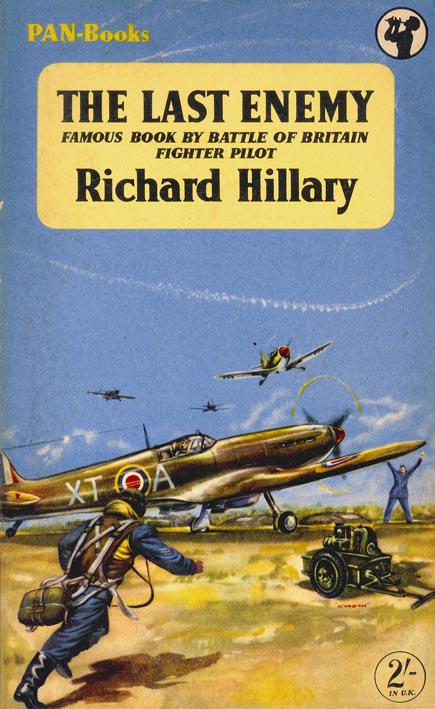

The Last Enemy Richard Hillary

Title: The Last Enemy Author: Richard Hillary eBook No.: 0501181.txt Edition: 1 Language: English Character set encoding: Latin-1(ISO-8859-1)—8 bit Date first posted: December 2005 Date most recently updated: December 2005

***** A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook *****

Produced: by Peter O’Connell

Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition.

Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file.

This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html

To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

Title: The Last Enemy Author: Richard Hillary

‘The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death’ I Corinthians xv. 26

For D.M.W.

PROEM

SEPTEMBER 3 dawned dark and overcast, with a slight breeze ruffling the waters of the Estuary. Hornchurch aerodrome, twelve miles east of London, wore its usual morning pallor of yellow fog, lending an added air of grimness to the dimly silhouetted Spitfires around the boundary. From time to time a balloon would poke its head grotesquely through the mist as though looking for possible victims before falling back like some tired monster.

We came out on to the tarmac at about eight o’clock. During the night our machines had been moved from the Dispersal Point over to the hangars. All the machine tools, oil, and general equipment had been left on the far side of the aerodrome. I was worried. We had been bombed a short time before, and my plane had been fitted out with a new cockpit hood. This hood unfortunately would not slide open along its groove; and with a depleted ground staff and no tools, I began to fear it never would. Unless it did open, I shouldn’t be able to bale out in a hurry if I had to. Miraculously, ‘Uncle George’ Denholm, our Squadron Leader, produced three men with a heavy file and lubricating oil, and the corporal fitter and I set upon the hood in a fury of haste. We took it turn by turn, filing and oiling, oiling and filing, until at last the hood began to move. But agonizingly slowly: by ten o’clock, when the mist had cleared and the sun was blazing out of a clear sky, the hood was still sticking firmly half-way along the groove; at ten-fifteen, what I had feared for the last hour happened. Down the loud-speaker came the emotionless voice of the controller: ‘603 Squadron take off and patrol base; you will receive further orders in the air: 603 Squadron take off as quickly as you can, please.’ As I pressed the starter and the engine roared into life, the corporal stepped back and crossed his fingers significantly. I felt the usual sick feeling in the pit of the stomach, as though I were about to row a race, and then I was too busy getting into position to feel anything.

Uncle George and the leading section took off in a cloud of dust; Brian Carbury looked across and put up his thumbs. I nodded and opened up, to take off for the last time from Hornchurch. I was flying No. 3 in Brian’s section, with Stapme Stapleton on the right: the third section consisted of only two machines, so that our Squadron strength was eight. We headed south—east, climbing all out on a steady course. At about 12,000 feet we came up through the clouds: I looked down and saw them spread out below me like layers of whipped cream. The sun was brilliant and made it difficult to see even the next plane when turning. I was peering anxiously ahead, for the controller had given us warning of at least fifty enemy fighters approaching very high. When we did first sight them, nobody shouted, as I think we all saw them at the same moment. They must have been 500 to 1000 feet above us and coming straight on like a swarm of locusts. I remember cursing and going automatically into line astern: the next moment we were in among them and it was each man for himself. As soon as they saw us they spread out and dived, and the next ten minutes was a blur of twisting machines and tracer bullets. One Messerschmitt went down in a sheet of flame on my right, and a Spitfire hurtled past in a half-roll; I was weaving and turning in a desperate attempt to gain height, with the machine practically hanging on the airscrew. Then, just below me and to my left, I saw what I had been praying for—a Messerschmitt climbing and away from the sun. I closed in to 200 yards, and from slightly to one side gave him a two-second burst: fabric ripped off the wing and black smoke poured from the engine, but he did not go down. Like a fool, I did not break away, but put in another three-second burst. Red flames shot upwards and he spiralled out of sight. At that moment, I felt a terrific explosion which knocked the control stick from my hand, and the whole machine quivered like a stricken animal. In a second, the cockpit was a mass of flames: instinctively, I reached up to open the hood. It would not move. I tore off my straps and managed to force it back; but this took time, and when I dropped back into the seat and reached for the stick in an effort to turn the plane on its back, the heat was so intense that I could feel myself going. I remember a second of sharp agony, remember thinking ‘So this is it!’ and putting both hands to my eyes. Then I passed out.

