The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (31 page)

Read The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn Online

Authors: Nathaniel Philbrick

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century

Twelve-year-old Black Elk lay hidden in the timber near the river. “Just then,” he remembered, “I heard the bunch on the hillside to the west crying: ‘Hokahe!’ and make the tremolo. We heard also the eagle bone whistles. I knew from this shouting that the Indians were coming, for I could hear the thunder of the ponies charging.”

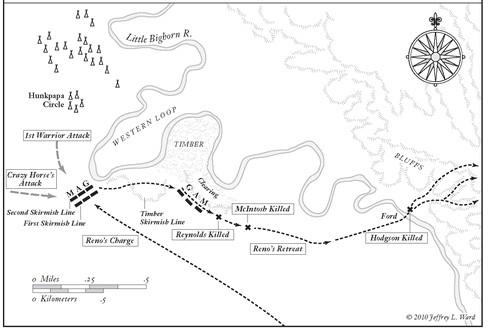

By this time, the soldiers’ skirmish line had pivoted to the left so as to face the growing threat to the west. Reno had been warned that the Indians were also threatening the horses in the timber to the east. He’d already sent Lieutenant McIntosh’s G Company into the woods to provide the animals with some protection; as a result, the ranks of the skirmish line had become distressingly thin. Fred Gerard watched as Reno, too, left the line for the timber. “I saw him put a bottle of whiskey to his mouth,” he remembered, “and drink the whole contents.”

It was time, Reno decided, to bring everyone into the timber. As Crazy Horse’s warriors charged toward them and the soldiers began to run for cover, Captain French, angered by the fact that no effort was being made to withdraw the battalion in a coordinated fashion, shouted, “Steady men! I will shoot the first man that turns his back to the enemy—fall back slowly. Keep up your fire!”

But it was little use. “The men ran into the timber pell mell,” remembered Fred Gerard, “and all resistance to the Sioux had ceased.”

Out in the middle of the skirmish line, about forty to fifty yards from the edge of the timber, Sergeant Miles O’Hara crumpled to the ground. He’d been hit and needed assistance. But no one was willing to go back for him. Private Edward Pigford never forgot the sergeant’s final words. “For God’s sake, don’t leave me,” O’Hara cried as the rest of the command ran for the safety of the trees.

B

ordering the western edge of the timber was a four-foot-deep trench carved out by one of the river’s divergences. It was ready-made for defense, and several of the scouts, including George Herendeen, planted themselves there along with the soldiers and began firing at the Indians out on the plain. “The Sioux would gallop in bunches,” Private Newell remembered, “and deliver their fire and then retreat, their places to be filled instantly by another bunch.”

—THE VALLEY FIGHT,

June 25, 1876

—

Captain Moylan turned to Lieutenant Varnum and said the men were beginning to run out of ammunition. It was time to bring up the horses so the soldiers could get the extra fifty rounds from their saddlebags. Varnum entered the timber, and after a strange encounter with Reno’s adjutant, Lieutenant Hodgson, who urgently asked him to check his horse for a nonexistent wound, Varnum brought A Company’s horses up to the trench’s edge. He’d just settled in beside the scout Charley Reynolds when the interpreter Fred Gerard offered Reynolds a sip from his flask. Reynolds had already experienced unsettling premonitions about the battle; he was also suffering from a painful infection on his hand. Varnum could not help but stare as the scout, famed for his quiet courage, struggled with trembling hands to drink from the flask. “I was paying more attention to that,” he later admitted, “than to the Indians.”

Varnum heard some men shouting behind him in the woods and went to investigate. Others quickly followed until only one man was left on the firing line—the scout George Herendeen.

T

wo years before, Herendeen had been part of what was called the Yellowstone Wagon Road and Prospecting Expedition: 150 men, most of them experienced Indian fighters, equipped with repeating rifles and even a few cannons, who ranged the Rosebud, Little Bighorn, and Bighorn river basins, looking for gold. It was an outrageous affront to Lakota sovereignty, and Sitting Bull had led several hundred warriors, including at one point Crazy Horse, against this cocksure group of frontiersmen.

