The Labyrinth of Osiris

THE LABYRINTH OF OSIRIS

www.transworldbooks.co.uk

Author by Paul Sussman

THE LOST ARMY OF CAMBYSES

THE LAST SECRET OF THE TEMPLE

THE HIDDEN OASIS

THE

LABYRINTH

OF OSIRIS

PAUL SUSSMAN

BANTAM PRESS

LONDON · TORONTO · SYDNEY · AUCKLAND · JOHANNESBURG

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

61–63 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

A Random House Group Company

First published in Great Britain

in 2012 by Bantam Press

an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Paul Sussman 2012

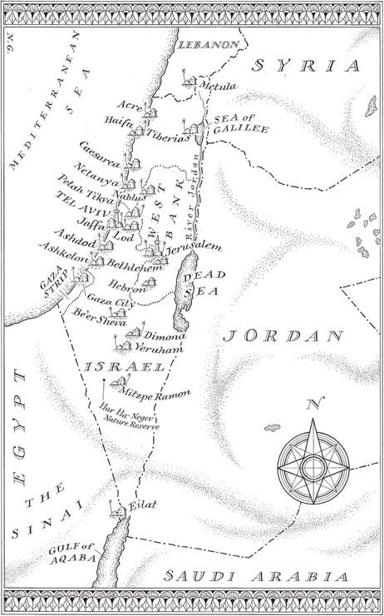

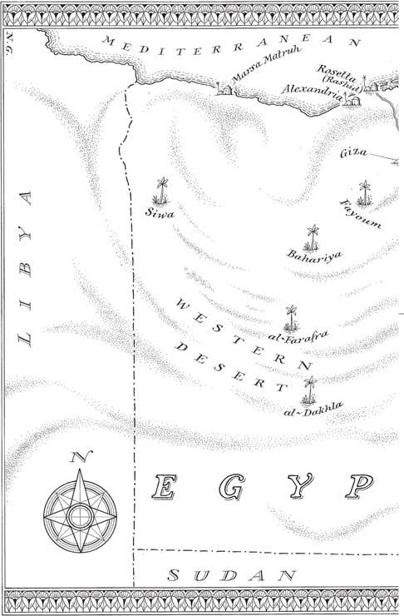

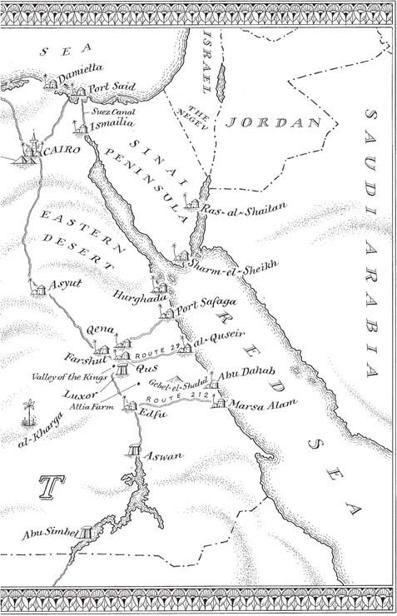

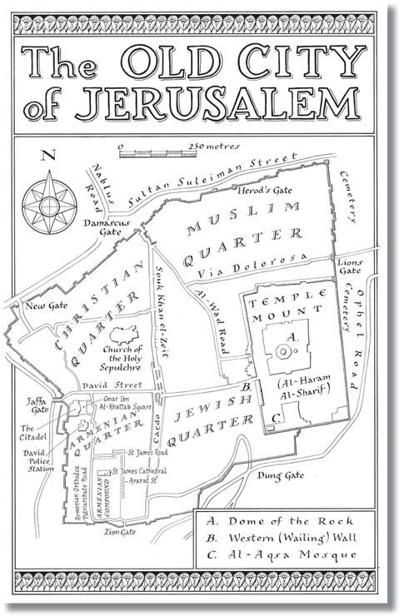

Maps © Neil Gower 2012

Paul Sussman has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-8021-9400-8

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Addresses for Random House Group Ltd companies outside the UK can be found at:

www.randomhouse.co.uk

The Random House Group Ltd Reg. No. 954009

The Random House Group Limited supports the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC®), the leading international forest-certification organization.