When I regained consciousness I was free of the machine and falling rapidly. I pulled the rip-cord of my parachute and checked my descent with a jerk. Looking down, I saw that my left trouser leg was burnt off, that I was going to fall into the sea, and that the English coast was deplorably far away. About twenty feet above the water, I attempted to undo my parachute, failed, and flopped into the sea with it billowing round me. I was told later that the machine went into a spin at about 25,000 feet and that at 10,000 feet I fell out—unconscious. This may well have been so, for I discovered later a large cut on the top of my head, presumably collected while bumping round inside.

The water was not unwarm and I was pleasantly surprised to find that my life-jacket kept me afloat. I looked at my watch: it was not there. Then, for the first time, I noticed how burnt my hands were: down to the wrist, the skin was dead white and hung in shreds: I felt faintly sick from the smell of burnt flesh. By closing one eye I could see my lips, jutting out like motor tires. The side of my parachute harness was cutting into me particularly painfully, so that I guessed my right hip was burnt. I made a further attempt to undo the harness, but owing to the pain of my hands, soon desisted. Instead, I lay back and reviewed my position: I was a long way from land; my hands were burnt, and so, judging from the pain of the sun, was my face; it was unlikely that anyone on shore had seen me come down and even more unlikely that a ship would come by; I could float for possibly four hours in my Mae West. I began to feel that I had perhaps been premature in considering myself lucky to have escaped from the machine. After about half an hour my teeth started chattering, and to quiet them I kept up a regular tuneless chant, varying it from time to time with calls for help. There can be few more futile pastimes than yelling for help alone in the North Sea, with a solitary seagull for company, yet it gave me a certain melancholy satisfaction, for I had once written a short story in which the hero (falling from a liner) had done just this. It was rejected.

The water now seemed much colder and I noticed with surprise that the sun had gone in though my face was still burning. I looked down at my hands, and not seeing them, realized that I had gone blind. So I was going to die. It came to me like that—I was going to die, and I was not afraid. This realization came as a surprise. The manner of my approaching death appalled and horrified me, but the actual vision of death left me unafraid: I felt only a profound curiosity and a sense of satisfaction that within a few minutes or a few hours I was to learn the great answer. I decided that it should be in a few minutes. I had no qualms about hastening my end and, reaching up, I managed to unscrew the valve of my Mae West. The air escaped in a rush and my head went under water. It is said by people who have all but died in the sea that drowning is a pleasant death. I did not find it so. I swallowed a large quantity of water before my head came up again, but derived little satisfaction from it. I tried again, to find that I could not get my face under. I was so enmeshed in my parachute that I could not move. For the next ten minutes, I tore my hands to ribbons on the spring-release catch. It was stuck fast. I lay back exhausted, and then I started to laugh. By this time I was probably not entirely normal and I doubt if my laughter was wholly sane, but there was something irresistibly comical in my grand gesture of suicide being so simply thwarted.

Goethe once wrote that no one, unless he had led the full life and realized himself completely, had the right to take his own life. Providence seemed determined that I should not incur the great man’s displeasure.

It is often said that a dying man re-lives his whole life in one rapid kaleidoscope. I merely thought gloomily of the Squadron returning, of my mother at home, and of the few people who would miss me. Outside my family, I could count them on the fingers of one hand. What did gratify me enormously was to find that I indulged in no frantic abasements or prayers to the Almighty. It is an old jibe of God-fearing people that the irreligious always change their tune when about to die: I was pleased to think that I was proving them wrong. Because I seemed to be in for an indeterminate period of waiting, I began to feel a terrible loneliness and sought for some means to take my mind off my plight. I took it for granted that I must soon become delirious, and I attempted to hasten the process: I encouraged my mind to wander vaguely and aimlessly, with the result that I did experience a certain peace. But when I forced myself to think of something concrete, I found that I was still only too lucid. I went on shuttling between the two with varying success until I was picked up. I remember as in a dream hearing somebody shout: it seemed so far away and quite unconnected with me…

Then willing arms were dragging me over the side; my parachute was taken off (and with such ease!); a brandy flask was pushed between my swollen lips; a voice said, ‘O.K., Joe, it’s one of ours and still kicking’; and I was safe. I was neither relieved nor angry: I was past caring.

