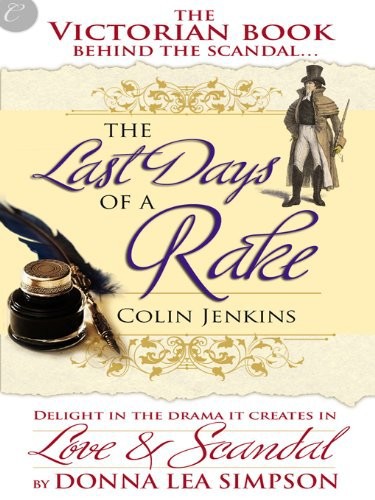

The Last Days of a Rake

Read The Last Days of a Rake Online

Authors: Donna Lea Simpson

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Historical, #90 Minutes (44-64 Pages), #Historical Fiction

In

Love & Scandal,

Collette Jardiniere is outraged when notorious roué Charles Jameson appears to take credit for

The Last Days of a Rake,

a novel she wrote under the pseudonym Colin Jenkins to satisfy Victorian convention.

Can a rake be true to himself, yet remain free from sin?

Edgar Lankin has lived the life of rake, a man who cares for nothing but the pleasures of the flesh. But it is the seduction—and abandonment—of a gentle maiden that turns him from mere gadabout to immoral cad. Too late, Lankin realizes his self-centered ways have left him incapable of finding enjoyment in anything. Now on his deathbed, he relates the shocking tale of his wasted life to John Hamilton, a school chum who chose a different path.

In telling his story, can Lankin find redemption for the trail of ruined lives he leaves behind?

Companion piece to

Love & Scandal

by Donna Lea Simpson

Dear Reader,

Thank you for purchasing this Carina Press launch title. During our journey these past months to acquire manuscripts, develop relationships with authors and build the Carina Press catalog, we’ve been working to fulfill the mission “Where no great story goes untold.”

If you’d asked me what I’d be doing a year ago, I never would have conceived I’d be working with the brilliant team behind Harlequin’s digital program to bring you a new and exciting digital-first imprint. I have long been a fan of Harlequin books, authors and staff and that’s why I’m so pleased to be sharing these first Carina Press launch titles with you.

At Carina Press, we’re committed to bringing readers great voices and great stories, and we hope you’ll find these books as compelling as we do. In this first month, you’ll find a broad range of genres that showcase our promise to Carina Press fans to publish a diversity of content. In the coming months, we’ll add additional genres and continue to bring you a wide range of stories we believe will keep you coming back for more.

We love to hear from readers, and you can e-mail us your thoughts, comments and questions to [email protected]. You can also interact with Carina Press staff and authors on our blog, Twitter stream and Facebook fan page.

Happy reading!

~Angela James

Executive Editor, Carina Press

www.carinapress.com

www.twitter.com/carinapress

www.facebook.com/carinapress

Donna Lea Simpson

Air, the true staff of life, was becoming more precious with each deeply drawn inhalation. How many breaths did he have left, and what would become of that last, sweet draught? Edgar Lankin lay on his bed by the window overlooking his beloved London. Dark clouds gathered, shadowing the city in a premature twilight, as coal smoke obscured the cityscape, blurring the shapes of chimneys and steeples.

This was his last view, but it mattered not that he could see little through the smudgy panes. His gaze was turned inward. He was caught, tangled in a web of remembrance. Tormented by a vivid panorama through his brain of all his past sins and the little he had been able to do to rectify them, once he understood what harm he had done in his adult years. Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust—when his soul took flight and his body was entombed, who would remember him with aught but anger and recrimination?

How odd, he thought, caught by the image, that after the final breath, the body was sent down, to be interred in the fond embrace of cool mud, while the soul—if one accepted the theology that he had shunned for most of his forty years—winged upward, lighter than air once released from its homely prison.

He sighed, rasped and coughed, the effort leaving him gasping for breath.