Our books carrying the FSC label are printed on FSC®-certified paper.

FSC is the only forest-certification scheme endorsed by the leading environmental organizations, including Greenpeace.

Our paper procurement policy can be found at

www.randomhouse.co.uk/environment

Typeset in 11/14pt Caslon 540 by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

For Team Sussman – Alicky, Ezra, Jude and Layla.

With love, always.

PROLOGUE

L

UXOR

, E

GYPT: THE WEST BANK OF THE

N

ILE

, 1931

Had the boy not decided to try a new fishing spot, he would never have heard the blind girl from the next village, nor seen the monster who attacked her.

Usually he fished a small inlet just beyond the giant reed banks, downriver of where the Nile ferry docked. Tonight, on a tip-off from his cousin Mehmet, who claimed to have seen shoals of giant

bulti

drifting in the shallows, the boy had gone upriver, past the outlying cane fields of Ba’irat, to a narrow sandbank screened from sight by a dense grove of

doum

palms. The place had a good feel to it, and he cast immediately. Barely had his hook hit the water when he heard the girl’s voice. Faint but audible. ‘

La, minfadlak!

’ No, please!

He lifted his head, listening, his line dragging in the pull of the current.

‘Please, don’t,’ came the voice again. ‘I’m scared.’

And then laughter. A man’s laughter.

Laying down his rod, he climbed the mud bank fronting the river and moved into the palm grove. The voice had come from the grove’s southern end and he angled in that direction, following a narrow dirt path, treading carefully so as not to make any noise or disturb the horned vipers that lurked in the undergrowth and whose bite was deadly.

‘No,’ came the voice again. ‘In God’s name, I beg you!’

More laughter. Cruel laughter. Teasing.

He stooped and picked up a rock, ready to defend himself if necessary, and continued forward, following the path as it curved through the centre of the grove and back towards the shoreline. He caught glimpses of the Nile to his left, slats of mercury shifting beyond the palm trunks, but of the girl and her attacker he could see nothing. Only when he reached the edge of the grove and the trees fell away did he finally get a clear view of the assault.

A broad track crossed in front of him, emerging from the cane fields to his right and running down to the river. A motorbike stood there. Beyond, clearly visible in the silvery moonlight, were two figures. One, by far the largest of the pair, was kneeling with his back to the boy. He wore Western dress – trousers, boots, a dust-caked leather coat, even though the night was warm – and was holding down a much smaller figure in a

djellaba suda

. She didn’t appear to be struggling, just lay as if frozen, her face hidden by her violator’s sizeable frame.

‘Please,’ she groaned. ‘Please don’t hurt me.’

The boy wanted to shout out, but was afraid. Instead he crept forward and squatted behind an oleander bush, the rock still clasped in his hand. He could see the girl properly now and recognized her. Iman el-Badri, the blind girl from Shaykh Abd al-Qurna. The one they all laughed at because rather than doing the things girls ought to do – washing and cleaning and cooking – she instead spent her days in the old temples, tapping around with her stick and touching the carved picture writing, which people said she could understand simply by feel. Iman the witch, they called her. Iman the stupid.

Now, staring through the oleander leaves as the man pawed at her, the boy regretted his teasing, even though all of them had done it, even her own brothers.

‘I’m scared,’ she repeated. ‘Please don’t hurt me.’

‘Not if you do as I say, my little one.’

They were the first words the man had spoken, or at least the first the boy had heard. His voice was gruff and guttural, his Arabic heavily accented. He laughed again, pulling off her headscarf and running a hand through her hair. She started sobbing.

Terrified as he was, the boy knew he had to do something. Sizing up the distance between himself and the figures in front of him, he pulled back his arm, ready to launch the rock at the rapist’s head.

Before he could do so, the man suddenly came to his feet and turned, moonlight bathing his face.

