The Knave of Hearts

Read The Knave of Hearts Online

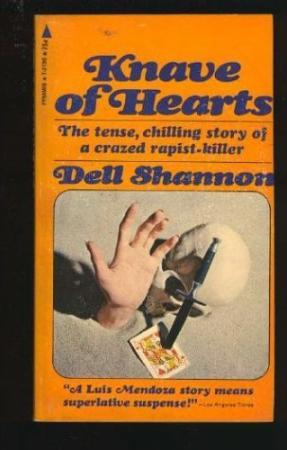

Authors: Dell Shannon

The Knave of Hearts

Dell Shannon

1982

ONE

"So that’s all, enough! The same old

story—¡

siempre la trampa

,

sure! I’ll be damned if—"

"Oh, damn you and whatever you want to think—the

trap, always the same susp— And what makes you think I’d have

you?

¡A ningun precio

,

thanks very much. Get out, go away, I can’t—"

"

¡Un millón de gracias,

le deseo lo propio

—-the same to you!"

He lost his temper about once in five years, Mendoza, and when he did

it wasn’t a business of loud violence; he had gone dead white and

his voice was soft and shaking, and his eyes and his voice were cold

as death and as hard. "You—"

"Get out for God’s sake-

¡largo

de aqui!

—you can go to hell for all I—"

And she didn’t lose her temper often either, but it didn’t take

her that way when she did; she was all but screaming at him now, taut

with rage, and if she’d had a weapon to hand she’d have killed

him.

"

¡Rapidamente

,

anywhere away from you!

¡Y para todo, muchas

gracias!

" That was sardonic, and pure

ice; he snatched up his hat and marched out, closing the door with no

slam, only a viciously soft little click.

Alison stood motionless there for a long moment, her

whole body still shaking with the anger, the impulse to violence; she

breathed deep, feeling her heart gradually slow its pounding. And

now, of course, she could think of all she should have said, longed

to say to him. This cheap cynical egotist, only the one thing in his

mind—every obscene word she knew in two tongues, she’d like

to—she should have—

And then, a while after that, she drew a long

shuddering breath and moved, to sit down in the nearest chair. The

fury was dead in her now, and that was another difference between

them; it never lasted long with her. She sat there quite still; her

head was aching slightly, then intolerably—aftermath of all that

primitive physical reaction. The little brown cat Sheba leaped up

beside her, asking attention, purring; Alison stroked her

mechanically. The kitten he had given her, the only thing she had

ever let him give her.

And wasn’t he a judge of women indeed, that way,

all ways! It was even a little funny: one of the first things he’d

said to her after they’d met—" A respectable woman like you,

she’s so busy convincing me she’s not after my money,

vaya

,

she’s never on guard against my charm."

Ought to take something for this headache.

She got up, went slowly through the bedroom to the

bathroom, swallowed some aspirin. In the garish overhead light there

she looked at herself in the glass impersonally. Alison Weir, and not

bad for thirty-one either; her best point, of course, was the thick

curling red hair, and the fine white skin and green-hazel eyes

complemented it. You might think Alison Weir could do pretty well for

herself, even with that foolish too-young marriage thirteen years in

her past, and no money now, to count. The women you saw—plain,

dowdy, careless, and bitchy too—selfish and mean women—who

somehow managed to find men for themselves . . .

"Oh, God," she whispered, and bent over,

clutching the slippery bowl against the pain. The aspirin hadn’t

taken hold yet, but this was a worse pain than the headache.

It was true, of course. She had forgotten now exactly

what thoughtless little phrase had started the ugly sudden

quarrel—his sarcastic answer and her quick, angry protest fanning

the flame. But in essence, his cynical suspicion was true, how true.

Setting the trap, to have him all hers.

She could not face the woman in the mirror, the pale

woman with the pain in her eyes. She went into the bedroom and sat

down on the bed. But from the beginning she had known him for what he

was. Not for any one woman: not ever, apart from his womanizing, all

of Luis Mendoza for any human person. He was just made that way. Like

one of his well-loved cats, at least half of him always secret to

himself, aloof. And maybe all because of the hurts he’d taken (for

she knew him very thoroughly, perhaps better than he suspected, and

she knew his terrible sensitivity). The hurts he’d taken as a dirty

little Mex kid running the slum streets—long before he came into

all that money. So that he’d never give anyone the chance to hurt

him again, ever, in any way. Never let anyone close enough to hurt

him. She had known: but knowing was no armor for the heart.

There was an old song her father used to sing: one of

the favorites, it was, around the cook-fires in the evening, in every

makeshift little construction camp she remembered—always one of the

locally hired laborers with a guitar. The easy desultory talk after

the day’s work, sporadic laughter, and the guitar talking too, as

accompaniment, in the blue southern night.

Ya

me voy . . . mi bien

, I must go, my love . .

.

te vengo a decir adios

—I

have come to tell you goodbye . . .

te mando

decir, mi bien, como se mancuernan dos

—to

tell you how disastrously two people can be yoked . . .

What use had it been to know? It was all her own

fault. Maybe she deserved whatever pain there would be, was—she had

known how it would end. Quarrel or no, he would have gone eventually.

When he’d had enough of her, when he’d found a new quarry—when

instinct told him she was coming too close, wanting too much of him.

And she did not need telling that all this while she alone hadn’t

held him—there’d been others, for variety.

Toma esa llavita de oro, mi bien

. . . take this gold key, open my breast and you’ll see how much I

love you . . .

y el mal page que me das

——and

how badly you repay me . . .

