The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (15 page)

Read The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn Online

Authors: Nathaniel Philbrick

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century

But as Boyer undoubtedly told Reno, the likelihood that the Indians were still anywhere near where they’d found them back in May was nil. A village of that size had to move every few days as the pony herd consumed the surrounding grass and the hunters ranged the country for game. Since almost three weeks had passed since the hostiles had been last sighted, and an Indian village could move as many as fifty miles a day, the hostile camp might be several hundred miles away by now.

Reno was, and still is, derided for his lack of experience fighting Indians. In actuality, he’d been chasing Indians since before Custer had even graduated from West Point. In 1860, he’d been assigned to Fort Walla Walla in the Oregon Territory, where he’d been ordered to investigate the whereabouts of a missing pioneer family. He found their mutilated bodies “pierced by numerous arrows” and set out in search of the Indians responsible for the attack. He and his men succeeded in surprising a nearby Native encampment, and in hand-to-hand combat he captured the two Snake warriors who were reputed to have killed the family. He’d done it more than a decade and a half before, but the fact remained that Reno knew how to pursue and find Indians.

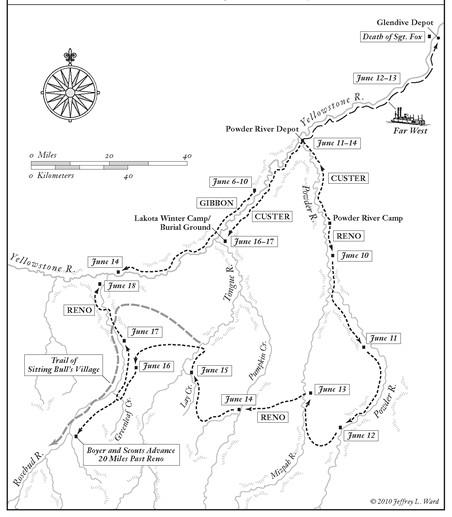

—RENO’S SCOUT,

June 10-18, 1876

—

Now that Reno was on the Tongue, it only made sense to cross the divide between them and the Rosebud, locate the May 27 village site, and, at the very least, identify in which direction the Lakota had headed next. Otherwise Terry’s subsequent move against the Indians was likely to come up with nothing. And besides, if they did happen to find the Indians, it could prove to be the opportunity of a lifetime. Back in 1860 he had taken an Indian village with a handful of men. Now he had more than three hundred of the cream of the Seventh Cavalry, and a Gatling gun to boot. It was a clear violation of Terry’s orders, but it was a violation that might make Reno’s career.

With Mitch Boyer leading the way, they crossed the Tongue River and headed west, toward the Rosebud.

O

n June 12, Grant Marsh and the

Far West

left the encampment on the mouth of the Powder and steamed down the Yellowstone to secure additional provisions at the depot on Glendive Creek, eighty-six miles to the east. Marsh offered to take along the reporter Mark Kellogg. It turned out to be the steamboat ride of Kellogg’s life. Over the last few days, the current on the river had, if anything, increased. “The Yellowstone is looming high,” Kellogg wrote in the

New York Herald,

“and its current is so swift, eddying and whirling as to create a seething sound like that of soft wind rustling in the tall grass.”

With a full head of steam and the current behind her, the

Far West

averaged an astonishing twenty-eight miles an hour during the three-hour trip to Glendive. “I think this proves the

Far West

a clipper to ‘go along,’ ” Kellogg wrote.

Marsh had brought a mailbag stuffed with the regiment’s personal and official correspondence. Sergeant Henry Fox of the Sixth Infantry and two of his men and one civilian were to take the mail in a small rowboat to Fort Buford near the Yellowstone’s confluence with the Missouri, a voyage of 126 miles. Fox was a twenty-two-year veteran of the army and the father of six children. He had just returned from Washington, D.C., where he’d filed his application for ordnance sergeant, considered to be “the crowning ambition of the most faithful old soldiers.”

His men brought the boat alongside the

Far West,

and with the heavy bag of mail draped on one arm, Fox stepped into the rowboat. The boiling waters of the Yellowstone pinned the little boat to the steamboat’s side, and it proved difficult for the soldiers to push away. As they struggled to separate the two craft, the rowboat began to tip, and before anyone could help them, the force of the river had capsized the boat, pitching all four of them into the Yellowstone.