John Hamilton, his oldest friend, looked up from the book he was reading. “Lankin, old man,” he said, leaning toward him and holding a cup to Lankin’s lips. “How are you doing?”

After a cool drink of water, Lankin lay back, caught his breath and said, “I’m dying, John, and how are you?”

Hamilton sighed and shook his head, his eyes misting with friendship’s fond sorrow.

They had passed such a comment every evening for the last week, as John Hamilton faithfully visited, but this evening Lankin knew his time left on earth was measured in hours, or maybe even minutes, to be followed by an eternity of nothingness before the final resurrection. What had he done in his life that was worth this moment of kind regard and infinite regret? Who had he touched, what had he accomplished? Who, beyond John, would mourn his passing?

“Set aside your book, John, and let us talk,” he said, drawing upon reserves of strength that would dwindle quickly. “I fear this night and what it will bring.”

“I’m at your service, my good fellow,” Hamilton said, his gaunt, ascetic face gentle with compassion. “Of what do you wish to speak?”

The sun was descending, a brilliant ball of orange filtered muddily through the coal fire fog that drifted over the city. As silence fell between the two men, the last muted golden rays extinguished in the west, drowned by the distant ocean to rise for some other man’s morning. Lankin’s new philosophy, earned by the enforced thoughtfulness brought on by declining health, would not allow depression, but his spirits were declining from the knowledge that whatever he had been able to do to ameliorate the condition of those he had injured, his work was done now. It was his last sunset.

“Did I ever tell you about Susan?” Lankin murmured, turning away from the somber view and staring up at the ceiling.

“Susan? I don’t recall that name. Who is she?”

How simple it was to slip into the past for someone who had no future, Lankin reflected. Susan…fresh as a daisy, a glowing girl with skin like alabaster— No, that was too common a comparison for her. Her skin was like the petal of a dew-kissed, creamy rose. When Lankin touched her, it was to bruise that tender flower, to crush it with his insolent manhood.

But morose reflection did not do her justice. “Shall I tell you about Susan? I think of her often, but I fear the story does me poor credit. I need to unburden myself, and you—lucky fellow—shall be my father confessor. While you were studying your books and applying yourself to science and God, I—wretch that I was at one-and-twenty—was finding a way to corrupt the incorruptible.”

“That is a contradiction in terms I cannot allow,” Hamilton said with gentle humor, as he set his book aside, face down, on a table. “If something is incorruptible, then surely, by its very definition, it cannot be corrupted.”

“Still, I wonder what would have happened to Susan if I had not crossed her path that evening, at that long-ago ball, where she stood with her doughty chaperone.” Lankin stared at the ceiling, memorizing the pattern of shadows from the sickly city tree outside his window.

“If you had passed her by, she would have been ‘born again, not of corruptible seed, but of incorruptible’?” Hamilton quoted.

“I knew you would have a Biblical verse, my better friend.” Lankin paused to catch his breath and looked over at the other man. “Why do you stay, when I abused even you in my past miserable life?”

“A friend is tested not by smiles and handshakes, but by insults and rebuffs.”

“You are a well-tested friend.”

“Tell me the story, then, of Susan,” Hamilton said, as shadows deepened, creeping across the floor like a stealthy intruder on velvet shod feet. He got up and lit a taper from the smoldering fire, placing the candle on a small table between his chair and Lankin’s bed.

“Fill my water glass, and I will pretend it is wine one last time. Then I will speak of Susan, and some of those who came after. If you don’t mind, I will take on the conceit of speaking of myself in the third person, as a good storyteller must.”

“Be my Scheherazade, my good friend,” Hamilton said, his tone mild. The flickering candlelight shadowed his eyes, concealing the sorrow within them.

“If only by playing Scheherazade I could delay the inevitable, like that wondrous woman, but it may be that God is less merciful even than her king. I will not hesitate, and I will not spare myself in the telling. Prepare to hear that which will shock, dismay and disappoint you.”

