The James Bond Bedside Companion (10 page)

Read The James Bond Bedside Companion Online

Authors: Raymond Benson

A slightly revised version of James

Bond's coat

of arms,

based

on the original coat of arms designed at Fleming's request

by the Rouge

Dragon at the College of Arms for ON HER MAJESTY'S SECRET SERVICE. (Illustration

by

James Goodner.)

On February 4, 1962, the

Sunday Times

published in the first issue of the new color supplement a James Bond short story by Fleming entitled "The Living Daylights." The

Daily Express,

which had been serializing the novels and held the rights to the comic strip, was incensed about this, but Fleming managed to smooth things over once he got back to England.

THE SPY WHO LOVED ME

was published in April, with a lovely Richard Chopping jacket picturing a Wilkinson dagger, red carnation, burnt paper and a burnt matchstick. On the title page, Fleming added a co-author under his own name: Vivienne Michel, the heroine of the story. In a preface to the American edition, Fleming stated that he found the manuscript on his desk at his office one day, spruced it up, and submitted it for publication. But he didn't pull anyone's leg. The world knew it was Ian Fleming's novel. The author was expecting mixed reviews for this one, and got them. In fact, Fleming was quite distressed at several violent attacks (one on television) for what some critics called the "pornographic" episodes of the heroine's early life before Bond enters the story. As a result, the book was banned in some countries, including the paperback edition in England for a few years. The

Times

called it a "morbid version of 'Beauty and the Beast,'" and

The Listener

described it as being "as silly as it is unpleasant." More women seemed to like it, however. Esther Howard in

Spectator

found it "surprising," adding that she liked "the Daphne du Maurier touch" and preferred it that way, but doubted that real fans would. Because of the poor reception of the book in England, Fleming stipulated to Eon Productions and Glidrose that only the title of this particular novel could be used by the film makers when the time came to bring

THE SPY WHO LOVED ME

to the screen. In America, reviewers were cool toward the book as well. Anthony Boucher wrote that the "author has reached an unprecedented low." This was the last Bond novel to be published by Viking Press. Fleming switched to New American Library and NAL immediately began a mass paperback campaign to promote the books, all with uniformly designed covers.

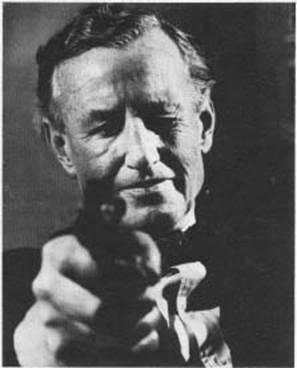

Ian Fleming camping up the Bond image. (Photo by Loomis Dean,

Life

Magazine, © Copyright 1966 by Time, Inc.)

That summer, with his health fluctuating between

good and bad, Fleming decided he would send Bond to Japan for his next novel. The author was anxious to be reunited with his friend Richard Hughes, the

Sunday Times

representative in the Far East. Fleming had met the Australian in 1959 during the THRILLING CITIES tour. For twelve days, Fleming was guided through Japan by Hughes and Torao "Tiger" Saito, the editor-in-chief of a distinguished annual called "This is Japan," published by the Asahi Shirnbun. Fleming was to show his gratitude to the two men by creating in their images the characters of "Dikko" Henderson and Tiger Tanaka.

Fleming received considerable exposure in American magazines that summer. The short story, "The Living Daylights," was published in the June issue of

Argosy

under the title "Berlin Escape." The August 10 issue of

Life

featured an article on Fleming. The photographs, taken by Loomis Dean, showed the author camping it up as he posed with guns, playing cards, and a Bentley. Other American magazines, especially men's publications, began featuring Bond serializations. DOCTOR NO was published in

Stag

magazine with the inappropriate title, "Nude Girl of Nightmare Key."

A couple of years later,

Stag

published

THE SPY WHO LOVED ME as "Motel Nymph"!

Playboy

,

though, did a much classier job with serializations of all the remaining Bond novels beginning with ON HER MAJESTY'S SECRET SERVICE. The appearances of Fleming's work in

Playboy

did much to perpetuate the Bond/Playboy image in the early days of the author's fame in America.

Around this time, Fleming's portrait was painted by his friend Amherst Villiers, whom he had known since the thirties. Villiers had designed superchargers (James Bond had an Amherst Villiers supercharger in his Bentley), and had taken up painting as a hobby. Fleming bought the portrait, and it was used as a frontispiece in a limited edition of ON HER MAJESTY'S SECRET SERVICE.

On October 7,

Dr. No

premiered in London, and was a resounding success. Sean Connery was immediately accepted by the public as James Bond, and Ian Fleming seemed to like it as well. His words were, "Those who've read the book are likely to be disappointed, but those who haven't will find it a wonderful movie." Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman began planning the next film.

I

n January and February of 1963, Fleming wrote YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE at Goldeneye. The original manuscript was 170 pages long, and was the least revised of the novels. The book ended with another cliffhanger: James Bond has amnesia and is lost somewhere in Russia after leaving Japan.

In April, ON HER MAJESTY'S SECRET SERVICE was published. There was a limited edition of 250 copies, each numbered and signed by the author. The regular edition featured yet another Richard Chopping painting on the jacket, which showed an artist's hand completing a design of Bond's coat of arms (complete with the Bond family motto, "The World is Not Enough"). Reviews were ecstatic. The

Times

called it "perfectly up to snuff, well-gimmicked, well-thrilled, well-jacketed." New American Library published the book a few months later, and it topped the

New York Times

best seller list for over six months. R. M. Stem called it "Solid Fleming. . . Mr. Fleming is a story teller of formidable skill."