The three younger men were experienced swimmers and were quickly rescued, but Sergeant Fox sank below the surface and was never seen again. There was much more death to come in the days ahead, but for Grant Marsh and the crew of the

Far West,

the tragedy began on June 12 with the drowning of Sergeant Fox, his lifeless body left to tumble and twist in watery freefall down the rushing river.

Soon after Fox’s disappearance, the mailbag was spotted floating between the

Far West

and shore. Before they could reach it, the bag had sunk once again, but with the aid of a boat hook, they were able to retrieve the sodden bag of letters. That night Marsh and Kellogg sat by the

Far West

’s stove, laboriously drying each piece of correspondence. The envelopes had become unsealed and the stamps had fallen off, but by the next morning, they’d succeeded in preserving these river-soaked, flame-crisped palimpsests of blurred ink. Custer was particularly appreciative of the lengths to which Kellogg had gone to save not only his letters to Libbie but also his

Galaxy

article, describing how the reporter had taken “special pains in drying it.”

Sure enough, about a week later, Custer’s letters had made their way down the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers to Libbie. In their hurried attempts to dry the contents of the mailbag, Marsh and Kellogg had apparently come close to destroying some of the correspondence they were attempting to save. Libbie’s earlier premonitions of doom had left her agonizingly sensitive to anything even remotely associated with her husband. In a missive Custer never got the chance to read, she reported, “All your letters are scorched.”

A

t 6 a.m. on Thursday, June 15, Custer and the Left Wing of the Seventh Cavalry crossed the Powder and headed up the south bank of the Yellowstone. About thirty miles to the west was the Tongue River, where they were to rendezvous in the next day or so with Reno and the Right Wing. For now General Terry remained on the

Far West,

which would meet them the following day on the mouth of the Tongue.

They had left behind about 150 men at the supply camp on the Powder. Most of them were infantrymen assigned to guard the provisions, but there were also the teamsters and their wagons, the unmounted troopers, and the members of Felix Vinatieri’s band, who had donated their pure white horses to the troopers in need of fresh mounts. For Custer, this was a stinging loss. The band had been an almost omnipresent part of his storied life in the West. Even in the subfreezing temperatures encountered at the Battle of the Washita, the band had played “Garry Owen” before the troopers charged into the village. It had been so cold that morning back in 1868 that what was supposed to have been a dramatic crescendo of horns had turned into a few strangled squawks and squeaks when the musicians’ spittle froze almost instantly in their instruments—but no matter. The band with all its gaiety and swagger had

been there

on the snowy plains. That morning the band members climbed up onto a hill beside the Yellowstone and played “Garry Owen” one last time. “It was something you’d never forget,” Private Windolph remembered.

In addition to the band, the troopers also left behind their sabers. In contrast to the Civil War, when sabers had been useful in hand-to-hand fighting, the cavalry in the West rarely found an opportunity to use these weapons against the Indians, who generally refused to engage them closely. Since the sabers were quite heavy, it was decided to leave them boxed on the Powder. It only made sense, but to be without a saber left many of the officers feeling naked and vulnerable. For a cavalryman, his meticulously crafted sword was what a coup stick was for a Lakota—a handheld object with tremendous symbolic power. At least one officer, Lieutenant Charles Camilus DeRudio, born in Belluno, Italy, could not bear to leave his saber behind (it was useful, he claimed, in killing rattlesnakes) and surreptitiously brought the weapon along in spite of the order.

That afternoon, after a dusty march over a low, grassless plain of sagebrush and cactus, they came upon the remains of a Lakota camp from the previous winter. The reporter Mark Kellogg judged the village to have been two miles long, with between twelve hundred and fifteen hundred tepees. Being a winter encampment, this was as close to a permanent settlement as was known among the nomadic Lakota. To protect their ponies during the brutal winter months, they had constructed shelters for the animals out of driftwood from the river.