When one is looking forward, the days of youth seem to stretch out along a shining path to forever. Once one is past them, though, the path behind contracts until, from the other end, it appears the merest garden walk, a few steps from the sheltering doorway of youth to the squalid dead-end street of fate. The beginning of a life journey is full of promise, and rarely is any destination forecast.

It was June of 1811; to Edgar Godolphin Lankin, just up from Oxford and wealthy due to the untimely death of an unlamented grandparent, the path ahead gleamed gold. Possessed of all the arrogance of youth, he was at the first step, as thoughtless and callow as any young man of wealth and moderate good looks could be. He had never absorbed the precious traits of humility and decency others he knew in school embodied. In fact, he made fun of such men, thinking himself above them.

So, in that glittering era, Lankin, with no need to form any intent beyond his own pleasure, set out to make his mark on London. Instead of the Godly or studious fellows like his worthy friend John Hamilton, who combined a religious nature with a scientific mind, he took as his pattern the Regent, that promulgator of all that was worldly, beautiful, artistic and licentious. That brilliant fellow was showing just how much he cared for his poor mad pater by holding a revelry at Carlton House—that brilliant palace of dreams—the like of which the world had never seen. All around the city festivities like the Carlton House debauch were in full gaudy bloom. Lankin, as a wealthy and indolent man about town with impeccable connections, had been invited to a few.

Now, before progressing further, it is important to know that in the dream that was his life, Lankin was the center, the beau ideal, the prize beyond price. To his thinking he united a unique sensibility, an appreciation for beauty, an understanding of humankind that was rare and precious, fitting him to be a man of the world, an epicure and a sybarite. If he had been a lesser man this attitude would have been ludicrous, but he was just wealthy, just discriminating and just handsome enough to justify such conceit. He attracted flatterers, sycophants, that tribe whose members will stay for champagne and sweetmeats, but abandon ship when it begins to founder and sink. Their horde is verminous, like so many flea-bit rats.

But who can blame them? It has ever been so in society. Money, after all, will buff away perceived faults into the appearance of glass. He was handsome, women said—too often in front of him—for again, wealth will often buy good looks. He was intelligent, though not wise, and witty, though not kind. He emulated Beau and Byron, and had his ticket for White’s on St. James, after rejecting invitations to join Boodle’s and the Alfred.

The night he met Susan he was as drunk as a young man should be after two bottles of claret and one of hock. But his mind was clearing, since he had cast up his accounts in the ornamental bushes on his way into Lady Phoenicia’s gala event in honor of the new Regent at her Mayfair home.

The air that night was crisp and light, fully as intoxicating as wine, and Lankin, in the company of another frivolous—if poorer—young man, was of a mind for mischief. Old cats and society dragons frowned in disapproval as Lankin and his friend lounged into the festivity, leering at exposed bosoms and surreptitiously patting bottoms in the most insolent manner. The fashion of the day for ladies was such that leering and patting, though uninvited, was rewarding. But after a half hour spent in such pleasantries, both were becoming bored.

“Lankin, let us get out of this place,” Felix Bellwether said, finally, after they had shocked their quota of old people.

Lankin was ready to go, for there were yet ancient watchmen to box and carriage horses to torment. But as fate would have it, he saw, that moment, descending the steps to the ballroom, a luminous goddess. She was as fresh as the spring air—a veritable Persephone—with golden hair piled high and decked with a coronet of pearls.

“Who is that?” he breathed, not expecting an answer. The young lady stood at the top of the stairs. She was gowned in palest green trimmed in gold, demure eyes downcast, while her companion was a formidable dame dressed in purple, her head topped by a plumed turban.

“Her?” Felix asked. “That’s Susan Bailey, a friend of m’sister’s.”

Thunderstruck, Lankin stared as she passed by him. He was instantly transported back to the springtimes of his childhood, when all the world was gold and green, fresh, new, with limitless possibilities. “Introduce me, there’s a good chappie,” he said to Felix, clapping him on the shoulder.

