The James Bond Bedside Companion (52 page)

Read The James Bond Bedside Companion Online

Authors: Raymond Benson

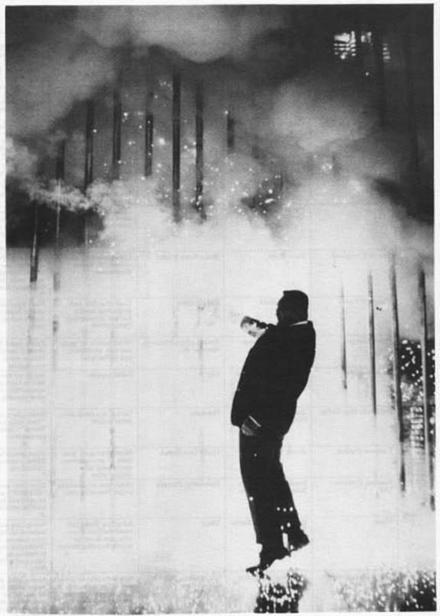

Oddjob "blows a fuse." The late Harold Sakata as the Korean bodyguard in

Goldfinger

. (Photo by Loomis Dean, Life Magazine. © Copyright 1964 by Time, Inc.)

T

itle credits designer Maurice Binder told a Museum of Modem Art audience in 1979 that he had fifteen minutes before a conference to come up with a design for the opening of the first James Bond film,

Dr. No.

He scribbled down his ideas and rushed to the meeting. The result was the famous gun-barrel logo which begins every 007 picture in the Eon Productions series. First, the United Artists logo silently appears on the screen. Next the audience hears (very loudly) the John Barry orchestra blasting out "The James Bond Theme," as two white circles roll onto the screen from the left, dancing about until they converge. The circle enlarges and suddenly the audience is looking through a gun barrel. From the right walks James Bond, who turns and fires a gun at the camera. The action freezes and a red wash flows down from the top of the screen. The figure fades out to a white circle again. The circle moves around the screen as if it's searching for a place to settle; when it finally stops, the circle disappears and we are at some exotic location. Following this sequence, another traditional element—the pre-credits sequence—is played out until the main title credits appear and the theme song of the picture is heard.

Adherence to a traditional formula created by the films' producers, Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, is a major reason for the success of the Bond series. This formula has proven that James Bond is a very marketable item, and Eon Productions, Ltd., formed by Broccoli and Saltzman back in 1961 to make the films, is one of the most successful operations in the history of cinema. To date, there have been thirteen James Bond films (excluding

Casino Royale,

produced by Charles K. Feldman in 1967, and

Never Say Never

Again

, produced by Jack Schwartzman with Kevin McClory as executive producer in 1983) and each has made money. The only film that was not a runaway

hit was

On Her Majesty's Secret Service

(1969), but it has since proven to be financially successful. This film fell short precisely because it broke several traditions, especially in its concept

The formula fundamentally follows this outline: James Bond (played by a star that audiences admire) goes to investigate mysterious goings-on involving intemational security; finds a villain (usually with a superstrong henchman/sidekick) in his own super-technological headquarters; infiltrates the headquarters and eventually blows it up with the help of gadgetry, a military force of good guys and/or his own resourcefulness. The formula, begun in the first film,

Dr. No,

was more or less repeated in

Goldfinger, Thunderball, You Only Live Twice, Diamonds Are Forever, Live and Let Die, The Man With the Golden Gun, The Spy Who Loved Me, Moonraker,

and

Octopussy.

John Brosnan in

James Bond in the Cinema

considers

Goldfinger

the best film in the series, which was at its peak at the time, with all the elements of the formula working in top form. After

Goldfinger,

Brosnan notes, the producers were faced with the problem of topping it and were forced to repeat the formula, disguised by bigger budgets, more exotic locations and set-pieces, more gadgets, more slapstick comedy, and more special effects.

THE PRODUCERS

A

lbert R. Broccoli was born in New York in 1909 and spent the early part of his life working for relatives in a number of different jobs, including one as an assistant undertaker (which explains the profusion of coffin/undertaker jokes in the Bond films). He became a tea boy at 20th Century-Fox studios and rose in the ranks to assistant director. After World War II he cofounded Warwick Films and coproduced such features as

The Red Beret

and

Zarak

(both directed by Terence Young),

Hell Below Zero

(written by Richard Maibaum),

The Black Knight, Cockleshell Heroes,

and

The Man Inside,

all in the 1950s. Broccoli became interested in the James Bond novels, but when he inquired about purchasing film options, he discovered that Harry Saltzman had already done so.

