The Judgment of Paris (59 page)

Meissonier toured the ruins with a friend, the architect Hector Lefuel. A favorite of Napoléon III, the sixty-one-year-old Lefuel had built, among other things, the new Baroque-style addition to the Louvre that opened in 1857—and that would have become one more scorched tourist attraction had not rains fallen on May 26, extinguishing the fires that had consumed the Louvre's library. As the two men walked past the fire-gutted Tuileries, Meissonier's attention was caught by an arresting sight. Facing eastward, looking through the rubble of the Tuileries toward the Louvre, he could see, framed in the wreckage, the bronze sculptural group on top of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel. This sixty-three-foot-high triumphal arch had been built at the same time as the Vendôme Column and, like the column, was intended to commemorate Napoléon's military victories. Originally it had been crowned with the four bronze horses looted by Napoléon from the Basilica of San Marco in Venice, but after the horses were returned to Venice in 1815 the sculptor François-Joseph Bosio was commissioned to make a replacement—the triumphal chariot that Meissonier could glimpse through the burned-out wreckage. Below this chariot, in the remains of the Tuileries, he could see a poignant but inspiring sight in the Salle des Maréchaux, the grand room that one of the Empress Eugénie's ladies-in-waiting had called "the finest in the palace."

4

It had been the venue for the balls held each winter in the Tuileries during the Second Empire, and included among its lavish decorations were a series of shields bearing the names of Napoléon's victories. Two of these had survived the incineration that destroyed much of the rest of the palace. "I was suddenly struck," wrote Meissonier, "by the sight of the words, Marengo and Austerlitz, the names of two incontestable victories, which appeared, shining and intact. In an instant, I saw my picture."

5

Meissonier promptly installed himself in a nearby sentry box and went to work on a watercolor sketch of this symbolically charged scene. On a piece of paper sixteen inches wide he painted the piles of rubble, the precarious walls, the distant chariot and, at the very top, the two shields commemorating resplendent French victories. This

plein-air

work took a week, during which he also found time to indulge his passion for doodling on walls, sketching the figure of a horseman onto the side of the sentry box. A passing souvenir-hunter then helped himself to a genuine Meissonier, since the graffito "was cut out by someone," he later complained, "and taken I know not where." The sentry box had also served another purpose, that of protecting the painter from falling debris. He returned to the site one morning to have the watchman tell him: "Ah, Monsieur Meissonier! You had a narrow escape. You had scarcely left the place yesterday when this stone fell down, just where you had been standing." The stone, Meissonier observed, was "a huge fragment of the cornice, which would certainly have killed me."

6

Returning to his studio in Poissy, Meissonier turned his watercolor sketch into an oil painting entitled

The Ruins of the Tuileries.

At the bottom of the work he painted a foundation stone on which he inscribed the words GLORIA MAJORUM PER FLAMMAS USQUE SUPERSTES ("The glory of our forefathers survives the flames"). The meaning of the work was abundantly clear.

7

It was not, like

Remembrance of Civil War,

a frank record of the bloody horrors of civil strife, displaying broken barricades and heaps of bodies. Meissonier wished to show, instead, that the glories of French history were undimmed and the potency of its symbols and monuments unsullied by these same sort of bloody horrors—and by events such as the felling of the Vendôme Column and the torching of the Tuileries and the Hôtel de Ville. The spirit of Napoléon, and of the French people, had survived Bloody Week, a survival epitomized by the words "Marengo" and "Austerlitz" emblazoned across the ruins and the triumphal chariot rising above them. This might have been wishful thinking in the dark aftermath of the Commune; but the vision, together with a passionate hatred of Gustave Courbet, was one that would guide and console Meissonier in the months to come.

Édouard Manet returned to Paris at the end of May or beginning of June, after some fifteen weeks away from the capital.

8

He arrived with Suzanne, Léon and his mother by train from Tours, in the Loire Valley, following a leisurely progress up the Atlantic coast that included stops in La Rochelle, Nantes and Saint-Nazaire. He had clearly been dallying along the coast, reluctant to return to Paris while the Communards were still in power. "I'm not looking forward to the return to Paris at all," he had written to Bracquemond from Arcachon a few days after the events of March 18.

