The Incredible Human Journey (11 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

So when – and from where – did humans expand out of Africa? Migrations out of Africa may have depended on our ancestors being able to usefully exploit marine resources and spread along coastlines. But those migrations were also constrained and determined by geographic and climatic factors, factors that vacillated with the changing environment of the Pleistocene.

2

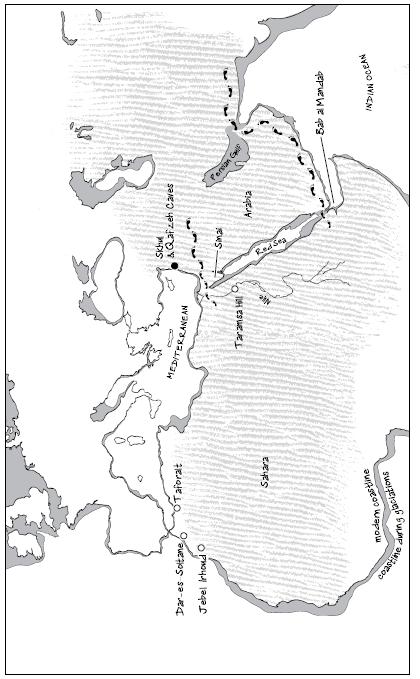

Geographically, at least four routes from Africa to Eurasia seem possible: from Morocco, across the Strait of Gibraltar; from Tunisia to Sicily to Italy; a northern route from Egypt into the Sinai Peninsula, and up into the Levant; and a southern route from Eritrea, across Bab al Mandab (the ‘Gate of Tears’) at the southern end of the Red Sea. All would have involved sea crossings apart from the Sinai route, but, as we have seen, the occupation of Australia, by perhaps 60,000 years ago, would have required a sea crossing.

3

So which of these routes may have been used, given the genetic and archaeological evidence?

As many of these routes suppose a spread out of North Africa, what is the evidence for the earliest modern human presence in that area? In the 1960s the fossil remains of four hominins were discovered in Jebel Irhoud cave, along with Middle Palaeolithic Mousterian tools, in a quarry in Morocco. Animal fossils suggested that these might date to the end of the Pleistocene. Recent uranium series and ESR (electron spin resonance) dates on a juvenile mandible from Jebel Irhoud place the fossil around 160,000 years old.

4

Some researchers claimed that the skulls were Neanderthals, but recent analyses have concluded that, though certainly robust, these people were early modern humans.

5

There are some sites, like Dar-es-Soltane in Morocco, where early modern human fossils were found associated with Aterian tools, and there’s other evidence of modern behaviour, with pierced shell beads found alongside Aterian points at the site of Taforalt in eastern Morocco, dating to around 82,000 years ago.

5

,

6

Routes out of Africa. The trails of footprints indicate the northern and southern routes at either end of the Red Sea.

The dune texture shows the maximum extent of deserts – during glaciations.

There is, however, no actual evidence of any spread of modern humans from North Africa into Europe: it seems that the Mediterranean was a major barrier to expansion and colonisation. The dates of archaeological sites in Europe, as well as genetic studies of modern Europeans, suggest an east-to-west spread, making an exit from East Africa most likely.

7

So that leaves the two routes out of East Africa: a northern route via Sinai, and a southern route across Bab al Mandab. The navigability of these routes would have varied during glacial cycles.

In his book

Out of Eden

, Stephen Oppenheimer discussed the likelihood of each of these routes as an exit point for modern humans from Africa, taking into account the climate and environment at the time.

8

For most of the Pleistocene the northern route out of Africa would have been ‘shut’: the climate would have been cold and dry, and both the Sahara and Sinai deserts would have been impassable. But the Ice Age was punctuated by interglacials, about one every 100,000 years, when the climate temporarily warmed up and the monsoon returned. During these periods, some of what had previously been desert would have turned green. Oppenheimer vividly describes this event as being like a ‘science-fiction stargate’. Sub-Saharan animals would have been able to move into areas that had previously been desert, expanding their range from equatorial regions into temperate zones. African fauna could move up into the Levant through a green ‘environmental corridor’ right through the Sinai Peninsula.

9

We are enjoying an interglacial at this moment: a nicely warm phase that started 13,000 years ago. The last interglacial before this one, the Eemian or Ipswichian, corresponding with OIS 5, started about 130,000 years ago: it seems that the climate was particularly warm and wet between 130,000 and 120,000 years ago.

10

It is also around this time that the first traces of modern humans appear outside Africa, in the form of fossils from the caves of Skhul and Qafzeh, in Israel. It seems likely that the ancestors of these people left Africa by that newly green northern route. We are somewhat trapped here by our own appreciation of geography, our ideas of where continents begin and end. In fact, rather than thinking of these humans as having ‘left Africa’, it is probably better to think of the Levant of 125,000 years ago as an extension of north-east Africa: it was essentially part of the same environment, with the same range of animals, and modern humans were part of that African fauna.

