The Judgment of Paris (16 page)

Cabanel did have his supporters, a band of critics and connoisseurs soon dubbed

les Cabanellistes.

One of them writing under the name Claude Vignon (the pseudonym of a woman, Noemie Cadiot) compared the painting favorably with the works of Raphael and Correggio, arguing that Cabanel's Venus exemplified "ideal beauty embodied in a woman."

19

Others simply showed their unashamed appreciation of the work's blatant eroticism. The critic for the monthly

Revue des races latines

exulted that the painting portrayed "everything the imagination can dream of," while the expatriate Englishman Philip Hamerton drooled over the way the limbs of this "wildly voluptuous" goddess participated in "a kind of rhythmical, musical motion."

20

Cabanel also had another advocate. Emperor Napoléon III was a noted voluptuary who had enjoyed the attentions of numerous mistresses both before and after his marriage to Eugénie de Montijo ten years earlier. Among their ranks had been an Italian countess, Virginia di Castiglione, and Marianne de Walewska, the wife of his cousin, the Minister of State. His sexual appetite was said to be insatiable. Rumor had it that each evening a different woman was brought to the Palais des Tuileries, undressed in an anteroom, and escorted to the bed of His Imperial Majesty, who would exert himself until (in the words of one of these bedmates) "the wax on the ends of his mustache melts, causing them to droop."

21

Whatever the truth of these stories, in the spring of 1863 he was certainly enjoying a dalliance with a twenty-three-year-old former dressmaker and circus rider named Justine Leboeuf, who called herself Marguerite Bellanger, dressed in men's clothes and lived in the house in which he had installed her in the pleasant suburb of Passy.

If many art critics bewailed the sight of prostitutes on either the Rue Bréda or the walls of the Salon, the Emperor himself took, on both counts, a more progressive view. Prostitution during the Second Empire was not simply tolerated by his regime, it was also legalized.

22

Some 5,000 prostitutes had been registered at the Prefecture of Police in Paris in an attempt by the government to regulate and control the sex trade both in brothels—of which there were 190 operating legally—and on streets such as the Rue Bréda, where women were permitted to ply for business during certain prescribed hours. In addition to these registered prostitutes, Paris had as many as 120,000

files insoumises,

or "unruly women," unregistered streetwalkers who operated outside the official sanctions. This was a staggering statistic even in a city with a population in the early 1860s of 1.7 million, for it meant that more than thirteen percent of the entire population of Paris worked in prostitution.

Critics of the Emperor claimed that such rampant prostitution had less to do with either economic conditions or biological urges than with a government desire to quell dissent: prostitution, they argued, was a means of placating social unrest, functioning (like religion) as a kind of opiate of the people. One of the regime's fiercest critics, the socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, accused the Emperor of establishing a "pornocracy," with prostitutes operating as his "instruments of despotism."

23

Whether or not this was truly the case, one fact was certain: the Second Empire came into being thanks in part to the very direct help of one courtesan in particular, Lizzie Howard, the bootmaker's daughter who conquered London society, won Louis-Napoléon's heart and, in 1851, supported his regime by lending him 800,000 francs with which he was able to entertain (and to bribe) important members of the French military.

24

To the disgust of Proudhon and others, Miss Howard had been rewarded for this and other services with the title of Comtesse de Beauregard. By 1863 she had retired, at the age of forty, to a life of modest luxury at Versailles.

If the Emperor took a forbearing attitude toward prostitution, he was likewise unperturbed by nudity in art, his supposed treatment of Courbet's

Bathers

notwithstanding. Though he knew next to nothing about art, Cabanel's was, however, a name with which he could conjure. In 1861 he had purchased

Nymph Abducted by a Faun,

and two years later he again showed his appreciation for Cabanel's aphrodisiac style by buying

The Birth of Venus

for 15,000 francs (with some press reports excitedly putting the price as high as 40,000 francs). This evenhandedness was typical of Louis-Napoléon: having purchased one of the

Refusés,

the still life by Salingre, he promptly acquired the most conspicuous painting in the official Salon.