It was to the Margate lifeboat that I owed my rescue. Watchers on the coast had seen me come down, and for three hours they had been searching for me. Owing to wrong directions, they were just giving up and turning back for land when ironically enough one of them saw my parachute. They were then fifteen miles east of Margate.

While in the water I had been numb and had felt very little pain. Now that I began to thaw out, the agony was such that I could have cried out. The good fellows made me as comfortable as possible, put up some sort of awning to keep the sun from my face, and phoned through for a doctor. It seemed to me to take an eternity to reach shore. I was put into an ambulance and driven rapidly to hospital. Through all this I was quite conscious, though unable to see. At the hospital they cut off my uniform, I gave the requisite information to a nurse about my next of kin, and then, to my infinite relief, felt a hypodermic syringe pushed into my arm.

I can’t help feeling that a good epitaph for me at that moment would have been four lines of Verlaine:

Quoique sans patrie et sans roi, Et tr?s brave ne l’?tant guere, J’ai voulu mourir a la guerre. La mort n’a pas voulu de moi.

The foundations of an experience of which this crash was, if not the climax, at least the turning point were laid in Oxford before the war.

BOOK ONE

1

Under the Munich Umbrella

OXFORD has been called many names, from ‘the city of beautiful nonsense’ to ‘an organized waste of time,’ and it is characteristic of the place that the harsher names have usually been the inventions of the University’s own undergraduates. I had been there two years and was not yet twenty-one when the war broke out. No one could say that we were, in my years, strictly ‘politically minded.’ At the same time it would be false to suggest that the University was blissfully unaware of impending disaster. True, one could enter anybody’s rooms and within two minutes be engaged in a heated discussion over orthodox versus Fairbairn rowing, or whether Ezra Pound or T. S. Eliot was the daddy of contemporary poetry, while an impassioned harangue on liberty would be received in embarrassed silence. Nevertheless, politics filled a large space. That humorous tradition of Oxford verbosity, the Union, held a political debate every week; Conservative, Labour, and even Liberal clubs flourished; and the British Union of Fascists had managed to raise a back room and twenty-four members.

But it was not to the political societies and meetings that one could look for a representative view of the pre-war undergraduate. Perhaps as good a cross-section of opinion and sentiment as any at Oxford was to be found in Trinity, the college where I spent those two years rowing a great deal, flying a little—I was a member of the University Air Squadron—and reading somewhat. We were a small college of less than two hundred, but a successful one. We had the president of the Rugby Club, the secretary of the Boat Club, numerous golf, hockey, and running Blues and the best cricketer in the University. We also numbered among us the president of the Dramatic Society, the editor of the Isis (the University magazine), and a small but select band of scholars. The sentiment of the college was undoubtedly governed by the more athletic undergraduates, and we radiated an atmosphere of alert Philistinism. Apart from the scholars, we had come up from the so-called better public schools, from Eton, Shrewsbury, Wellington, and Winchester, and while not the richest representatives of the University, we were most of us comfortably enough off. Trinity was, in fact, a typical incubator of the English ruling classes before the war. Most of those with Blues were intelligent enough to get second-class honours in whatever subject they were ‘reading,’ and could thus ensure themselves entry into some branch of the Civil or Colonial Service, unless they happened to be reading Law, in which case they were sure to have sufficient private means to go through the lean years of a beginner’s career at the Bar or in politics. We were held together by a common taste in friends, sport, literature, and idle amusement, by a deep-rooted distrust of all organized emotion and standardized patriotism, and by a somewhat selfconscious satisfaction in our ability to succeed without apparent effort. I went up for my first term, determined, without over-exertion, to row myself into the Government of the Sudan, that country of blacks ruled by Blues in which my father had spent so many years. To our scholars (except the Etonians) we scarcely spoke; not, I think, from plain snobbishness, but because we found we did not speak the same language. Through force of circumstance they had to work hard; they had neither the time nor the money to cultivate the dilettante browsing which we affected. As a result they tended to be martial in their enthusiasms, whether pacifistic or patriotic. They were earnest, technically knowing, and conversationally uninteresting.