7

,

11

So I made my way to Israel, to visit Skhul Cave. From Tel Aviv, I drove north and followed directions to the place, leaving the main road to enter a canyon called Nahal Mearot (or Wadi el-Mughareh), near Mount Carmel. The valley was framed by great limestone ridges on each side, and there was a series of caves on the southern escarpment. Still following directions, I headed up the valley a little way on foot, and then up the hillside to Skhul Cave. It was an unprepossessing place: small and short, opening on to a flat terrace in front. I could see where spoil from excavations had been piled in mounds, now covered in thorn bushes, just in front of it. I noticed lots of tiny pieces of flint debitage (debris from making stone tools), scattered on the ground in front of the cave.

I sat on the rocks outside the cave and waited for Professor Yoel Rak to arrive. Yoel Rak was an anatomist at Tel Aviv University and a distinguished palaeoanthropologist. As well as working on Pleistocene sites in Israel, he had also worked with Don Johanson and William Kimbel in Ethiopia, finding the first, almost complete, skull of the early hominin

Australopithecus afarensis

.

Yoel told me about the discoveries at the Mount Carmel caves. As with so many sites, the Mount Carmel caves had been found by accident, by British geologists planning a new road and port at Haifa in what was then British Mandate of Palestine. Archaeologist Dorothy Garrod, who later became the first female professor at Cambridge University,

12

arrived to direct excavations, accompanied by palaeontologist Dorothea Bate, from the Natural History Museum in London. The excavations continued from 1924 to 1934. Yoel said that Dorothy was quite a feminist, and that the excavation team had consisted almost entirely of women from the nearby Arab village, but apparently some men had been drafted in when it came to the strenuous job of hand-drilling and lifting slabs of limestone breccia. Yoel pointed out the marks left by the drills on the terrace in front of Skhul Cave. The archaeologists found thousands of Mousterian stone tools in the cemented sediments, and in the lowest layer they discovered ten burials of modern humans.

Just around the corner of the canyon from Skhul, the archaeologists discovered Neanderthal remains in Tabun Cave. Garrod thought that the modern human remains probably dated to around 40,000 years ago, while the Neanderthal bones were more than 50,000 years old. This fitted with the idea at the time that Neanderthals were predecessors to modern humans.

But when absolute dating techniques were applied to the site in the 1980s the modern human burials were found to be much older. ESR dating of bovine teeth from the same layer as the burials produced a date of around 90,000 years.

13

Even more recent dating, using uranium series and ESR on fossil human bone and teeth, and on two animal teeth associated with the burials, indicate that the Skhul burials date to some time between 100 and 130 thousand years ago.

14

After visiting Skhul Cave, I went to see some of the human remains themselves, in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem. To reach them I walked through echoing galleries full of classical sarcophagi, Bronze Age burials and ossuaries, but the bones I was going to see were much more ancient.

There were two of the Skhul individuals in the museum: the bones of a four-year-old child (Skhul I) and those of an adult male (Skhul IV). Both skeletons were incredibly well preserved: more complete and in better condition than many medieval skeletons I have looked at in the bone lab at Bristol – and so much older. Soils on limestone generally make for good preservation of bone, but these bones wouldn’t have survived had they not been buried.

The bones of Skhul IV were arranged just as they had been found by the archaeologists. The body was not carefully laid out as in later burials, straight or bound into a crouched position. The skeleton lay awkwardly, with the legs bent at the hips and knees, and the torso twisted on to its front, with the skull resting higher up, and the arms bent to bring the hands close to the face. There was a flint scraper between the hands. It’s very difficult to know if this was placed in the grave deliberately or whether it was just in the soil that had been heaped on top of the body at burial.

But there were other objects with the Skhul burials that definitely appear to have been associated with the burials, to have been placed in the ground at the same time as the bodies. Skhul V was buried with a boar’s mandible clasped in its arms, and there were also two shell beads in the same layer as the burials.

15

Later in the 1930s, more modern human remains turned up in a cave near Nazareth, called Qafzeh. Initially, seven individuals were found, but when the cave was reinvestigated in the sixties and seventies the remains of a further fourteen individuals were uncovered.

16

One of these, an adolescent, was buried holding deer antlers in its arms, and there were also pieces of worked ochre in the ground with the burials.

14

The two sites at Skhul and Qafzeh represent the earliest evidence anywhere of burial. Placing grave goods in the ground with the body is further evidence of ritual, and a spiritual dimension to these people’s lives. Like the traces of art and ornamentation from South Africa, we seem to be seeing something here which implies modern ways of thinking and behaving: an approach to life and death that seems somehow familiar to us. Although we can’t know what these objects signified, we can assume they meant

something

to the people who placed them in those graves around Mount Carmel all that time ago. It is tempting to imagine that the inclusion of personal ornaments and animal remains might even imply some kind of belief in an afterlife.

But after those burials at Skhul and Qafzeh, traces of modern humans in the Levant disappear, for around 50,000 years. I asked Yoel Rak what he thought had happened. He said it was difficult to prove that people had actually disappeared from the region. They might have stopped burying their dead. There are no more anatomically modern bones, and no more pierced shells, for a long time. And as the stone tools at Skhul were very basic, Mousterian tools, in fact exactly the same as Neanderthal technology, the presence of modern humans could not be demonstrated through tools alone, that is, until more sophisticated technology appeared in the Levant, around 45,000 years ago. Perhaps the evidence is there but hasn’t been found yet. But maybe that absence is real, and Yoel believed that the disappearance of modern humans from the Levant, perhaps 90,000 years ago, could be explained by looking at what was happening to the climate and the environment at the time.