The Emperor's appreciation of Cabanel's work was no doubt rooted in its sensual qualities rather than any perceived reflections of "ideal beauty." Whatever his reasons, though, word of this acquisition, as well as the controversy over its supposed celebration of the pleasures of physicality, made the painting by far the most popular exhibit at the Salon of 1863 and Cabanel one of the most famous names in French art.

T

HE NUMEROUS DUTIES of the Marquis de Chennevières did not extend themselves, in 1863, to making arrangements for the Salon des Refusés, which was to be held in an annex of the Palais des Champs-Élysées. Nor was any money for organizing or publicizing this counter-exhibition forthcoming from the government. Chennevières and Nieuwerkerke, like most members of the Selection Committee, were desperate for this rival exhibition to fail: a popular and critical success would deal a heavy blow to their authority and prestige.

The task of advertising the show and printing a catalogue therefore fell to Antoine Chintreuil and his small group, who had three weeks to prepare everything. They placed notices in many newspapers, including

La Presse

and

Le Siècle,

both announcing the forthcoming Salon des Refusés and canvassing participating artists for information about themselves and their works. The catalogue was put together, a short preface stated, "with notes hastily collected from all over the place," and was rushed on the eve of the exhibition to a printer in the Rue des Grands-Augustins, a short distance from the Committee's headquarters in the studio of Jean Desbrosses.

1

Starved of government funds, the Committee had been fortunate to find a patron in the Marquis de Laqueuille, a wealthy aristocrat who was the proprietor of a journal called

Les Beaux-Arts.

2

Sympathetic to the plight of the rejected artists, Laqueuille edited the catalogue, found the printer for it, and met all the bills out of his own pocket. Miraculously, copies were ready when the Salon des Refusés opened its doors on May 15. However, unlike those for the official Salon, catalogues for the Salon des Refusés could not be sold inside the Palais des Champs-Élysées—yet one more obstruction placed in the way of the rejected artists. Laqueuille therefore provided one more service, arranging for hawkers to sell the catalogue in the street outside the exhibition.

The Catalogue of Works of Painting, Sculpture, Engraving, Lithography and Architecture Refused by the Jury of 1863 and Exhibited, by the Decision of His Majesty the Emperor, in the Salon Annex in the Palais des Champs-Élysées

ran to eighty pages. It listed 781 works of art by 366 painters, 64 sculptors, and a handful of architects and engravers. However, more works than these would actually go on show in this "annex" to the regular Salon. Chintreuil and his friends admitted in their preface that the catalogue "could not be made as complete as the committee wished" due to difficulties in contacting a number of the exhibiting artists. For example, one of the painters they had trouble tracking down was a virtually unknown thirty-three-year-old landscapist named Camille Pissarro; his surname was misspelled "Pissaro" and his forename left blank. Another exhibitor unknown to the committee—indeed, unknown to almost everyone in Paris—was a young friend of Pissarro named Paul Cézanne; he received no mention at all in the catalogue.

The catalogue of

Refusés

was incomplete for another reason as well. Of the more than 2,000 artists rejected from the Salon, fewer than 500 elected to show their work in the Salon des Refusés. In their catalogue, Chintreuil and his committee expressed their "major regret" about the many artists who had withdrawn work—including almost 2,000 paintings—from the show. Their unwillingness to participate, wrote Chintreuil, deprived both the public and the critics of seeing a truly representative sample of the sort of work that had inspired this unparalleled counter-exhibition in the first place.

One artist who had not voluntarily withdrawn his painting, but who nonetheless failed to appear among the other Refusés, was Gustave Courbet. This most infamous artist enjoyed the unique distinction in 1863 of having been rejected from both the regular Salon and the Salon des Refusés. Then age forty-four, he had been the maverick of French art for more than a dozen years, constantly embroiling himself in controversy and acrimony. Throughout his turbulent life he seems faithfully to have followed advice given to him at a tender age by his grandfather: "Shout loud and march straight ahead."