Saltzman was born in Quebec in 1915 and had an early vaudeville and circus background. He lived in France for quite a while, working in theatrical circles. After World War II, he moved to the United States and

found work in television. Saltzman successfully co-

produced John Osborne's

Look Back in Anger

on

Broadway, ultimately co-producing the film as well. Forming a partnership with John Osborne and director Tony Richardson, Saltzman made two more superb British films,

The Entertainer

and

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning

. After the latter, Saltzman left the partnership, discovered the Bond novels, approached Ian Fleming and bought the rights to the entire series, excepting only CASINO ROYALE (which had already been sold and was then owned by Charles K. Feldman),

and THUNDERBALL (

which came under litigation as soon it was published in 1961). Shortly before the option on the books ran out, Saltzman met Broccoli and they formed Eon Productions, Ltd.

Dr. No

was their first James Bond film.

From the very beginning Broccoli and Saltzman had total control over the Bond pictures. They dictated to what degree the screenplay should reflect the novel, decided what elements should go into the film and approved final casting. It was their decision to make the films more humorous than the novels. It took a couple of films to find the right mixture of seriousness and humor to suit them, but once they did, the formula was set. Convincing Broccoli and Saltzman to depart from the formula would be no easy task for a director or script writer.

Broccoli and Saltzman also dictate the amount of sex and violence in the films.

Dr. No

, the most violent of the pictures, featured the first and only instance in which 007 shoots a man in cold blood. After

Dr. No

, the violence was toned down considerably, and by the time

Goldfinger

rolled around, action scenes were stylized and bloodless. Audiences are never asked to watch gory bloodletting in the Bond films. The same applies to sex. The first three films offered several seduction scenes, and Bond was certainly something of a male chauvinist by today's standards. After

Goldfinger

, however, sex in the films became basically voyeuristic, limited to shots of lovely women in scanty bikinis or evening gowns; the camera almost always fades out as Bond's seduction of the heroine begins. The Bond films are family films, Saltzman liked to stress.

Broccoli and Saltzman's formula envelops the idea of making the films total cinema, i.e., high standards of production, lots of action and breathtaking stunts, on-location shooting in exotic places around the world, exaggerated sound effects, and exhilarating musical scores. John Brosnan points out that the films are actually several miniature films (with beginnings, middles, and ends) strung together as set-pieces (Broccoli calls them "bumps") to create the overall whole. For instance, in

Dr. No

, we have the London sequence, the Kingston sequences (including the scenes with Miss Taro and Professor Dent), the Crab Key sequence, and the scenes in Dr. No's laboratory. The later films begin to lose the overall continuity between these set-pieces, and by

Moonraker

(1979), it is very difficult to follow the storyline, which gets lost in the shuffle. Perhaps the producers didn't care at this point whether the total movie made sense or not—it was the set-piece formula that had always worked before, and that is what they would continue to use.

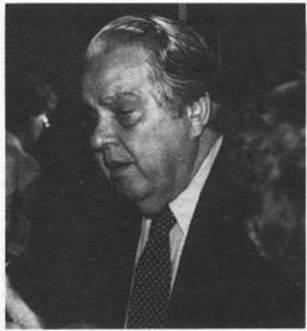

The Bond films producer Albert R. "Cubby" Broccoli, at a recent press conference in New York. Ever since co-producer Harry Saltzman left Eon Productions in 1974, Broccoli has held the reins of the films alone. (Photo by Richard Schenkman.)

THE SCREENPLAYS

T

he man responsible for most of the Bond screenplays is Richard Maibaum. Maibaum was born in New York, like Broccoli, in 1909. He began to study law, but became a writer for radio. His play

The Tree

was produced in New York in 1932, and he acted in several productions of the New York Shakespeare Repertory Theatre. His play

Sweet Mystery of Life

was produced on Broadway in 1935, after which he moved to Hollywood, where he wrote

They Gave Me a Gun

and

I Wanted Wings

for MGM. After World War II, he

worked for Paramount and wrote the screenplay for the 1949 film of

The Great Gatsby,

among others. In 1954, he wrote

Hell Below Zero

for producer Albert R. Broccoli.

When Broccoli first approached him about doing a Bond film, reportedly Maibaum felt that the Fleming novels were too violent and sexy to adapt to the screen. Even Fleming's biographer, John Pearson, agreed that the books were dead serious, and lacked humor. Sean Connery, who played James Bond in six of the films, has said that his wife at the time, Diane Cilento, read the first screenplay and advised Connery not to take the role unless some humor was added. Although the producers, along with director Terence Young, certainly deserve a share of the credit, Maibaum is probably the man most responsible for lacing the Bond screenplays with humor. Herein lies the major difference between the novels and the films—the latter are played for laughs. The humor in the early pictures was subtle and tongue-in-cheek; but it grew over the years to broad farce. John Brosnan calls

Moonraker

the "most expensive slapstick movie since

It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World

."