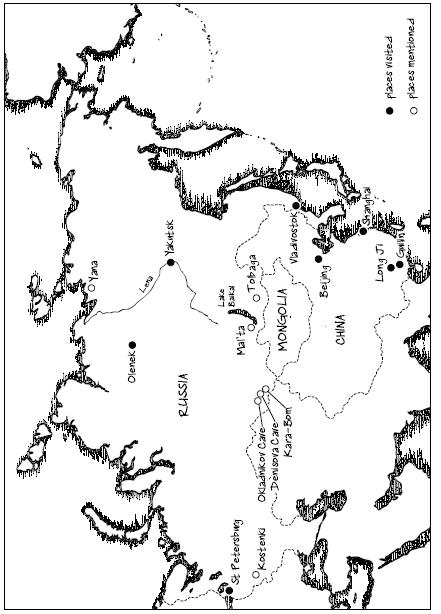

is scarce. The earliest archaeological evidence comes from a site far north of the Himalayas: Kara-Bom in the Russian Altai. Kara-Bom

is an open-air site, situated at the foot of a steep cliff, close to tributaries of the Ursul River. The site was excavated during the 1980s and early 1990s. Digging down through five metres of sediments at the foot of a slope,

the archaeologists found evidence for three phases of occupation. The deepest layer contained Middle Palaeolithic, Mousterian

tools, including Levallois cores and flakes as well as finished tools including points, side-scrapers and knives: it looked like a fairly standard Neanderthal toolkit.

4

In the next layer up at Kara-Bom, the archaeologists found the clear signature of modern humans: early Upper Palaeolithic

tools, including prismatic cores left over from blade manufacture, and plenty of blades, retouched on one or both sides, as

well as end-scrapers, side-scrapers and burins. Above that again were late Upper Palaeolithic tools including microblades.

In the 1980s, archaeologists used conventional radiocarbon dating to age the Upper Palaeolithic layer at Kara-Bom, and reported

a date of about 32,000 years old. In the 1990s the archaeologists used the new, more reliable method of AMS radiocarbon dating,

on charcoal from the microblade layer, and obtained a date of about 42,000 years old.

5

,

4

The animal bones also excavated from Kara-Bom provide us with a good idea of how rich the area was in terms of animal life:

there were bones of horse, woolly rhino, bison, yak, antelope, sheep, cave hyena, grey wolf, marmot and hare; it sounded as if it would have been a good place for the Palaeolithic hunters.

In fact, there is a scattering of Upper Palaeolithic sites in southern Siberia, stretching as far east as Lake Baikal, as

well as a couple further south, in Mongolia.

6

So far, Kara-Bom has produced the oldest date for modern humans in Central Asia, but several other sites in southern Siberia

are nearly as ancient, dating to between 30,000 and 40,000 years ago. Although some are cave sites, most are open-air camps,

like Kara-Bom. These Upper Palaeolithic sites have characteristic stone tools, but also artefacts made from bone, ivory and

antler, as well as deer-tooth pendants. In terms of evidence for art, there’s really not much from the Siberian Upper Palaeolithic.

Just a few sites have produced objects that could be construed as artistic artefacts: a stone disc coloured with red ochre,

a possible carving of a bear’s head on a woolly rhinoceros vertebra and an ivory sphere.

Judging by tools in deeper layers, quite a few of the sites seem to have been used by archaic humans, perhaps Neanderthals,

long before moderns got there. Ted Goebel places the colonisation of southern Siberia by archaic humans in the Middle Pleistocene,

somewhere between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago, with modern humans moving in to occupy the area between 45,000 and 35,000

years ago. Could Neanderthals have still been living in Siberia when modern humans arrived? Dates and ancient DNA results

from Okladnikov Cave in the Siberian Altai suggest that this may have been a possibility. Mousterian tools were found in the

cave, but of course those could have been made by modern humans or Neanderthals. Some researchers suggested that teeth found in Okladnikov Cave, dating to around 40,000 years ago, were Neanderthal, but others

disagreed. There were also some fragments of bone, too smashed up for us to be sure what species they belonged to. But geneticists recently

managed to extract ancient DNA from those bits of bone – and they did indeed turn out to be Neanderthal. This is extraordinary

because it suggests that the Neanderthals penetrated a lot further into Asia than previously thought, and that there may well

have been overlap with modern humans, as in Europe.

7

(We don’t know if those Neanderthals and modern humans ever met each other, though, and this is a question that will be pursued

in the next part, The Wild West: The Colonisation of Europe.)

Although it is clear that archaic humans, including Neanderthals, lived in the mountainous regions of southern Siberia, they

did not seem to get any further north, into the subarctic and Arctic regions. And the first modern humans to live in the area

were also limited to southern Siberia. It appears that these first colonisers were, as Goebel puts it, ‘tethered to places on the landscape’, where there was suitable

stone for making tools and plenty of animals to hunt. There’s no evidence of long-distance trade networks: tools were made

from local stone. In this respect, it’s a similar picture to Europe in the early Upper Palaeolithic. But there is a distinct

difference in the types of tools being made. The stone tools from the early Upper Palaeolithic of Siberia, and from China,

too, are a bit of a strange ‘mixed bag’ when compared with the European toolkits. There are ‘modern-looking’, light-duty tools

like small end-scrapers, borers, points and burins, but there are also very old-fashioned looking tools like side-scrapers,

Mousterian-like points and sometimes even hand-axe type tools. Some archaeologists have argued that this shows a lack of technological

development in isolated large populations, but others have said it can be explained functionally: the toolkits reflect different

patterns of hunter-gatherer subsistence in particular environments. This functional and ecological interpretation also gets

us away from the idea that humans were always on a quest to make ‘better’ tools. Instead, they were making what they needed

to survive in particular place.

8

On the Trail of Ice Age Siberians: St Petersburg, Russia

I travelled to St Petersburg to find out more about Ice Age Siberia. It was mid-spring and the River Neva (‘Nyeva’) had almost

completely broken free from winter ice. Just a few plates of ice clung to its edges and floated like diminutive icebergs under

its bridges.

In a restaurant in St Petersburg I met up with Russian archaeologist Vladimir Pitulko to find out about an exciting site in

the far north-east of Siberia. Until just a few years ago, it was thought that modern humans hadn’t got as far as the Arctic

Circle until after the LGM, around 18,000 years ago. But Pitulko had been excavating a site which suggested that the early

modern human colonisers had adapted to the extreme conditions, and spread further north than any archaic humans had managed,

right into subarctic and arctic Siberia, well before the LGM. The site was called Yana: it was an Upper Palaeolithic site

frozen into the permafrost.

In 1993, geologist Mikhail Dashtzeren found a foreshaft, or spear end, made from woolly rhino horn, in the Yana Valley. (Foreshafts

allow speedy replacement of broken spear points, thought to be a great advantage when hunting large game.) The artefact was

the first sign of a Palaeolithic site eroding out of the permafrost – a site to become known in full as Yana RHS (Rhinoceros

Horn Site). Excavations began some years later, in 2002. The archaeologists found stone tools made from flinty slate, including

side-scrapers and end-scrapers. These are all based on flakes: there is no sign of blade manufacture from Yana. There were

vast quantities of animal bones, mainly reindeer, but there were also mammoth, horse, bison, hare and bird bones. Nearly all

the bones showed signs of scraping. Two further foreshafts were found, made from mammoth ivory, and a bone punch, or awl.

The finds were radiocarbon dated to around 30,000 years ago.

1