The James Bond Bedside Companion (13 page)

Read The James Bond Bedside Companion Online

Authors: Raymond Benson

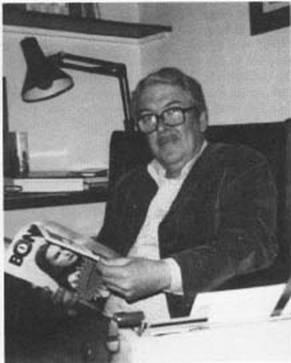

Celebrated British writer, Kingsley Amis, caught reading an issue

of

Bondage

Magazine (published by the James Bond 007 Fan Club). Amis was the author

of

COLONEL SUN

(using the pseudonym Robert Markham) and

The

James Bond Dossier.

(Photo by Raymond Benson.)

In October 1966,

Life

magazine published a two-part serialization of John Pearson's

The Life of Ian Fleming

and ran a photograph of Ian Fleming behind the wheel of a Bentley on the cover of the October 7 issue. The book was published the same month, and remains the definitive biography of Fleming.

While Eon Productions was busy making

You Only

Live Twice

, another James Bond film was in production. Charles K. Feldman, who had bought the rights to CASINO ROYALE from Gregory Ratoff's widow, had finally begun making the picture. At first, Feldman intended to make a serious Bond film and even attempted to interest Broccoli and Saltzman into co-producing. When Feldman was turned down, he decided, at the suggestion of several writers, to make a James Bond spoof. Many writers worked on the script, some uncredited, including Wolf Mankowitz, John Law, Michael Sayers, Ben Hecht, Terry Southern, and Woody Allen. The film also had five directors. Needless to say,

Casino Royale

,

released in April of 1967 by Columbia Pictures, was a mess. There are a few funny bits in the film, which starred Peter Sellers, Ursula Andress, David Niven (as "Sir" James Bond), Orson Welles, Woody Allen, and a host of guest stars including William Holden, John Huston, and Deborah Kerr. But mostly, the plot was confusing and many of the gags never worked.

Casino Royale

,

in all fairness, shouldn't be considered a James Bond film.

The official Bond was back in the summer of 1967 when

You Only Live Twice

was finally released. It was the first film to totally throw out Ian Fleming's story, and illustrates the increasing outlandishness of the series. James Bond was disappearing as a character, and the sets and gadgets were taking over. In terms of spectacle, however,

You Only Live Twice

was impressive. The production values of the films showed no signs of sagging.

Sean Connery made it clear that

You Only Live Twice

was his last James Bond film. The producers

were then forced to begin searching for an actor to

replace him in their next project,

On Her Majesty's Secret Service.

In the spring of 1968, a new James Bond novel was published, written by Robert Markham. Titled

COLONEL SUN

and published by Jonathan Cape in England (and by Harper and Row in the United States), it featured Salvador Dali-like jacket art by Tom Adams. Robert Markham turned out to be a pseudonym for Kingsley Amis, who had

written

The James Bond Dossier.

It was Glidrose's original intention that other writers would have shots at writing Bond books, but they would all use the same pseudonym to avoid confusion. The book received mixed reviews in both countries, mainly because the style was so different from the Fleming books. The

Sunday Times

said that "Mr. Amis is an extremely gifted novelist," but went on to say that James Bond was so personal to Fleming that Amis' work "doesn't ring true." But

The Listener

defended the work, saying that Ian Fleming's "inheritance has been well and aptly bestowed. . . fast-moving action, a rather superior Bond-maiden, violence, knowledgeableness about guns, golf and seamanship. . . Good dirty fun." Kingsley Amis himself considered it a compliment that an American fan wrote and asked him to confirm the rumor that

COLONEL SUN

had been based on drafts and notes which Ian Fleming had left behind. (It wasn't)

COLONEL SUN

seemed to be a misfire at the time, although in retrospect it is a very admirable novel. Because of the somewhat poor reception of the book, Glidrose was silent for quite a while.

A film version of

Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang,

produced by Albert R. Broccoli, was released in 1968. Containing a musical score and featuring Dick Van Dyke, it was only moderately successful.

In October, it was announced that an Australian model with no previous acting experience was to be the new James Bond. George Lazenby, a handsome but curiously naive-looking man, was cast opposite Diana Rigg, who played the woman James Bond marries in

On Her Majesty's Secret Service.

Lazenby, suddenly thrust into the limelight of show business, wasn't accustomed to spending most of his free time attending press and publicity functions. In an interview for

Bondage

magazine (published by the James Bond 007 Fan Club), Lazenby also claimed that others treated him as an inferior on the set. As a result of these experiences, some time before the film's release in December of 1969, Lazenby announced that he

was not going to make any more James Bond films either. The producers, angry that he had announced this fact prior to the film's opening and that he had broken his contract, began to downplay Lazenby in publicizing the film.

On Her Majesty's Secret Service

was the first Bond film not to be a runaway success. Lazenby wasn't received well by the critics or the public, and the film reverted to the more serious, less gadgety format of the early Bonds. It also had a downbeat ending with Mrs. James Bond being shot to death, as in the novel. The film finally broke even two years later, and has since been profitable and in retrospect, it is actually one of the best films in the series.