9

Upon his return, he was profoundly distressed by everything he saw. "What terrible events," he wrote to Berthe Morisot, who had left Paris for Cherbourg. "Will we ever recover from them? Everyone blames his neighbor, but the fact is that we're all responsible for what has happened."

10

Manet discovered that his studio in the Rue Guyot had been badly damaged during Bloody Week, though all his canvases, both in Théodore Duret's cellar and in the apartment in the Rue de Saint-Petersbourg, remained intact. He immediately transported all of them to a new studio next door to his mother's apartment and, in the weeks that followed, began work on a lithograph entitled

Civil War

and a watercolor called

The Barricade.

According to legend, these two works were based on scenes he had personally witnessed after his return to Paris.

Civil War

depicted, in a scene reminiscent of Meissonier's

Remembrance of Civil War,

an overrun barricade beneath which a kepi-wearing National Guardsman lay dead, while

The Barricade

featured a firing squad blasting away at several captured Communards. Duret claimed this first work was based on a corpse Manet had seen sprawled at the corner of the Rue de 1'Arcade and the Boulevard Malesherbes. "He made an on-the-spot sketch of it," declared Duret.

11

However, Duret was in America at the time and so could hardly have known firsthand what Manet did or did not see or sketch. His claim is highly dubious unless one can believe the corpse somehow arranged itself, through an astonishing coincidence, into exactly the pose Manet had used for his

Dead Toreador,

the figure excised seven years earlier from

Incident in a Bull Ring.

Rather than being an "authentic" piece of artistic reportage, Manet's

Civil War

was an obvious reworking of this earlier scene. Exactly the same can be said of

The Barricade,

an even more blatant revamping of

The Execution of Maximilian.

Manet clearly used artistic license rather than eyewitness observation or on-the-spot sketches in order to depict the horrors of Bloody Week and condemn political violence.

12

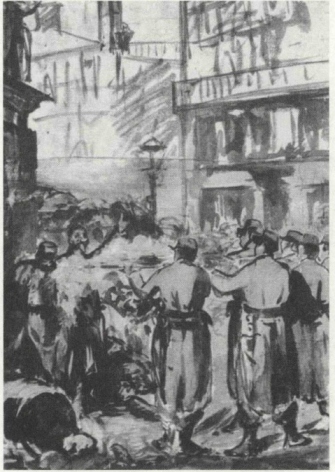

The Barricade

(Édouard Manet)

These were disillusioning days for Manet. Émile Zola, who had returned to Paris to find his apartment blessedly intact, wrote at this time to Cézanne: "Paris is being reborn. As I have often told you, our reign has begun!"

13

But Manet could feel no such optimism. Even before the Commune he had complained to Bracquemond that there were "no disinterested people around, no great citizens, no true republicans, only party hacks and ambitious types."

14

The civil strife brought on by the Commune and its brutal suppression made him even more angry and depressed about the state of French politics. His hatred of Adolphe Thiers—"a demented old man"

15

—was unbounded. The only politician in whom he put any store was Léon Gambetta, the lawyer and populist orator who had heroically organized the resistance against the Prussians following his white-knuckle balloon ride out of Paris. After resigning in March over the terms of the peace treaty negotiated by Thiers and then spending the weeks of the Commune in Spain, Gambetta returned to the National Assembly in a July by-election.

Manet took to riding the train with Gambetta each morning to Versailles, where the National Assembly was still sitting. The two men had known one another for a number of years, since Gambetta, a thirty-three-year-old bachelor and dedicated bohemian, was no less than Manet an enthusiastic habitué of café society. In 1871 he was a radical revolutionary in the process of mellowing into a moderate and articulate spokesman for social equality. He was opposed to what he called "intriguers, adventurers, dictators, ruffians"—that is, the class of swashbuckling bankers, aristocrats and Bonapartists that, in his opinion, had ruled France for the years of the Second Empire. But he was equally against what he called "something even more grave, the unforeseen explosion of the inflamed masses, who suddenly obey their blind fury."