Custer was at the head of the column, and soon after entering the abandoned village he came upon a human skull amid the charred remnants of a fire. “I halted to examine it,” he wrote Libbie, “and lying near by I found the uniform of a soldier. Evidently it was a cavalry uniform, as the buttons of the overcoat had ‘C’ on them, and the dress coat had the yellow cord of the cavalry uniform running through it. The skull was weather-beaten, and had evidently been there several months. All the circumstances went to show that the skull was that of some poor mortal who had been a prisoner in the hands of the savages, and who doubtless had been tortured to death, probably burned.” The Arikara scout Red Star watched Custer as he “stood still for some time” and stared down at the skull and scattered bones of the soldier. “All about [the soldier] were clubs and sticks,” Red Star remembered, “as though he had been beaten to death.”

The column next came upon the remains of a large Lakota burial ground. Some of the bodies had been tied to the branches of trees, others laid out on burial scaffolds. After having witnessed the grisly evidence of the unknown trooper’s torture and death, Custer appears to have been in the mood for revenge. They still had a few miles to go before reaching the Tongue, but it was here, at the Lakota burial ground beside the Yellowstone, that he decided to bivouac for the night.

That afternoon, Custer and his troopers systematically desecrated the graves. One of the scaffolds had been painted red and black, an indication, Red Star claimed, “of a brave man.” Custer ordered the African American interpreter, Isaiah Dorman, to take the wrappings off the warrior’s body. “As they turned the body about,” Red Star remembered, “they saw a wound partly healed just below the right shoulder. On the scaffold were little rawhide bags with horn spoons in them, partly made moccasins, etc.” Dorman ultimately hurled the body into the river, and since he was next seen fishing on the riverbank, Red Star surmised that he had used a portion of the warrior’s remains for bait.

Lieutenant Donald McIntosh’s G Company took a leading role in the desecration. McIntosh’s father had worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company in Quebec, Canada; his mother, Charlotte, was a direct descendant of Red Jacket, a famous Iroquois chief. His ancestry apparently did not prevent him from joining in the pillage. As McIntosh and his men pilfered trinkets from the bodies before throwing them in the river, at least one soldier cautioned the lieutenant “that G troop might be sorry for this.”

Foremost in the desecration, however, was the Custer clan, aided by Custer’s regimental adjutant, Lieutenant William Cooke. “Armstrong, Tom and I pulled down an Indian grave the other day,” Custer’s brother Boston happily reported to his mother. “Autie Reed got the bow with six arrows and a nice pair of moccasins which he intends taking home.”

Lieutenant Edward Godfrey was careful not to name names, but he was clearly shocked by the Custers’ behavior. “Several persons rode about exhibiting their trinkets with as much gusto as if they were trophies of their valor,” Godfrey wrote, “and showed no more concern for their desecration than if they had won them at a raffle. Ten days later I saw the bodies of these same persons dead, naked, and mutilated.” For his part, the interpreter Fred Gerard became convinced that the ultimate demise of the three Custer brothers, Autie Reed, and Lieutenant Cooke was “the vengeance of God that had overtaken them for this deed.”

That night the Custers were too busy being the Custer brothers to betray any concern about the possible consequences of their actions. “We all slept in the open air around the fire,” Custer wrote Libbie, “Tom and I under a [tent] fly, Bos and Autie Reed on the opposite side. Tom pelted Bos with sticks and clods of earth after he retired. I don’t know what we would do without Bos to tease.”

A

pproximately fifty-five miles to the southwest, Major Reno and the Right Wing had just made camp. All that day and until 11:30 that night, they had been carefully feeling their way across the divide to the Rosebud. They awoke the morning of June 17 to find themselves on the banks of a slender sliver of brown water beside what could only be described as a Native highway: an irregular road of furrowed dirt several hundred yards wide.

When moving from camp to camp, each Lakota and Cheyenne family loaded its goods onto a horse-drawn sledge known as a travois. The front ends of two tepee poles were lashed to either side of the horse, leaving the rear tips of the poles to drag along the ground behind. Tied between the poles was a rawhide hammock that could accommodate several hundred pounds of goods or an injured warrior or several small children and their puppies. Because of the flexibility of the slender poles, the travois provided a surprisingly smooth ride as it jounced easily over the uneven earth.