The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (14 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

We now need a mental dictionary that specifies which words belong to which part-of-speech categories (noun, verb, adjective, preposition, determiner):

N

boy, girl, dog, cat, ice cream, candy, hot dogs “Nouns may be drawn from the following list:

boy, girl,…

”

V

eats, likes, bites

“Verbs may be drawn from the following list:

eats, likes, bites

.”

A

happy, lucky, tall

“Adjectives may be drawn from the following list:

happy, lucky, tall

.”

det

a, the, one

“Determiners may be drawn from the following list:

a, the, one

.”

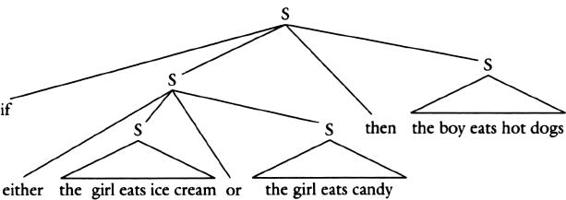

A set of rules like the ones I have listed—a “phrase structure grammar”—defines a sentence by linking the words to branches on an inverted tree:

The invisible superstructure holding the words in place is a powerful invention that eliminates the problems of word-chain devices. The key insight is that a tree is

modular

, like telephone jacks or garden hose couplers. A symbol like “NP” is like a connector or fitting of a certain shape. It allows one component (a phrase) to snap into any of several positions inside other components (larger phrases). Once a kind of phrase is defined by a rule and given its connector symbol, it never has to be defined again; the phrase can be plugged in anywhere there is a corresponding socket. For example, in the little grammar I have listed, the symbol “NP” is used both as the subject of a sentence (S NP VP) and as the object of a verb phrase (VP

NP VP) and as the object of a verb phrase (VP V NP). In a more realistic grammar, it would also be used as the object of a preposition (

V NP). In a more realistic grammar, it would also be used as the object of a preposition (

near the boy

), in a possessor phrase (

the boy’s bat

), as an indirect object (

give the boy a cookie

), and in several other positions. This plug-and-socket arrangement explains how people can use the same kind of phrase in many different positions in a sentence, including:

[The happy happy boy] eats ice cream.

I like [the happy happy boy].

I gave [the happy happy boy] a cookie.

[The happy happy boy]’s cat eats ice cream.

There is no need to learn that the adjective precedes the noun (rather than vice versa) for the subject, and then have to learn the same thing for the object, and again for the indirect object, and yet again for the possessor.

Note, too, that the promiscuous coupling of any phrase with any slot makes grammar autonomous from our common-sense expectations involving the meanings of the words. It thus explains why we can write and appreciate grammatical nonsense. Our little grammar defines all kinds of colorless green sentences, like

The happy happy candy likes the tall ice cream

, as well as conveying such newsworthy events as

The girl bites the dog

.

Most interestingly, the labeled branches of a phrase structure tree act as an overarching memory or plan for the whole sentence. This allows nested long-distance dependencies, like

if…then

and

either…or

, to be handled with ease. All you need is a rule defining a phrase that contains a copy of the very same kind of phrase, such as:

S

either S or S

“A sentence can consist of the word

either

, followed by a sentence, followed by the word

or

, followed by another sentence.”S

then S

“A sentence can consist of the word

if

, followed by a sentence, followed by the word

then

, followed by another sentence.”

These rules embed one instance of a symbol inside another instance of the same symbol (here, a sentence inside a sentence), a neat trick—logicians call it “recursion”—for generating an infinite number of structures. The pieces of the bigger sentence are held together, in order, as a set of branches growing out of a common node. That node holds together each

either

with its

or

, each

if

with its

then

, as in the following diagram (the triangles are abbreviations for lots of underbrush that would only entangle us if shown in full):