The Killing Sea (14 page)

Authors: Richard Lewis

The plain gold

band in Sarah's palm glinted in the bright lights of the ship's morgue. Her mother's wedding ring, given to her by the chaplain. The search team, still scouring Tiger Island's jungle and the surrounding sea for her father, had recovered her mother's remains. She was now behind cold steel doors.

The chaplain hovered by Sarah's shoulder. Probably anticipating a flood of grief. The doctor on her other side no doubt had a tranquilizer at the ready.

She studied the ring. Felt nothing. She wished the doctor had a medicine to help her feel something. What was wrong with her? When she at last

turned away, her eyes dry as stone, the chaplain gave her a curious look but remained silent.

Peter was in the sick bay's intensive care. Recovering well, the doctors said. He was, too. During her last visit to see him, Peter had asked about Surf Cat. Off chasing mice, Sarah said.

It was great being back with people who understood her. Yet there was a sense in which they didn't understand at all, not the way Ruslan did.

Had he found his father yet? She was sure he had. She tried to envision their joyous reunion, but the scene kept slipping away from her.

The ship's media officer appeared in the doorway. “It's time to get ready,” he said to Sarah.

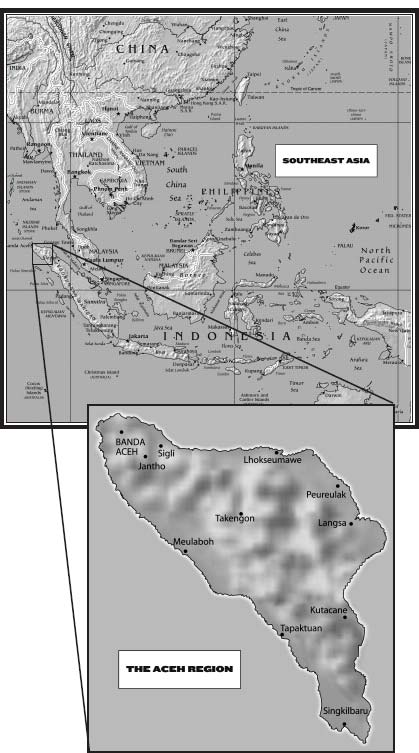

There'd been such intense international media interest in the Bedford Children's Tsunami Drama (as headlined in one major newspaper) that it was decidedâby whom, Sarah wasn't sureâto have a single press conference. Sarah would read a prepared account of her story, which the ship's media officer had helped her write. The press conference was going to be held on Meulaboh's military base, which also served as international relief headquarters.

The ship's captain had earlier ordered clothes for her and Peter from a big shopping mall in Medan, the closest city. Jeans and tops, and, as

she had embarrassedly whispered to one of his aides, underwear as well. For the press conference, though, she wanted to wear a long-sleeved dress, or at least a skirt and blouse.

“No problem,” the ship's media officer said, “if you don't mind wearing secondhand.”

In a nook of the enormous ship were several crates of donated clothes that had not yet made it to shore. Sarah found a decorous long-sleeved dress in a blue flower print with an embroidered white collar. Not at all her style, but it fit.

“I'd like a scarf to cover my head,” she said.

“I don't think there are any here,” the officer said. “These are all clothes, not accessories.”

“Can we get one somewhere?”

“You're not going to a mosque, just a press conference.”

“It's still their country. I'd like to wear one. A sign of respect.”

The media officer grumpily replied that he'd see what he could do.

Sarah arrived in the late afternoon at the military compound, wearing a plain blue scarf borrowed from one of the ship's female crew. The media officer escorted her. When she descended from the helicopter and saw the array of satellite dishes outside the building she was to speak in, and

the crowd of people within, her nerves nearly failed her. She'd always hated speaking in public. Now she was going to stand in front of the whole world.

Officials were standing by to receive her. An orange cat drowsed in the arms of one Indonesian officer, who stepped forward to Sarah with a smile. “Yours, I think?” he said.

“Surf Cat!” Sarah exclaimed with delight, taking the cat from the man's arms to kiss its furry head. She turned to Officer Hertzig, whom she now knew to be a major. “This is Peter's cat. He'll be real happy to see him. Is it possible for Surf Cat to get a ride out to the boat?”

Major Hertzig winked. “The ship. Yeah, I think it's possible. I'll take care of it. Come here, kitty.”

The media officer murmured in her ear, “Sarah, people are waiting.”