Not that conversationally Trinity had any great claim to distinction. To speak brilliantly was not to be accepted at once as indispensable; indeed it might prove a handicap, giving rise to suspicions of artiness. It would be tolerated as an idiosyncrasy because of one’s prowess at golf, cricket, or some other college sport that proved one’s all-rightness. For while one might be clever, on no account must one be unconventional or disturbing—above all disturbing. The scholars’ conversation might well have been disturbing. Their very presence gave one the uneasy suspicion that in even so small a community as this while one half thought the world was their oyster, the other half knew it was not and never could be. Our attitude will doubtless strike the reader as reprehensible and snobbish, but I believe it to have been basically a suspicion of anything radical—any change, and not a matter of class distinction. For a man from any walk of life, were he athletic rather than aesthetic, was accepted by the college at once, if he was a decent sort of fellow. Snobbish or not, our attitude was essentially English.

Let us say, therefore, that it was an unconscious appreciation of the simple things of life, an instinctive distrust of any form of adopted aestheticism as insincere.

We had in Trinity several clubs and societies of which, typically, the Dining Club was the most exclusive and the Debating Society the most puerile. Outside the college, the clubs to which we belonged were mostly of a sporting nature, for though some of us in our first year had joined political societies, our enthusiasm soon waned. As for the Union, though we were at first impressed by its great past, and prepared to be amused and possibly instructed by its discussions, we were soon convinced of its fatuity, which exceeded that of the average school debating society.

It was often said that the President of Trinity would accept no one as a Commoner in his college who was not a landowner. This was an exaggeration, but one which the dons were not unwilling to foster. Noel Agazarian, an Armenian friend of mine in another college, once told me that he had been proposed for Trinity, but that the President had written back to his head master regretting that the College could not accept Mr. Agazarian, and pointing out that in 1911, when the last coloured gentleman had been at Trinity, it had really proved most unfortunate.

We were cliquy, extremely limited in our horizon, quite conscious of the fact, and in no way dissatisfied about it. We knew that war was imminent. There was nothing we could do about it. We were depressed by a sense of its inevitability but we were not patriotic. While lacking any political training, we were convinced that we had been needlessly led into the present world crisis, not by unscrupulous rogues, but worse, by the bungling of a crowd of incompetent old fools. We hoped merely that when war came it might be fought with a maximum of individuality and a minimum of discipline.

Though still outwardly complacent and successful, there was a very definite undercurrent of dissatisfaction and frustration amongst nearly everyone I knew during my last year.

Frank Waldron had rowed No. 6 in the Oxford Crew. He stood six-foot-three and had an impressive mass of snow-white hair. Frank was not unintelligent and he was popular. In my first year he had been president of the Junior Common Room. The girls pursued him but he affected to prefer drink. In point of fact he was unsure of himself and was searching for someone to put on a pedestal. He had great personality and an undeveloped character. Apart from myself, he was the laziest though most stylish oarsman in the University, but he was just that much better to get away with it. He did a minimum of work, knowing that it was essential to get a second if he wished to enter the Civil Service, but always finding some plausible argument to convince himself that the various distractions of life were necessities.

I mention Frank here, because, though a caricature, he was in a way representative of a large number of similarly situated young men. He had many unconscious imitators who, because they had not the same prowess or personality, showed up as the drifting shadows that they were.

The seed of self-destruction among the more intellectual members of the University was even more evident. Despising the middle-class society to which they owed their education and position, they attacked it, not with vigour but with an adolescent petulance. They were encouraged in this by their literary idols, by their unquestioning allegiance to Auden, Isherwood, Spender, and Day Lewis. With them they affected a dilettante political leaning to the left. Thus, while refining to be confined by the limited outlook of their own class, they were regarded with suspicion by the practical exponents of labour as bourgeois, idealistic, pink in their politics and pale-grey in their effectiveness. They balanced precariously and with irritability between a despised world they had come out of and a despising world they couldn’t get into. The result, in both their behaviour and their writing, was an inevitable concentration on self, a turning-in on themselves, a breaking-down and not a building-up. To build demanded enthusiasm, and that one could not tolerate. Of this leaning was a friend of mine in another college by the name of David Rutter. He was different not so much in that he was sincere as in that he was a pacifist.

