The Italian Boy (18 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

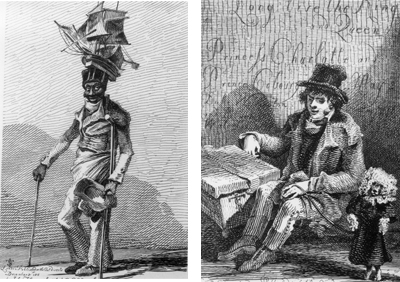

Black Joe Johnson; Charles Wood and his Learned French Dog, Bob; an aged “sledge beggar”; and the Dancing Doll Man of Lucca; all sketched by J. T. Smith for his compendia of street people,

Etchings of Remarkable Beggars,

1815, and

Vagabondiana,

1817.

But according to Charles Knight, “the high and rushing tide of greasy citizenry” needed the color and spectacle that poor folk such as these—even the idle or the impostor—brought to city streets. The architectural splendors of London were many; but most streets were notable for their monotony and dreariness (a look that the Victorians were to delight in defacing with large, florid buildings, from the 1860s on). Away from the main streets, deep gloom pervaded: Joseph Sadler Thomas complained that after sundown, Covent Garden market was hard to penetrate and patrol effectively since there was just one, centrally placed lamp. He could hardly see his hand in front of his face, he said: “I act in the dark.”

4

Ornamentation had been severely limited by the 1774 Building Act—which imposed higher standards of house construction and fireproofing at the expense of architectural variety—and aside from the occasional flourish of stucco and portland stone, street after street was lined with brick buildings that were blackened by smoke and filth; some had even been painted black—a Georgian fancy. Houses were rarely higher than three stories, and in certain areas by the 1830s the products of the eighteenth-century building boom were proving unable to cope with the sheer numbers of people cramming into them. The squalid frowsiness of many parts of east and central London were well known (“foetid localities … infected districts,” proclaimed the architect Sydney Smirke), but the Georgian terraces of the wealthy west were also seen as dismal regions—dark, featureless, cheerless canyons of blank brick wall.

5

Nevertheless, by 1823, 215 miles of London street had been lit. The flickering glare of gaslight brought a theatrical quality to many central streets, an effect enhanced by the presence of music (players strolled the streets of the West End, and one Italian band seems to have taken up a regular perch in Portland Place, just north of Oxford Circus). The stagelike quality only enhanced the strange appearance of the crowds. Even the tide of greasy citizenry could provide a spectacle to the onlooker, a cavalcade of images not unlike the panoramas, dioramas, cosmoramas, and georamas that were enjoying such popularity in new, purpose-built venues. For writer Thomas De Quincey, Londoners passing along the street looked like “a masque of maniacs, a pageant of phantoms”; in a short story, Edgar Allan Poe described the giddy fascination of watching London’s “tumultuous sea of human heads” rolling by as the hero attempts to sort them into “types”; while in 1837, a doctor writing about the effect of the city on human health described Londoners as appearing distracted, pallid, shattered, sallow-complexioned, and “paralytic of limb”—puppets or automata moving to some invisible mechanical force.

6

George Scharf captured many of London’s street characters throughout the 1820s and 1830s, including itinerant vendors of many nationalities and an Italian “image boy,” second from left.

* * *

A huge unknowable,

a subject that greatly perplexed those who looked into the question of vagrancy, was the proportion of beggars who were frauds; even a central London magistrate of long standing admitted that he could rarely distinguish someone who was genuinely out of work and hungry from someone who was quite capable of making a living but instead preyed on public sympathy.

7

Appearance was an increasingly unreliable gauge: continental visitors noted that the English tended to wear clothes that did not necessarily reflect their class, and, from the start of the nineteenth century, the English working classes had reportedly shown a new interest in self-adornment.

8

There was a vast trade in secondhand clothing; many householders would dress their servants in their castoffs, further eroding class distinctions in dress. To add to the confusion, thieves were known to adopt the type of clothing that parish constables or local firemen wore, in order to loiter near or enter a house to commit a burglary unchallenged. Sometimes, only the shabbiness of a garment would mark the pauper, say, from a tradesman or clerk: a policeman reported that his decision not to arrest a group frequently seen loitering in the Bond Street area had been taken because “they are too well-dressed to be apprehended under the Vagrant Act.”

9

Journalist John Wade complained that the city dweller “is everywhere pestered with clamours, and his feelings lacerated by the spectacle of real or fictitious suffering, which ought ever to be excluded from his sight.”

