The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (13 page)

Read The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn Online

Authors: Nathaniel Philbrick

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century

“Oh, what good hearts they had!” remembered Wooden Leg, who was given a buffalo blanket by a ten-year-old girl. “I never can forget the generosity of Sitting Bull’s Hunkpapa Sioux on that day.”

It was not clear to anyone why the soldiers had attacked. Among the Lakota, young warriors in search of glory often did their best to confound the attempts of their more conservative leaders to rein them in. Crazy Horse theorized that President Grant, whom they called the “grandfather,” had run into similar problems with his army. “These white soldiers would rather shoot than work,” he said. “The grandfather cannot control his young men and you see the result.” The sad truth was that the white soldiers were acting under the explicit, if evasively delivered, orders of the grandfather.

One thing

was

clear, however. After years of watching his influence decline, Sitting Bull had finally come into his own. “He had come now into admiration by all Indians,” Wooden Leg remembered, “as a man whose medicine was good—that is, as a man having a kind heart and good judgment as to the best course of conduct.”

Sitting Bull, it seemed, had been right all along. The only policy that made any sense was to stay as far away as possible from the whites. If the soldiers were willing to attack a solitary village in winter, who knew what they might do to the thousands of Indians on the reservations. As the Cheyenne had learned back in 1864 at the brutal massacre called the Battle of Sand Creek, soldiers in search of a fight were perfectly capable of attacking a village of peaceful Indians, since they were always the easiest Indians to kill.

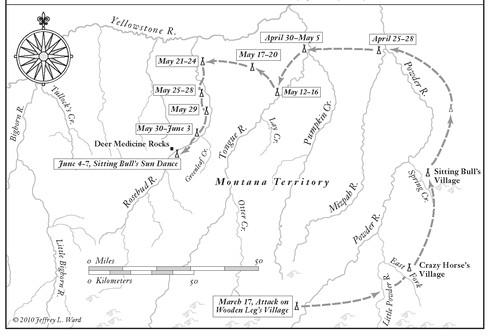

—SETTING BULL’S VILLAGE,

March 17-June 7, 1876

—

Sitting Bull determined that the best strategy was strength in numbers. As the village migrated north and west, he sent out runners to the agencies telling the Lakota to meet them on the Rosebud River. “We supposed that the combined camps would frighten off the soldiers,” Wooden Leg remembered. Keeping with the policy of the last few years, this was to be a defensive war. They would fight only if attacked first. To those young warriors, such as Wooden Leg, who longed to revenge themselves on the white soldiers, Sitting Bull and the other chiefs insisted on restraint. “They said that fighting wasted energy that ought to be applied in looking only for food and clothing,” Wooden Leg remembered.

By the end of April, the new spring grass had begun to appear. The buffalo were abundant, and when in early June they camped forty-five miles up the Rosebud from its junction with the Yellowstone, the village had grown to about 430 lodges, or more than three thousand Lakota and Cheyenne.

With hundreds, if not thousands, of Indians headed in their direction from the agencies to the east and south, hopes were high that this already sizable village might soon become one of the largest gatherings of Indians ever known on the northern plains. However, not all of those present were there under their own free will.

Kill Eagle was the fifty-six-year-old chief of the Blackfeet band of the Lakota. He lived at the Standing Rock Agency on the Missouri River, but that spring, the government failed to provide his people with the promised rations. He decided that he had no alternative but to leave the agency to hunt buffalo; otherwise his people would starve. He knew that the soldiers were planning a campaign against Sitting Bull, but he hoped to return to the agency before trouble started.

In May, he and twenty-six lodges were camped near the Tongue River when they were approached by warriors from Sitting Bull’s village. The warriors told him that he should “make haste” to Sitting Bull’s camp, where “they would make my heart glad.” Soon after his arrival at the village, he was presented with a roan horse and some buffalo robes. But when Kill Eagle decided it was time to leave, he and his followers soon discovered that they’d been lured into a trap. Almost instantly they were surrounded by Hunkpapa police, known as the

akicita

, who escorted them to the next campsite up the Rosebud River. Like it or not, the Blackfeet were about to attend Sitting Bull’s sun dance.

T

he sacred tree, with two hide cutouts of a man and a buffalo attached to the top, stood at the center of the sun dance lodge. Buffalo robes had been spread out around the tree, and Sitting Bull sat down with his back resting against the pole, his legs sticking straight out and his arms hanging down.

He’d vowed to give Wakan Tanka a “scarlet blanket”—fifty pieces of flesh from each arm. His adopted brother Jumping Bull was at his side, and using a razor-sharp awl, Jumping Bull began cutting Sitting Bull’s left arm, starting just above the wrist and working his way up toward the shoulder. Fifty times, he inserted the awl, pulled up the skin, and cut off a piece of flesh the size of a match head. Soon Sitting Bull’s arm was flowing with bright red blood as he cried to Wakan Tanka about how his people “wanted to be at peace with all, wanted plenty of food, wanted to live undisturbed in their own country.”

A few years before, Frank Grouard had endured a similar ordeal. “The pain became so intense,” he remembered, “it seemed to dart in streaks from the point where the small particles of flesh were cut off to every portion of my body, until at last a stream of untold agony was pouring back and forth from my arms to my heart.” Sitting Bull, however, betrayed no sign of physical discomfort; what consumed him was a tearful and urgent appeal for the welfare of his people.

Jumping Bull moved on to the right arm, and a half hour later, both of Sitting Bull’s punctured arms, as well as his hands and his fingers were covered in blood. He rose to his feet, and beneath a bright and punishing sun, his head encircled by a wreath of sage, he began to dance. For a day and a night, Sitting Bull danced, the blood coagulating into blackened scabs as the white plume of the eagle-bone whistle continued to bob up and down with each weary breath.