16

Gambetta's moderate political opinions, with their suspicion of both the radical left and the authoritarian right, no doubt reflected Manet's own convictions at this time. Manet made sketches of him on the train, trying to persuade him to sit for a portrait; but Gambetta politely declined the offer. Notoriously ugly and unkempt, he was known as "Cyclops" after his right eye, injured in an accident in 1849, was surgically removed in 1867 and replaced with a glass one. He may have felt that a portrait of him executed by Manet would almost have been guaranteed to draw gibes from the critics and gleeful squirts of ink from the caricaturists.

When not traveling with Gambetta to Versailles, Manet spent the summer of 1871 wandering aimlessly from one café to another. Gradually friends such as Degas and Éva Gonzales had returned to Paris, though Berthe Morisot, whose health suffered badly during the siege, remained in Cherbourg. Manet continued to see her mother, who found his behavior and opinions "insane" but, following a soirée at the Manet home, was able to report the good news to Berthe that "Mademoiselle Gonzales has grown ugly."

17

By August, Manet's doctor diagnosed a nervous depression and urged him to leave Paris for the seaside. He seems to have required little urging and promptly departed with Suzanne and Léon for Boulogne-sur-Mer, where he spent the month of September. He did little work apart from a number of pencil and watercolor sketches of crinoline-clad figures playing croquet. These studies were eventually worked into a canvas called

Croquet at Boulogne

showing three women and two men (one of them posed by Léon) in the midst of a match at the Établissement des Bains. Like his painting of Léon astride a

vilocipede,

the work captured an image of modern life, a genteel sport that had recently become popular following its introduction from across the English Channel. Croquet had been described by one exponent in England as, oddly enough, a healthy substitute for war but a moral danger zone because—and this was one of the main reasons for its popularity—it was played by men and women together.

18

But Manet's canvas suggests neither moral impropriety nor war continued by other means. A picture of a middle-class leisure activity, it was strikingly different in its subject matter from either

Civil War

or

The Barricade,

offering no hint of the horrors its author had undergone.

The Comte de Nieuwerkerke, the man who had ruled the French art world for almost two decades, had fled Paris in September 1870, disguised, humiliatingly, as a valet. By 1871 he was living in exile in England, on the seafront at Eastbourne. Yet Nieuwerkerke's replacement did not give Manet and the painters in the Café Guerbois any particular cause for cheer. Under the Third Republic the fine arts became the responsibility of what was called the Ministry of Public Instruction, Cults and Fine Arts; and in November 1870 Charles Blanc, the fifty-eight-year-old founder of the

Gazette des Beaux-Arts,

became Director of Fine Arts. Manet's father had known Blanc many years earlier, but this friendship was about the only thing that could possibly have recommended the two men to each other.

Though his brother was Louis, the "Red of the Reds," Charles Blanc was, if anything, even more conservative in his views than Nieuwerkerke. Chennevières described him, in a grand understatement, as "more a supporter of Ingres and the Académie des Beaux-Arts than of Courbet and the Commune."

19

In fact, Blanc had published a biography of Ingres, whom he idolized, a year earlier, and for several decades he had been the most prolific and articulate exponent of the sort of Neoclassicism celebrated at the École des Beaux-Arts. In his lofty conception of art, Eve was the original representative of ideal beauty, but by plucking the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge she had plunged the world into a catastrophic state, a sort of Platonic world of appearances in which the ideal was obscured by the humdrum and ugly material world. Blanc believed that the ability to see through the veil of appearances, and glimpse the ideal beyond, was "obscure, latent and sleeping" among the majority of men. However, great artists—by whom he meant especially Ingres and the painters of the Italian Renaissance—"carry within themselves this idea of the beautiful in a state of light."

20

The true mission of art was therefore to show the "idea of the beautiful" that concealed itself behind the flickering shadows of the fallen world. "Art is the interpretation of nature" was his motto,

21

by which he meant that art should not portray nature in all its warts but should idealize it instead. Not surprisingly, he was vehemently opposed to Realism and paintings of

la vie moderne,

believing that artists who imitated nature and everyday life were slaves to appearance.