The boy gasped. It was the face of a ghoul. The eyes weren’t proper eyes, just small black holes; nothing where the nose should have been. There were no lips, just teeth, unnaturally large and white, like an animal’s maw. The skin was translucently pale, the cheeks sunken, as if recoiling in disgust from the grotesque image of which they formed a part.

The boy knew him now, for he had heard the rumours: a

hawaga

, a foreigner, who worked in the tombs and had only empty space where his face should have been. An evil spirit, people said, who prowled at night, and drank blood, and disappeared for weeks on end into the desert to commune with his fellow demons. The boy grimaced, fighting back the urge to scream.

‘Allah protect me,’ he murmured. ‘Dear Allah, keep him away.’

For a moment he feared he had been heard, for the monster came forward a step and stared directly at the bush, his head cocked as if listening. Seconds passed, agonizing seconds. Then, with a low rasping chuckle, like the sound of a dog panting, the man walked to the motorbike. His victim clambered to her feet, still sobbing, although quieter now.

When he reached the bike the man pulled a bottle from the pocket of his coat, uncorked it with his teeth and swigged. He burped and swigged again, then returned the bottle to one pocket while removing something from the other. The boy could just make out straps and buckles and assumed it was a rider’s cap. Rather than putting it on his head, the man gave the thing a shake and slap and lifted it to his face, bringing his hands around behind his head to thread the straps. It was a mask, a leather mask, covering his face from the forehead down to just above the chin, with holes for his eyes and mouth. Somehow it made him look even more grotesque than the deformities it was designed to cover, and the boy let out another low gasp of terror. Again the man stared in his direction, white eyes shifting behind the leather, peering out as though from inside a cave. Then, turning, he grasped the motorbike’s handlebars and placed his foot on the kick-start.

‘You tell no one about this,’ he called to the girl, again speaking in Arabic. ‘You understand? No one. It’s our secret.’

He stamped down and the engine roared into life. He tweaked the throttle lever a couple of times, revving, then leant over and fumbled in one of the pannier bags slung across the back of the bike. Producing what looked like a packet or a small book – the boy couldn’t be certain – he walked back to the girl, seized her

djellaba

and stuffed the object among the folds of black material. To the boy’s disgust he then curled a hand behind her head and brought her face forward, pressing it against his own. She turned this way and that, seeming to gasp in disgust at the feel of the leather against her skin, before the man broke away and returned to his motorbike. He kicked up the front and rear stands, pulled on a pair of goggles, swung a leg over the seat and, with a final cry of ‘Our little secret!’, engaged the gear lever and roared off up the track, disappearing in a cloud of dust.

So terrified was the boy that it was several minutes before he dared move. Only when the sound of the engine had faded completely and the night was once again silent did he come to his feet. The girl had by now picked up her headscarf and retied her hair, mumbling to herself, letting out strange keening sounds that the boy might have mistaken for laughter had he not seen what had just been done to her. He wanted to go over and tell her it was all right, that her ordeal was over, but sensed that it would only compound her shame to know that it had been witnessed. He stood where he was, therefore, watching as she felt in the grass for her stick and started tapping her way up the track away from the river. She went fifty metres, then suddenly stopped and turned, looking directly at him.

‘

Salaam

,’ she called, her free hand protectively clutching her

djellaba

. ‘Is someone there?’

He held his breath. She called again, her sightless eyes straining, then continued on her way. He let her go, waiting till she rounded a bend and was lost among the cane plants. Then, making his way back through the palm grove, he picked up the path that ran alongside the Nile and broke into a sprint, his fishing rod forgotten. He knew exactly what needed to be done.

With its 488cc single-cylinder engine and 3-speed Sturmey Archer gearbox, the Royal Enfield Model J could reach a top speed of over sixty miles an hour. On the tarmac highways of Europe the man had had it up to almost seventy. Here in Egypt, where even the best roads were little more than glorified tracks, he rarely took it much beyond thirty. Tonight was different. Special. The alcohol and the euphoria made him reckless, and he pushed the speedometer up to forty-five, roaring north through the cane and maize fields, the Nile lost away to his right, the towering wave of the Theban massif tracking him to the left. He took frequent swigs from his whisky bottle and sang to himself, tunelessly, always the same song.