Around noon on the second day, after more than twenty-four hours without food and water, he began to stagger. Black Moon, Jumping Bull, and several others rushed to his side and carefully laid him down on the ground and sprinkled water on his face. He revived and whispered to Black Moon. Sitting Bull, it was announced, had seen a vision. Just below the searing disk of the sun, he had seen a large number of soldiers and horses, along with some Indians, falling upside down into a village “like grasshoppers.” He also heard a voice say, “These soldiers do not possess ears,” a traditional Lakota expression meaning that the soldiers refused to listen.

That day on the Rosebud, the Lakota and Cheyenne were joyful when they heard of Sitting Bull’s vision. They now knew they were to win a great victory against the white soldiers, who, as Sitting Bull had earlier predicted, were coming from the east.

On the other side of the Rosebud, on a rise of land about a mile to the west, were the Deer Medicine Rocks, also known as the Rock Writing Bluff. This collection of tall, flat-sided rocks was covered with petroglyphs that were reputed to change over time and foretell “anything important that will happen that year.” That day on the Rosebud, a new picture appeared on one of the stones depicting “a bunch of soldiers with their heads hanging down.”

The people were jubilant, but Sitting Bull’s vision contained a troubling coda. For the last decade, the Hunkpapa leader had urged his people to resist the temptation of reservation life. The promise of easy food and clothing was, he insisted, too good to be true. That day on the Rosebud, the voice in Sitting Bull’s sun dance vision said that even though the Indians would win a great victory, they must not take any of the normal spoils of war.

The defeat of the soldiers had been guaranteed by Wakan Tanka. But the battle was also, it turned out, a test. If the Lakota and Cheyenne were to see Sitting Bull’s sun dance vision to its proper conclusion, they must deny their desires for the material goods of the washichus.

CHAPTER 5

The Scout

O

n his deathbed in 1866, Libbie Custer’s father, Judge Daniel Bacon, made a most unsettling observation. “Armstrong was born a soldier,” he told his daughter, “and it is better even if you sorrow your life long that he die as he would wish, a soldier.” It was not a sentiment Libbie shared. “Oh Autie,” she wrote her husband during the Civil War, “we must die together. Better the hum-blest life together than the loftiest, divided.”

On the year of Judge Bacon’s deathbed exhortation, Custer visited a psychic in New York City who told him everything Libbie wanted to hear: He would have four children and live to “seventy or more.” The psychic also told him he was considering “changing businesses,” to either the railroads or mining, which happened to be exactly what Custer was contemplating at the time. Best of all, the fortune-teller confirmed the metaphysics of Custer luck: “I was always fortunate since the hour of my birth and always would be. My guardian angel has clung to my side since the day I left the cradle.”

Over the course of the intervening decade, almost none of the psychic’s predictions had come true. Libbie and Custer remained childless. It was just as well, Custer insisted. “How troublesome and embarrassing babies would be to us . . . ,” he wrote in 1868. “Our married life to me has been one unbroken sea of pleasure.”

Custer’s flirtation with business also did not pan out. By the winter of 1876, a poorly timed investment in a silver mine combined with a series of risky railroad stock speculations had brought him to the brink of financial disaster. That January, while he and Libbie were in New York City soaking up

Julius Caesar,

he pleaded with Generals Sheridan and Terry to extend his leave until April so that he could attend to his affairs; otherwise, he grimly claimed in a telegram, he stood to lose ten thousand dollars and would “be thrown into bankruptcy.” The extension was not forthcoming, and he and Libbie (who would not know the full extent of her husband’s financial woes until after his death) returned to Fort Lincoln.

In the end, he was neither the father of a growing brood of babies nor a budding millionaire; he was merely, as Judge Bacon had known all along, a soldier. But even that had been threatened during his run-in with President Grant. Quivering on the brink of professional and financial ruin, he was now headed, he fervently hoped, for a reunion with his guardian angel. If Terry would only give him the opportunity to find and catch the Indians, all would once again be well.

In the meantime, as he waited with his regiment beside the Powder River for Terry’s return from his meeting with Gibbon and the Montana Column on the Yellowstone, Custer spent every spare moment writing his next article for the

Galaxy

magazine. As Libbie had assured him, writing was his true destiny, and even though he was supposed to be directing preparations for the scout to the Tongue River, Custer sat in his tent composing an account of his early days in the Civil War. “It is now nearly midnight,” he wrote Libbie after a long day of writing capped by a simple dinner of bread drenched in syrup, “and I must go to bed, for reveille comes at three.”

At 9:50 p.m. on Friday, June 9, General Terry arrived back at the Powder River encampment in a driving rain. The next morning he met with the officers of the Seventh. He had big news. Major Marcus Reno—not, as had generally been assumed, Custer—would be leading the scout to the Tongue River.

The officers of the Seventh Cavalry didn’t know how to interpret this stunning bit of information. “It has been a subject of conversation among the officers why Genl Custer was not in command,” Lieutenant Edward Godfrey recorded in his journal, “but no solution yet has been arrived at.” For his part, Custer quickly did his best to make it sound as if he had never wanted to lead the mission in the first place. Mark Kellogg was a forty-three-year-old newspaper correspondent traveling with the Seventh Cavalry. “General Custer declined to take command of the scout . . . ,” Kellogg reported, “not believing that any Indians would be met with. . . . His opinion is that they are in bulk in the vicinity of the Rosebud range.”

In all probability, Custer had thought the scout was a fine idea when he saw it as a way to break free of Terry with the entire Right Wing of the Seventh Cavalry and find Sitting Bull. The Right Wing contained his six favorite companies in the regiment. With this group of loyal officers and their well-trained men, he could have done wonders. But now he must hand them over to Reno, who in his dutiful obedience to Terry’s misguided orders would only exhaust and discourage them.