10

Wade believed that virtually all London beggars were fakes; many people agreed with him. Another type of compendium sprang up claiming to detail the various ruses that beggars used to fool the public and providing a glossary of street slang used by this emerging tribe of other Londoners. The anonymous pamphlet

An Exposure of the Various Impostures Daily Practised by Vagrants of Every Description

appealed to the cynic who wanted to be bolstered in the view that all beggars were impostors; it also tapped into the apparently large market discovered by James Hardy Vaux, a twice-transported thief and fraud whose

New and Comprehensive Vocabulary of the Flash Language

was published in 1819, and by journalist and comic author Pierce Egan, whose

Life in London

tales had translated the slang of the criminal and sporting fraternities.

11

An Exposure of the Various Impostures,

for example, reveals that “Lurkers” have fake documentation showing loss by wreck, fire, accident, and so on; typical scams include a Fire Lurk, a Sick Lurk, a Deaf & Dumb Lurk, a Weaver’s Lurk. “High-flyers” are begging-letter writers. “Cadgers on the downright” beg from door to door, while “Cadgers on the fly” beg from passersby. A “Shallow Lay” stands about in rags on cold days, and “Screevers” chalk on the pavement such piteous appeals as “Hunger is a sharp thorn and biteth keen” or “He that pitieth the poor lendeth to the Lord, and He will repay,” while assuming a mournful look to fool the “Flat”—the dupe, or mug. Loud groanings and lamentations were required in order to be heard over the roar of daytime traffic. (Traffic noise could be so loud that ordinary conversation was often impossible on main streets.) Ann Taylor, in her thirties, was found groaning on a doorstep in Red Cross Street, Barbican, having apparently just miscarried; when a police officer discovered that the bloody matter in her lap was a sheep’s liver, he attempted to arrest her, recognizing her as the woman who had staged a fit outside the Dicity in Red Lion Square and received bread, cheese, and five shillings from passersby. Jane Weston was sentenced to three months’ hard labor for playing the part of a starving woman with nine children; the infants were hired, and two accomplices impersonated benevolent society ladies, to provoke others into almsgiving. James Prior spent fourteen nights in jail for acting the part of a pilgrim unable to continue his journey to Canterbury without money.

12

John Wade claimed that he had seen a beggar chewing soap in order to produce a more convincing fit, while J. T. Smith wrote scathingly of Italian boys’ “learned mice and chattering monkies” and recalled seeing an Italian throw his mice at a terrified nursery maid who had refused to give him any money.

13

“Walking advertisements” as rendered by George Scharf

Despite widespread concern with fraud, criminal convictions were a hit-and-miss affair, even after the passage of the Vagrancy Act. The Parliamentary Select Committee convened in 1828 to consider the inadequacies of the old methods of policing the capital was told that it was well known that two of the four justices of the peace who sat at Great Marlborough Street magistrates office never convicted anyone of vagrancy if it was a first offense, even though they had the power to do so.

14

In 1827, the committee heard, 196 of the 429 vagrants arrested and brought to Great Marlborough Street were instantly discharged, much to the anger of the arresting constables. (Figures such as these cannot give a clear indication of the true level of vagrancy in the city, since many vagrants—most, perhaps—were never arrested in the first place.) By 1832, however, imprisonment figures for vagrancy had risen significantly, suggesting that the New Police were more active in apprehending and/or more persuasive before the magistrates: the number of London vagrants committed to prison rose from 2,270 in 1829 to 6,650 in 1832.

Still, many beggars or “disorderly” or “suspicious” characters escaped arrest because of both “old” police and New Police inactivity, or officers’ genuine fellow feeling for the street poor, or their fear of attracting an angry crowd during an arrest; other beggars benefited from the territorial disputes between the New Police and the medieval watch system that persisted in the City of London until 1839. Thus magistrate Peter Laurie, who loathed the Metropolitan Police, advised the City aldermen to keep driving any unwanted characters found in their area through the Temple Bar in Fleet Street, across the City border for the Metropolitan force to deal with, since, Laurie claimed, he had heard that West End magistrates had advised the driving of the idle and itinerant over the boundary for the City to cope with. Policing the poor had become a game of “tennis ball,” according to one City alderman. It was a spectacle that certain Londoners came to the Temple Bar to watch on a regular basis on a mild evening, enjoying the dance of pursuit and escape performed nightly between the police and the criminals.

15