‘Modern patriotism,’ he would say, ‘is a false emotion. In the Middle Ages they had the right idea. All that a man cared about was his family and his own home on the village green. It was immaterial to him who was ruling the country and what political opinions held sway. Wars were no concern of his.’ His favourite quotation was the remark of Joan’s father in Schiller’s drama on the Maid of Orleans, ‘Lasst uns still gehorchend harren wem uns Gott zum K?ng gibt,’ which he would translate for me as, ‘Let us trust obediently in the king God sends us.’

‘Then,’ he would go on, ‘came the industrial revolution. People had to move to the cities. They ceased to live on the land. Meanwhile our country, by being slightly more unscrupulous than anyone else, was obtaining colonies all over the world. Later came the popular press, and we have been exhorted ever since to love not only our own country, but vast tracts of land and people in the Empire whom we have never seen and never wish to see.’

I would then ask him to explain the emotion one always feels when, after a long time abroad, the South Coast express steams into Victoria Station. ‘False, quite false,’ he would say; ‘you’re a sentimentalist.’ I was inclined to agree with him. ‘Furthermore,’ he would say, ‘when this war comes, which, thanks to the benighted muddling of our Government, come it must, whose war is it going to be? You can’t tell me that it will be the same war for the unemployed labourer as for the Duke of Westminster. What are the people to gain from it? Nothing!’

But though his arguments against patriotism were intellectual, his pacifism was emotional. He had a completely sincere hatred of violence and killing, and the spectacle of army chaplains wearing field boots under the surplice revolted him.

At this time I was stroking one of the trial crews for the Oxford boat just previous to being thrown out for ‘lack of enthusiasm and cooperation.’ I was also on the editorial staff of the University magazine. David Rutter once asked me how I could reconcile heartiness with aestheticism in my nature. ‘You’re like a man who hires two taxis and runs between,’ he said. ‘What are you going to do when the war comes?’

I told him that as I was already in the University Air Squadron I should of course join the Air Force. ‘In the first place,’ I said, ‘I shall get paid and have good food. Secondly, I have none of your sentiments about killing, much as I admire them. In a fighter plane, I believe, we have found a way to return to war as it ought to be, war which is individual combat between two people, in which one either kills or is killed. It’s exciting, it’s individual, and it’s disinterested. I shan’t be sitting behind a long-range gun working out how to kill people sixty miles away. I shan’t get maimed: either I shall get killed or I shall get a few pleasant putty medals and enjoy being stared at in a night club. Your unfortunate convictions, worthy as they are, will get you at best a few white feathers, and at worst locked up.’

‘Thank God,’ said David, ‘that I at least have the courage of my convictions.’

I said nothing, but secretly I admired him. I was by now in a difficult position. I no longer wished to go to the Sudan; I wished to write; but to stop rowing and take to hard work when so near a Blue seemed absurd. Now in France or Germany one may announce at an early age that one intends to write, and one’s family reconciles itself to the idea, if not with enthusiasm at least with encouragement. Not so in England. To impress writing as a career on one’s parents one must be specific. I was. I announced my intention of becoming a journalist. My family was sceptical, my mother maintaining that I could never bring myself to live on thirty shillings a week, which seemed to her my probable salary for many years to come, while my father seemed to feel that I was in need of a healthier occupation. But my mind was made up. I could not see myself as an empire-builder and I managed to become sports editor of the University magazine. I dared not let myself consider the years out of my life, first at school, and now at the University, which had been sweated away upon the river, earnestly peering one way and going the other. Unfortunately, rowing was the only accomplishment in which I could get credit for being slightly better than average. I was in a dilemma, but I need not have worried. My state of mind was not conducive to good oarsmanship and I was removed from the crew. This at once irritated me and I made efforts to get back, succeeding only in wasting an equal amount of time and energy in the second crew for a lesser amount of glory.

Mentally, too, I felt restricted. It was not intellectual snobbery, but I felt the need sometimes to eat, drink, and think something else than rowing. I had a number of intelligent and witty friends; but a permanent oarsman’s residence at either Putney or Henley gave me small opportunity to enjoy their company. Further, the more my training helped my mechanical perfection as an oarsman, the more it deadened my mind to an appreciation of anything but red meat and a comfortable bed. I made a determined effort to spend more time on the paper, and as a result did no reading for my degree. Had the war not broken, I fear I should have made a poor showing in my finals. This did not particularly worry me, as a degree seemed to me the least important of the University’s offerings. Had I not been chained to my oar, I should have undoubtedly read more, though not, I think, for my degree. As it was, I read fairly widely, and, more important, learned a certain savoir-faire; learned how much I could drink, how not to be gauche with women, how to talk to people without being aggressive or embarrassed, and gained a measure of confidence which would have been impossible for me under any other form of education.