3

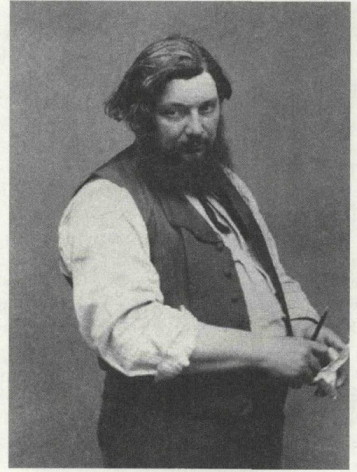

Courbet, like both Manet and Meissonier, had taken a career path that eschewed the École des Beaux-Arts in favor of independent study and periods of heedless bohemianism. The son of a prosperous vintner and landowner near Ornans, in farming country near the French—Swiss border, he had entered the seminary in Ornans at the age of twelve but divulged such monstrously precocious sins in the confessional that none of the priests would grant him absolution. His career in the priesthood thus nipped in the bud, he moved to Paris some years later to study law, though most of his time was spent sketching Old Masters in the Louvre or warming the benches of various beerhouses. Largely self-taught as a painter, he did not enjoy early acclaim: all but three of the twenty-four paintings he sent to the Salons between 1841 and 1847 were refused, largely at the insistence of François Picot. Typically, his first Salon painting, in 1844, was a self-portrait. Few painters had ever done as many portraits of themselves as the narcissistic Courbet, who remained his own favorite subject even as, by the 1860s, his fondness for beer and cider meant that the dark-haired, high-cheekboned good looks of his youth had given way to ruddy-faced corpulence.

Success had finally come Courbet's way at the Salon of 1849 with

After Dinner at Ornans,

an atmospheric interior scene that won him a handful of good reviews, a Salon medal, and a feast in his honor in his hometown. But the barbed comment of one reviewer—"No one could drag art into the gutter with greater technical virtuosity"

4

—typified the reluctant admiration that many people felt for the talented but undisciplined Courbet, who, in works such as

A Burial at Ornans, The Stonehreakers

and

The Bathers,

used vast canvases to depict, not gods and heroes, but ordinary farmers, peasants and prostitutes. So notorious had his canvases become by the middle of the 1850s, not just in France but in Europe as a whole, that a prominent notice in a casino in Frankfurt stated that "Monsieur Courbet's pictures must not be discussed in this club."

5

Gustave Courbet (Nadar)

Yet by the early 1860s Courbet finally seemed to have watered down his beer. He had enjoyed a highly successful Salon in 1861 with uncontroversial and widely acclaimed scenes of hunters, stags and foxes. Enthusiastic words of praise came from Théophile Gautier, while an admiring Chennevières—who had hitherto shown scant regard for the beer-swilling socialist—tried unsuccessfully to purchase one of the works,

Fighting Stags,

for the State. A Legion of Honor was even mooted, a decoration that Courbet, the maturing rebel, secretly craved. However, this accolade never materialized, leaving Courbet to believe, rightly or wrongly, that the Emperor had personally vetoed it. In true Courbet fashion, he decided to exact a pitiless revenge.

Courbet had spent the latter half of 1862 and the first few months of 1863 in Saintes, north of Bordeaux, on an estate called Rochemont that belonged to a young art collector and republican named Étienne Baudry. His absence from Paris meant that he missed the excitement over both the petition to Walewski and the announcement of the Salon des Refusés. Still, he made the most of his days at Rochemont, conducting an affair with the wife of a draper and astounding the locals with his capacity for drink. On one memorable occasion he was said to have downed, before dinner, six bottles of wine and a bowl of coffee half-filled with cognac.

6

He managed to produce a number of paintings, mainly of flowers, though he also began work on a canvas of quite a different sort.

Return from the Conference,

which depicted seven drunken priests staggering back home from an assembly, was deliberately intended to shock and offend. After sending the provocative work to the Salon jury in April, Courbet had relishingly predicted to a friend that, if this work were selected, "there will be an uproar. I expect that so audacious a painting has never been seen."

7