She gathered up her nerves and shook hands with the local military commander and several other dignitaries. A plump man in a blue UN vest and a bandaged elbow gave her a reproachful look, murmuring, “You really should have come with us.” She recognized him as one of the two men from the red helicopter.

The military commander ushered her into the building. At the front was a long table covered in green baize. In the center of the table, in front of a

metal folding chair, sprouted a miniature forest of microphones. The commander pulled out the chair for Sarah. The intense heat was as smothering as a blanket, but thankfully, the media officer aimed one of the floor fans on her. She was acutely aware of the battery of cameras trained on her, and the pack of journalists behind them, holding recorders and notebooks at the ready.

She read her speech. This was her story, but it felt as though she were reading about another girl.

As she read, she sensed something was not right. Aisyah. The mute girl. The story said nothing about them. To not mention them seemed wrong. She put down the sheets of paper. Looking directly at the cameras, she spoke of them, and of Ruslan, too, and the telling at last became her own story.

Yet a funny thingâthe journalists didn't seem to care about that. They wanted more of her. Just her and Peter. The media officer filtered their shouted questions, allowing Sarah to reply to individual ones.

Yes, her brother was doing fine, as she'd already said in her speech, and her relatives were at the moment flying out to Aceh.

No, her father hadn't been found yet, but the marines were still looking and she was certain he would soon be. No, that wasn't an irrational

hope, her father was strong, a survivor, and next question please?

Yes, the remains of her mother had been retrieved from Tiger Island. Yes, yes, yes, she had buried her mother on the beach, hadn't they listened to her speech?

How did she feel about burying her own mother? Well, God, she said, how do you think I felt? But she knew that her anger at the question was a clever sham.

Still the journalists weren't sated. They wanted to devour her with their questions. Sarah glanced out the window, wishing to be outside and alone, and saw several refugee children peering through the louvered panes. A resilient curiosity was back in their eyes.

Another, more genuine anger rose in her. “Why are you all so interested in me?” she said. “We just happened to be passing by. This isn't my tragedy, the Bedford family tragedy. This is an Aceh tragedy. See these kids out there? You should be telling the world their stories, not mine.”

She got up, refusing to answer any more questions.

From the back of the room came a familiar voice. “Sarah! Sarah!”

She paused, standing on her toes and squinting

over the crowd. Ruslan pushed forward, leading a man by the hand. She recognized the man at once. Ruslan's father, his smile full of dazed joy. “Thank you, Sarah,” he said. “Thank you, thank you.”

Sarah started to take his offered hand between both of hers in the polite local way, but then, on an impulse she couldn't stop any more than she could stop the tears blurring her vision, she flung her arms around him as cameras whirred and clicked.

Ruslan and Sarah

rode in the back of a military truck heading for Ujung Karang. He had asked for a lift because Sarah wanted to see his house, which by God's grace and strong construction had not been flattened by the tsunami. His father was at the mayor's office, registering Ruslan's name on the survivor's roll, and couldn't come.

Sarah kept toying with a gold ring on a chain hanging around her neck. “My mother's wedding ring,” she said. She bit her lip and released it. “The journalists asked what it was like to bury my own mother. What could I tell them? It was just hard work. I can't feel anything for her. Except, you know, this blank nothing. I know she didn't really

love me like she did Peter, but she was my mother. She did her best, I know. Why can't I feel? Am I a monster?”

Ruslan firmly shook his head. “No. Don't you think that.”

“It scares me, makes me wonder what kind of person I am.”

“You don't have to worry about that, Sarah. I know because I know you.”

She gave him a quick smile but said nothing.

The truck drove down the main boulevard, the only street that had been cleared, and stopped by the town's stadium. Ruslan helped Sarah down from the back of the truck and led her across dried mud to his house.

“I couldn't believe it when I first saw it,” he said. Even now, on his second visit, there was something shocking about the building's naked appearance, standing alone amidst the ruins of the neighborhood. “What's funny is I ran and ran from the tsunami and nearly drowned anyway, but if I'd just climbed to the roof, I would have been okay.”

“But you didn't know.”

“No, I didn't.” He looked out over the distant point. A half-dozen people picked through the remains of their homes. “So many people didn't know anything.”

“Can I look inside?”

“Sure. But everything's ruined.”

“Who cares, when you have your father back?”

He didn't have to reply. The house was nothing, less than nothing, not even in the same universe, compared to that.

“I'm so happy for you, Ruslan.”

He heard the truth of that in her voice, and saw it too, her happiness rising in her wide smile and in her blue eyes, and this when she still had her own father missing.