In May,

Dr. No

was released in the United States. Bosley Crowther in the

New York Times

thoroughly recommended the film, and it looked as though Eon Productions, in winning the American audience, truly had a successful investment. The second film,

From

Russia With Love

, was almost complete, and Fleming had visited the set in Istanbul. He went mostly to see his friend Nazim Kalkavan again, but also because he was curious about what they were doing to his favorite book.

From Russia With Love

premiered in October in England, again to very favorable reviews. Ian and Anne Fleming threw a party for the cast and crew, but the author felt too ill to enjoy himself properly. He finally went upstairs to his room while the party continued.

In November, a James Bond short story entitled "The Property of a Lady" was published in a book called

The Ivory Hammer: The Year at Sotheby's.

Sotheby's specially commissioned Fleming to do a story concerning an auction. It later appeared in

Playboy

magazine. Jonathan Cape finally published THRILLING CITIES that November as well, with a surrealistic painting of Monte Carlo by Paul Davis on its jacket. The book received mixed reviews in both England and America (the American edition was published by NAL).

On November 19, the THUNDERBALL court case finally began. Not only was Fleming being sued by McClory for plagiarism and false attribution of authorship (Whittingham had dropped out as plaintiff due to financial difficulties), but Ivar Bryce was accused of injuring McClory as a false partner in Xanadu Productions. It was an extremely complicated case and the details are still controversial today. The attorneys for Bryce and Fleming felt that they had a case, as did their friend, Ernest Cuneo. In an affidavit on file in London, Fleming stated that Cuneo had "scribbled off" the basis of a suggested plot for the film. This draft was dated May 28, 1959 and Cuneo assigned all rights in the document to Bryce for the sum of one dollar. Fleming acknowledged this original source in the published copies of THUNDERBALL—the book is dedicated to Ernest Cuneo, "Muse." But it was soon apparent that McClory had a strong case, and Jack Whittingham's testimony would be in his favor. Additionally, a letter dated November 14, 1963, from Fleming's solicitors admitted that the THUNDERBALL novel did reproduce a substantial part of the copyrighted material from the scripts in question.

During the three weeks of the trial, Ian Fleming was not well, although he was in the courtroom every day. His friend Bryce was worried about him, afraid that the stress could possibly cause another heart attack. After days of wrestling with this worry and with the ultimate realization of how weak their case actually was, Bryce decided to throw in the towel rather than watch his friend endure the days to come. After consulting with his counsel and with Fleming, Bryce asked for a settlement McClory was to put forth his demands. In December, the case was settled out of court. McClory would have "no further interest" in Fleming's novel, but publishers were to add the line "This story is based on a screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham, and the Author" to the title page in subsequent editions. McClory was assigned the copyright to the "The Film Scripts" and the film rights to the THUNDERBALL novel for a consideration paid to Fleming. In addition, Jack Whittingham received a sum of money, and Ivar Bryce paid McClory damages as well as the court costs for all participants. John Pearson claimed that the total cost for the case was estimated at £80,000. (Whittingham afterwards issued a writ against Fleming, but this action died when Fleming himself passed away a few months later.)

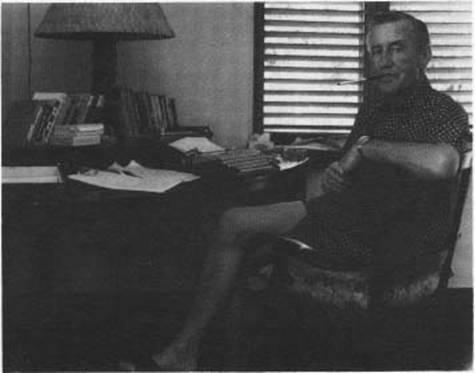

Ian Fleming, taking a pause from writing YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE in 1963 at Goldeneye. (Photo by Mary Slater.)

1964

was the beginning of what could be called "the spy boom." For the next three or four years, secret agents were definitely marketable, and the media began overexploiting the genre. Ian Fleming's creation was undoubtedly the catalyst, and imitations appeared almost overnight. His books had sold an estimated 30 million copies worldwide by the summer, and it looked as if the phenomenon would never let up.

Television was getting into the act as well. Producer Norman Felton had approached Fleming a couple of years earlier about writing a spy series for TV (the CBS deal had fallen through by 1962). Fleming wouldn't commit to the project, but supposedly gave Felton the names for his leading characters: Napoleon Solo and April Dancer. These characters would be featured on the long-running TV series, "The Man From U.N.C.L.E." Other series with spy formats followed: "I Spy" (1965) with Robert Culp and Bill Cosby; "Mission Impossible" (1966); "Honey West" (1965) with Anne Francis; and of course, "The Avengers," which began on British TV in 1961. "Dangerman," with Patrick McGoohan, ran as a half-hour show in Britain in 1960, but was expanded to a full hour in 1965. In the United States it was called "Secret Agent." Motion picture studios began spawning James Bond imitations and spoofs, most notably the two

Man From U.N. C.L.E

.

films,

To Trap a Spy

(1964) and

The Spy With My Face

(1966). Harry Saltzman produced a series of adaptations of Len Deighton novels, starring Michael Caine as Harry Palmer. These were

The Ipcress File

(1964),

Funeral in Berlin

(1966), and

Billion Dollar Brain

(1968). Dean Martin became Donald Hamilton's Matt Helm in

The

Silencers

(1966) and two others. James Coburn created an interesting character in Derek Flint in

Our Man Flint

and

In Like Flint

(1966 and 1967).

Modesty Blaise

(1966) featured a female agent played by Monica Vitti.