As the orchestra tuned their instruments, Bellwether led Lankin toward the bank of chaperone chairs, where Susan was just taking a seat with her society guardian.

“Hallo, Susie,” Bellwether said, lounging indolently on the back of one gilt-adorned chair. “This here is Edgar Lankin,” he said, hooking one thumb over his shoulder toward his friend, “just down from Oxford.”

The young woman smiled, but before she could speak, the elderly purple-gowned woman rose from her seat with some difficulty. “Young man,” she said, peering at Bellwether through her lorgnette, one eye monstrously larger than the other because of it, “some may allow such slack introductions, but I expect young gentlemen to behave correctly.”

“It’s all right, Lady Stoddart,” Susan Bailey said, her tone as light and sweet as a matins bell. “Felix and his sister are my childhood friends. Surely any friend of his would be suitable as an acquaintance?”

From such a promising beginning, how could the evening do aught but progress? Lankin stayed at the ball and danced the supper dance with Susan. Felix, bored by the proceedings, went off to the card room to lose what little money he had at whist.

She was so profoundly lovely, budding womanhood clothing her more beautifully than any costly raiment. Lankin and Susan’s tale might have been like a hundred, or a thousand, others. Mayhap they would have courted, and then, after a suitable interval (an innocent kiss, the fervid pressing of one hand over another) he would have sunk to one knee and begged for her lily-white hand in marriage. There were no impediments to tear them asunder, no sneering evil uncle trying to sell her to the highest bidder, no dark family secrets, no ill health in their immediate future. He was wealthy and well-born, she the same, with the added enticements of a good dowry, youth and a pristine reputation. Marriage and children would have followed. Then, given his character, the next sequence would surely have been infidelity, disenchantment, separation, and finally death. Just so would the skein of their lives have raveled if Lankin had been like others of his time and place, willing to follow the rules of life as set down by society and the church.

Such stories, the accounts of romances between suitably boring young people, are edifying for the public in the reassurance that a life governed by God and country will end in the preservation of society, if not in happiness for the individuals. But the devil was in Lankin; nay, not one devil but a legion of imps, the demons of pride, mischief, lust and conceit. He began, that very evening, to weave a veil of mystery over Susan, in a game of seduction that the innocent girl could not understand. He helped her evade her chaperone and took her for a stroll after dinner in the garden of the London house, awaiting the fireworks that had been promised as a part of the hideous Regency celebrations.

The night air was sweet, honeyed by the perfume of attraction and the sublime enchantment of youthful allure. She shivered, and he, chivalrous in his attempt to attach her, pulled off his jacket and gently drew it around her shoulders.

“Better?” he asked.

She nodded and looked up at him with shining eyes as blue as a summer sky. “You are very kind,” she murmured.

“And you are very lovely,” he countered, watching as she blushed. The urge to kiss her became a thrum of eagerness in his veins, like blood coursing in a rapid pulse. But as he attempted to draw her into the shadows, she pulled away.

“Mr. Lankin, you know we cannot disappear into the dark like that,” she said.

No sweet talk would convince her, for she was well raised and morally sound. They talked, after that, and watched the fireworks, but her reserve was the impetus for wretched desire in his breast. He, like countless men of his position and wealth, had experienced a woman’s charms many times from his youth to his manhood. Oxford, that vaunted center of learning and academia, was also a town of bar maids, chambermaids, the whole legion of “maids” who serve the lusts of men as well as their need for clean linens and ale. Lankin had had his share of maidservants and barmaids in his time, “knowing” them in the biblical sense.

So it was not for want of carnal satisfaction that his diabolical plan arose; any random pair of lips, breasts and legs would have slaked such lust. But Susan Bailey’s demure withdrawal left him curious. It was a challenge, doubly urged by his attraction to her and his pique at her sweet, sensible morality.