And the time had come, and he had gone; she would not

see him again; the interlude was over. It was for Alison Weir to pick

up the pieces the best way she could, and go on from here.

Toma

esa cajita de oro, mi bien

. . . take this

gold box, look to see what it contains . . .

lleva

amores, lleva celos—y un poco de sentimiento

—love

and jealousy, and a little regret . . .

Shameful, shameless, that she could not feel any

resentment, any righteous hatred, that—for what he was—he had

left her to this pain. No self-respect as half—armor against it:

despicable, that she could summon no shred of pride to keep anger

alive.

It was going to be very bad indeed, somehow finding

out how to go on—somewhere—without him. That was no one’s

fault, hers or his. No one deliberately created feelings; they just

came. No one could be rid of them deliberately, either.

It was going to be very bad. All the ways it could

be, not just the one way. Because there had been also (would it help,

this objective terminology for emotions?) a companionship: their

minds operating on the same wave length, as it were.

"But I should be ashamed," and she was

startled to hear her own voice. "I should be ashamed—"

not to hate. She put her hands to her face; she sat very still,

bracing herself against the pain.

"Post-mortems!" said Mendoza violently.

"Religion! ‘Saved from Satan and thus confessing my sins!’ "

He slapped Rose Foster’s signed statement down on his desk. "What

the hell are we supposed to do with this?"

"Don’t look at me,” said Hackett, "I

didn’t handle the Haines case, and neither did you—by the grace

of God. All for the best in this best of all worlds, isn’t it?—damn

shame Thompson had to drop dead of a heart attack at fifty, but at

least it’s saved him from some rough handling by the press. What’d

the Chief say?"

"You don’t need the answer to that one,"

said Mendoza. "

Tomemos del mal el

menos

—the lesser of two evils. Nothing

definite to the press—no statements for the time being. Get to work

on it and find out, find out everything, top to bottom! But no

washing dirty linen in public."

He lit a cigarette with an angry snap of his lighter

and swiveled round in his desk-chair to face out the window, over the

hazy panorama of the city spread below. He didn’t like this

business; nobody in the department who knew anything about it liked

it; but he might not be taking it so violently except for that damned

fight with Alison last night.

He smoked the cigarette in little quick angry drags,

nervous. Women! There was a saying.

Sin

mujeres y sin vientos, tendriamos menos tormentos

—without

women and without wind, we’d have less torment.

Absolutamente

,

he thought grimly. Scenes like that upset him; he liked it kept nice

and easy, the smooth exit when an exit was indicated and that was

that. Usually he managed it that way, but once in a while—women

being women—a scene was unavoidable. He might have known it would

be, with Alison: not the ordinary woman. He was sorry about it, that

it had ended that way. Apart from anything else, he had liked

Alison—as a person to be with, not just a woman—they’d

understood each other: minds that marched together. But women—!

Always wanting to go too deep, put it on the permanent basis. Sooner

or later the exit had to be made. He was only sorry, hellishly sorry,

that this one had had to be made that way.

But it was water under the bridge now, and the sooner

he stopped brooding on it the better.

God knew he had enough to occupy his mind besides.

Abruptly he swiveled back and met Hackett’s

speculative stare. Art Hackett knew him too damned well, probably

guessed something was on his mind besides this business .... Hackett

didn’t matter. Hackett nice and cozy in his little trap, not

knowing yet it was one: Hackett two weeks married to his Angel, still

the maudlin lover.

He picked up the Foster woman’s statement again and

looked at it with distaste. I know I done awful wrong and now I been

saved into the true religion I want to clear my conscience once for

all . . .

"If that," said Hackett, "is so, it’s

damned dirty linen, Luis. And it can’t be kept a secret forever.

There was the hell of a lot of publicity over Haines, not too long

ago. It’d be news with a capital N—and when it comes to that,

would it be such a hot idea to hide it up, for the honor of the force

so to speak?" He shrugged and shook his head.

"That," said Mendoza, "is just one

unfortunate aspect. As you say, at least Thompson’s dead and

whatever they say about him he won’t hear. Also, he makes a very

convenient scapegoat, doesn’t he, tucked away underground? We can

always give it out the poor fellow was failing—all very sad, but

such things will happen, obviously he was prematurely senile and

didn’t know what he was doing. Which is one damned lie. And what

the hell is this worth?" He flicked the statement

contemptuously. "Sure, a lot of publicity—before the trial,

after the trial. A lot of people sympathetic to Haines and his

family, believing in him. Here’s a damn-fool female turned

religious fanatic—who’s to say she didn’t make the whole thing

up, just to get her name in the papers?"

"She had his pipe," said Hackett. “The

wife’s identified it."

"All right—

¡vaya por

Dios!

—the wife was panting to identify it,"

said Mendoza irritably. "Did she really look at it so close?"

Hackett got out a cigarette and turned it round in

his fingers, looking at it. "You taking the stand we can’t be

wrong? It happens, Luis. Not often, but it happens."

"

No lo niego

,

I don’t deny it. It happens. If it happened here, sure, the press

boys’ll get hold of it, and you know what they’ll say, what the

outcome will be, as well as I do. Stupid blundering cops—prejudiced

evidence—and the muddleheaded editorials about the death penalty

and circumstantial evidence!

¡Es lo de

siempre

, the same old story—

¡por

Dios y Satanás!

" He laughed without

humor.

"And bringing it up again," agreed Hackett,

"every time somebody we get for homicide looks wide-eyed at a

press camera and says, ‘I swear I’m not guilty.' You needn’t

tell me. But there it is."