‘It’s a long way to Tipperary,

It’s a long way to go.

It’s a long way to Tipperary,

To the sweetest girl I know!

Goodbye, Piccadilly,

Farewell, Leicester Square!

It’s a long, long way to Tipperary,

But my heart’s right

here

!’

Most of the west bank hamlets were deserted, ghost villages, their

fellaheen

inhabitants having long since gone to bed, their mud-brick dwellings as dark and silent as tombs. Only in Esba were there signs of life. There had been a

moulid

here earlier in the evening and a few late-night stragglers still lingered outside: a pair of old men sitting on a bench puffing

shisha

pipes; a group of children throwing stones at a camel; a sweet-seller trudging home with his empty cart. They looked up as the motorbike passed, eyeing its rider suspiciously. The sweet-seller shouted at him and one of the children held his index fingers up to his forehead in the sign of

al-shaitan

, the Devil. The man ignored them – he was used to such insults – and rode on, a pack of dogs chasing him out of the village.

‘Mangy curs!’ he cried, leaning round and snarling at them.

He came to a crossroads and turned left, heading west, directly towards the massif, its rearing bulk glowing a dull pewter colour in the moonlight. Tiny paths criss-crossed its face like white veins, some of them the same paths the ancient tomb-workers must have used to cross the hills over three millennia previously, on their way to the Wadi Biban al-Moluk, the Valley of the Kings. He had walked those paths many a time over the years, much to the bewilderment of the archaeologists and other Westerners out here, who couldn’t understand why he didn’t just take a donkey if he wanted to appreciate the views. Carter was the only one who really understood, and even he was starting to turn bourgeois. The adulation had gone to his head. He was assuming airs and graces. The stubbornness and the tempers the man could stand, but not the airs and graces. It was only a tomb, for God’s sake. Fools, all of them. He’d show them. He

had

shown them, although they didn’t know it yet.

He reached the Amenhotep Colossi and slowed, raising his bottle in mock toast, then sped up again, following the road as it swung north past the ruined mortuary temples ranged along the foot of the massif. Most were no more than shadowy jumbles of shattered blocks and mud-bricks, barely distinguishable from the surrounding landscape. Only those of Hatshepsut, Ramesses II and, further on, Seti I, retained any of their original grandeur, elderly courtesans still trading on memories of youthful beauty. And, of course, behind him, south, at Medinet Habu, the great temple of Ramesses III, his favourite in all of Egypt, where he had first glimpsed the blind girl and everything had changed.

I’ll make her my own

, he had thought at the time, spying on her from behind a pillar.

We’ll be together for ever

.

And now they would be. For ever. It was what had kept him going through all those lonely months underground, the memory of her face, the small perfumed handkerchief he had taken with him. My little jewel, he called her. More radiant than all the gold in Egypt. And more precious. And now she was his. Oh happy day!

The road here was good, its dirt surface flattened and compacted by all the traffic the Tutankhamun discovery had brought to the area, and he pushed the Enfield up to fifty miles per hour, dust billowing behind him. Only as he came to Dra Abu el-Naga at the northern end of the massif – a scattering of mud-brick houses and animal pens perched on the slopes above the road – did he slow and pull over. To his left a pale ribbon of track wound away into the hills towards the Valley of the Kings. Directly ahead, at the top of a low brow, sat a single-storey villa with shuttered windows and a domed roof. He lifted his goggles and gazed at it, then drove on, motoring up to the front of the building where he cut the engine, removed the goggles and propped the bike against a palm trunk. Slapping the dust from his coat and boots, he took another long swig from the whisky bottle and marched across to the entrance, weaving slightly from the effect of the alcohol.

‘Carter!’ he bellowed, hammering on the door. ‘Carter!’

No reply. He hammered again, then took a couple of steps back.

‘I found it, Carter! You hear me? I found it!’

The building was silent and dark, no light visible behind the closed shutters.