When they parted that evening, it was with food for innocent dreams on her part, and, for him, the knowledge in his breast that he was going to attempt the unfathomable. He was attracted to her both for her beauty and some element of youthful promise within her. But he felt himself above the common trap of falling in love, whatever that much-bandied word meant, and he certainly was not about to marry at such a young age. Therefore, what was left to do with the young lady?

Only one thing, to his mind; he began, that evening, to plot Miss Susan Bailey’s downfall, her complete surrender to him and, thus, her ruination. How could a man of previous spotty but not completely shocking reputation plan such a thing? Had he no perturbations of the spirit, no misgivings, given her innocence and the complete lack of her having done anything to invite such ruin?

Lankin was one of those pitiable souls void of conscience when it came to lives other than his own. He was invited to proceed by the sheer audacity of the scheme. It was a tricky thing to do—given how guarded young ladies were in those times and still are—but it was possible. Edgar Lankin was determined, and Miss Bailey was oblivious.

One month later, he had made little progress toward achieving his goal beyond a bet set up among new friends at his club. He had bragged so openly of his plan (only among those he knew receptive, of course, not among the older, more staid members of the society, and not naming the object of his intentions) that one gambling fellow had bet him he would not succeed. And so the betting book was laid open, and the bet, couched in suitably obscure phrases, was confirmed. But now it looked like he may have boasted too precipitously.

His fellow clubmen, who did not know the young woman in question beyond her initials,

S. B.,

had begun to taunt him with his failure. Fetes, balls, breakfasts and dinners were the only places he had been able to see Miss Bailey. Lankin recognized he was being led, by Susan and her chaperone, down a path that had forked from the one he had intended to firmly tread. Ahead, gleaming in the distance at the end of the path, was a church and Susan, guarded by the dragon, at a flower-decked altar.

The vision horrified him. He needed to either scuttle away from the beautiful girl, or make his final assault on the fortress of her virtue.

But in life, so much is chance. He was undecided which path he would take—defection or seduction—because despite his despicable intentions, he liked Susan Bailey. She was sweet and gentle, but not vacuous, nor thoughtless. There was little else to do most times in company for a young man and lady but talk, and she was well-informed, intelligent, with a bright vivacity that was pleasing to the most discriminating taste. If he had been a different kind of man, he said to himself often in his late night turmoil, she would make an ideal wife.

Chance made his decision, or at least, he was willing to blame chance.

When a bet is placed it has a time limit on its accomplishment, and one afternoon, as Lankin sprawled in a comfortable chair in the dark, smoky card room of his club, the bet holder, one George Sanders, approached him.

“I say, Lankin, you ready to call it quits and pay out on the S.B. bet? I could use my winnings about now.”

“What? I beg your pardon. What are you babbling on about, Sanders?” Lankin asked, peering up through a wreath of cigar smoke.

The man leaned over and lowered his voice, slanting his gaze to both sides, as he said, “That bet, ‘bout the beauteous little filly you are set to debauch. The mysterious S.B., who is not such a mystery, by the way, my good fellow. Time’s ‘bout up! You lose. I want m’money.” He held out his hand and waggled his fingers.

Lankin did not like Sanders’s tone, and the word “lose” held an unexpected sting. One such as he, with youth, wealth, looks and intelligence, could not lose to one such as Sanders, an aging, debauched, dim-witted, bulbous-nosed impecunious drunken gambler. He stood, towering over the other man. “Bring the betting book!” he commanded.

When it was brought, he pointed one finger at the date. He had seven days to accomplish the deed before forfeiting.

“But you said yourself the gel had gone off to her country haunt,” Sanders brayed.

That was true. But the ace up Lankin’s sleeve had yet to be played. “But I have an invitation, old man,” he drawled, laying the card out on the table in the form of a written invitation. “I am going to accept, and follow my sweet girl down to the country.”

Some of the others, those who had bet on Lankin’s success, applauded. “Make us proud!” one crowed.

“I will,” Lankin said.