“You'll find him,” he said. “They might have found him already. You sure you don't want to go back to the boat?”

“No.” She took his hand, her long fingers curling around his, the warmth of her soft palm spreading all through him. She held his hand for three heartbeats, four, and then squeezed and let go. “I want to have a look inside.”

A foot of drying black mud covered the floor of the front parlor, and the walls and ceiling were badly discolored. A strong mildew odor rose from the damp sofa. Magazines and books lay scattered about, their pages pasted together. The only undamaged item, on the coffee table, was the notebook from the helicopter, opened to the drawing of his father.

She glanced at it and blurted, “But what if my dad's dead?”

How he wished he could give her some of his own father to reassure her. “Don't give up hope, Sarah.”

“It's getting to be like this washing machine. Hope, dread, hope, dread. It's about all I can feel.”

“That's how I felt too.”

She gave him a smile. “You're right. Don't give up hope. Ever. Hey, where's your room?”

“Upstairs.”

She climbed the stairs ahead of him. The doors to the three rooms on the second floor were closed. At the top landing she said, “You stay here. I want to guess which room is yours.” She walked down the short hall and stopped in front of the third door. “This is your room. Has the best light for drawing and painting.”

He grinned. “That's right.”

She opened the door.

He belatedly realized something and rushed to intercept her, but he was too late. She'd spotted his drawing of her, still taped to the wall, tinted brown by the water, but the smudged blue of her eyes and pink of her lips still visible. She stood before it, her head tilted a little as she studied it.

He wanted to vanish. “Um, that was when you first stopped in Meulaboh, when your boat engine was broken. I'd never drawn a Westerner.”

“It's reallyâ¦do I really look like that?”

Disappointment shot through his embarrassment. “You don't like it?”

“No, no, I like it a lot, but you've made me, I don't know, more mysterious than I am.”

“You were mysterious. I didn't know you.”

“You made me prettier, too.”

The artist in Ruslan said with sure confidence, “That's you, just as you are.”

She nodded at the poster of Siti Nurhaliza. “Am I prettier than her?”

Ruslan was about to gallantly say yes, when he paused. His blood sloshed back and forth, and he knew that truth was far more important than flattery.

“No. But she's not you.”

Sarah turned to him. He was afraid she could hear his pounding heart. She slipped into his arms, pressed her head against his shoulder. “I don't think Peter and me would've made it if it hadn't been for you,” she said. “Thank you.”

“You're welcome.” What a silly thing to say. Couldn't she feel the way his heart was stampeding all over the place?

She drew away a little to look at him. “Anybody ever tell you that you have beautiful eyes?” she murmured.

He kissed her then. How could he not? It was as easy as falling.

When they finally broke apart, she rested her forehead against his. “You remember what my dad looked like?”

“His nose was a little

bengkok

, bended, to the right. This way.” Ruslan pressed a finger to his own nose.

She drew back and smiled. “Broke it in college. An amateur boxing match. He always said he'd get it fixed, but my mom said, don't you dare, I love your nose.” Her smile became a laugh. “He'd say, you love me for my nose? and she'd say, absolutely, I fell in love with your nose and I married your nose, and if you change it, I'm going to have to divorce it. You know, a lot of my friends' parents divorced, but I was lucky, I really was.” Her laughter died. “Do you think you can draw a picture of him? For good luck, like with your father.”

Instead of using the notebook downstairs, he picked up the sketch pad on his desk, the top page already dry from the sunlight, and began to draw.

Â

Sarah leaned against the windowsill, watching him. She'd be leaving him soon, she knew. They could make promises about staying in touch and all that, but life didn't work that way. Soon, all he'd be was a memory. She wanted to remember this moment for the rest of her life. How he looked. His mussed-up hair. The way the corner of his lips twisted in concentration. The focused look of those gorgeous eyes.

Â

Ruslan remembered to the last wrinkle the face of Sarah's father. But an artist draws the truth of what he sees. And now, after the tsunami, he was seeing more clearly than he had ever seen before. The truth that he needed to distill, for Sarah's sake, guided his hand.

It didn't take long. He had never created anything more true and certain in his life.

Â

Sarah took the sketch that he quietly handed to her.

“Thanks,” she said, and then lost all her words. The sketch wasn't of her father.

It was her mother.

And in the simple, graceful lines of her gently smiling face, in the eyes that looked right into her, Sarah saw all the love that her mother had always

had for her, and how absolutely, utterly wrong she'd been to have ever doubted it.

Something gave way within her, and the raw waters of grief came rushing in.