O

n January 1, 1970, the BBC presented a documentary on Ian Fleming for their

Omnibus

series. The program was produced by Kenneth Corden, and John Pearson was the research advisor. The documentary featured many interviews with Fleming's friends and colleagues including Kingsley Amis, Henry Brandon, Cyril Connolly, Noel

Coward, William Plomer, and Col. Peter Fleming. Also featured were clips from the recently released

On Her Majesty's Secret Service

, as well as scenes from earlier films. The program was repeated two years later.

With George Lazenby out of the running, Broccoli and Saltzman were forced to find another James Bond. For a while, it was reported that the producers were considering such American actors as Burt Reynolds and John Gavin. But David Picker, then head of United Artists, believed Sean Connery could be persuaded to return to the role. Picker felt that it was Connery audiences wanted to see, not just any James Bond. As reported in Steven Jay Rubin's book,

The James Bond

Films

, Picker flew to London and offered Connery one of the most lucrative deals in cinema history—a salary of one-and-a-quarter million dollars (which Connery subsequently donated to the Scottish International Education Trust). In addition, United Artists agreed to back two films of Connery's choice that he could either act in or direct. (One of these films,

The Offense

,

was made in 1972 and was again directed by his friend, Sidney Lumet) Connery accepted, with the additional stipulation that he would be paid an additional $10,000 for every week that went over the scheduled eighteen weeks of shooting.

Diamonds

Are Forever

,

released in December of 1971, was one of the biggest grossing Bonds, yet Sean Connery appeared once again as 007, looking quite a bit older and heavier. But the audiences loved him and screamed for more. But Sean Connery had signed on a one-picture basis only. He was definitely not going to make another James Bond film. So the producers went back to the drawing board once again.

Roger Moore, an admired British actor best known for his television series

(The Saint

,

The Persuaders)

and light comedy roles, was chosen to star in

Live and Let Die.

Moore, it is said, was originally the producers' choice after Sean Connery. Moore was certainly a more experienced actor than George Lazenby, and he added a style and sophistication to his characterization of Bond that was quite different from Connery's interpretation. In a way, the style of the Bond films was changed to accommodate his characterization. In the Bond films of the seventies, comedy was emphasized more and more, until they became a different sort of animal altogether from the early films, and especially from Ian Fleming's novels.

Audiences and critics alike accepted Roger Moore as James Bond when

Live and Let Die

was released in the summer of 1973. Its box-office success ensured the future of the series, and Eon Productions began planning its next film.

A new rash of toys and by-products flooded the market as a result of the film. There was a James Bond 007 Tarot Game manufactured by U.S. Games Systems, Inc., based on the one used in the film. There were more trading cards, and Corgi Toys sold miniature Bond automobiles and the like. A new generation was out there for the merchandisers to tap.

In August,

James Bond—The Authorized Biography of 007,

was published in England by Sidgwick & Jackson, and in the United States by William Morrow & Co., Inc. It was written by John Pearson, Fleming's biographer. The idea for such a book came from William Armstrong, then head of Sidgwick & Jackson. Glidrose Publications (the name was changed from Glidrose Productions in September, 1972) shared the copyright on the book with Pearson. Pearson was surprisingly successful at making this fictional biography convincing. The premise is that Ian Fleming actually

knew

a James Bond in the Secret Service, and that the Service had authorized Fleming to write the James Bond "novels" so that their enemies would believe that Agent 007 was a fictional character! (Of course, the real James Bond's exploits were not as glamorized as Fleming wrote them.) In the book, John Pearson "interviews" James Bond at age 53, and Bond relates his entire life story, embellishing brief references to his early life which Fleming put in the books. Though it's not an "official" James Bond novel, it stands as one of the most interesting and enjoyable works pertaining to the cult.

The first James Bond 007 Fan Club was started that year at Roosevelt High School in Yonkers, New York, by two students, Richard Schenkman and Bob Forlini. Initially, the members were just a few of their friends. In the summer of 1974, they put out a club magazine, called

Bondage

,

and since then, the club has grown considerably. Forlini eventually dropped out, leaving Schenkman to run the club himself.

Bondage

's

first issue was mimeographed, the pages stapled together. Now it is a slick printed magazine with a glossy cover. Today, the fan club has about 1,600 members in the United States and abroad, mostly male. The average age is twenty-one, but Schenkman claims that since

Playboy

wrote about the club in the late seventies, the age has risen to twenty-five. Eon Productions was originally supportive of the club and Cubby Broccoli agreed to an interview in 1978. But since then, the club has not been on the best of terms with the film company for reasons about which Schenkman can only speculate. In

Bondage

No. 5, he published an interview with George Lazenby. In

Bondage

No. 6, he published an interview with Kevin McClory. Neither article probably pleased the film producer. Nevertheless, the club is thriving, and the magazine is member-supported. At the back of this book is an address to write for more information about the James Bond 007 Fan Club.

In December of 1974, United Artists released

The

Man With

the Golden

Gun

,

starring Roger Moore again as Bond, and Christopher Lee as Scaramanga. The film, one of the weaker of the series, did fairly well internationally, but it had a poor reception in America and in England. Around this time, it was reported, Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman were not on the best of terms. They had more or less taken turns producing the last two films. Saltzman had gone on location for most of

Live and Let Die,

and Broccoli had taken more control of

Golden Gun.

Now that the new film was out, Harry Saltzman decided to leave. It was rumored that he needed capital for a private venture, and he sold his share in Danjaq, S.A. (the Swiss company made up of Eon Productions and United Artists) to United Artists. Danjaq, S.A., then, became Albert R. Broccoli (Eon Productions) and United Artists.