Compared with the regiments of infantry and cavalry they had confronted before, this was a tiny group of washichus, and Sitting Bull had expected to send them quickly back to their home in Bozeman, Montana. However, in three different battles, one of them fought only a few miles from where they were now, the Lakota saw for the first time what a cadre of brave, experienced, and well-equipped gunfighters could do. “They appeared to go just where they wanted,” reported Johnnie Brughiere, who heard about the expedition from the Lakota. “[The Indians] could get nowhere near them without losing men or horses. . . . They could not understand it except on the theory that some new race of strangers had come into the country.”

On the afternoon of June 25, 1876, on the Little Bighorn, Herendeen saw that this patch of timber beside the river was an excellent place for Reno’s battalion to make a stand. With this trench to the west, the river to the east, and with soldiers strategically positioned around the timber’s periphery, they could hold out here for hours. But it was also becoming clear that the hundred or so men in the battalion “appeared to be without experience as soldiers.” Unless someone rose to the occasion and organized the three companies into a fighting unit, they would be overrun by the warriors.

Herendeen had just brought down a warrior and his horse when he realized that he was all by himself at the edge of the timber. “I then wondered,” he remembered, “where the men could be and why they did not come in and help stand off these Indians.” He soon found out where they were. In the middle of this crescent of cottonwoods, willows, and elders was a grassy clearing of approximately two to three acres. Instead of fighting off the Indians, Reno and his officers and men were apparently preparing to flee. Reno and Captain Moylan sat on their horses at the front of the emerging column as the soldiers scurried frantically through the timber in search of their horses. “All was confusion,” Gerard remembered, “and in trying to pick out their horses the language of the men was hasty and vigorous to say the least.”

Even though they were deep within the sun-dappled shade of these little woods, the sounds of the battle were terrific—“one continuous roar,” Private Newell remembered, as hundreds of warriors blew on their eagle-bone whistles and galloped on their whinnying, hoof-pounding ponies and either fired their rifles or shot arrows that cut through the leaves of the cottonwoods and sent puffy white seedpods raining down on them like snow. By this point, Reno had lost his straw hat and had tied a red bandanna around his head.

He was talking in sign language to the Arikara scout Bloody Knife, asking him if he knew “where the Indians were going.” Now that the Lakota and Cheyenne were unopposed, it was fairly obvious where they were going: They were steadily drawing toward them through the trees. “The Indians were using the woods as much as I was,” Reno remembered, “sheltering themselves and creeping up on me. . . . I knew I could not stay there unless I stayed forever.”

After helping the other Arikara capture as many horses as possible, Bloody Knife had rejoined the soldiers. Whether or not he was responsible for the deaths of Gall’s wives and children, he knew for a certainty that many of the warriors now approaching through the timber were Hunkpapa who knew him by sight.

There was a momentary lull in the Indians’ firing. Then, from about fifty yards away, a volley erupted from the trees. A bullet hit Bloody Knife in the back of the head, and with his arms thrown up into the sky, he toppled from his horse. At that moment, a soldier was shot through the stomach and cried out, “Oh! My God I have got it!”

The death of Bloody Knife seems to have badly flustered Reno, who later told Herendeen that the scout’s “blood and brains spattered over me.”

“Dismount!” he shouted before quickly countermanding the order: “Mount!”

By now, Reno’s horse was plunging wildly. Waving his six-shooter in his hand, his face smeared with blood and brains, Reno shouted, “Any of you men who wish to make your escape, follow me.”

CHAPTER 11

To the Hill

J

ust a half hour before, Wooden Leg had been asleep beside the Little Bighorn, dreaming that “a great crowd of people were making lots of noise.” He awoke to discover that his dream was real. Women and children were screaming and running. An old man cried, “Soldiers are here! Young men, go out and fight them.”

He and his brother started to run for their lodge. They passed mothers looking frantically for their children, and children looking just as frantically for their mothers. By the time he reached his family’s tepee, his father had already brought in his favorite horse. As his father placed a blanket on the horse’s back and prepared a rawhide bridle, Wooden Leg put on his best cloth shirt and a new pair of moccasins.

His father told him to hurry, but Wooden Leg refused to be rushed. He took out his tiny mirror and painted a blue-black circle around his face, then painted the interior of the circle red and yellow. He combed his hair and tied it back with a piece of buckskin. Finally, he mounted his pony and, with his six-shooter and powder horn in place, began to ride south through the village. There was so much dust that he couldn’t see far enough ahead to know where he was going, so he simply followed the other warriors ahead of him until he came to an island of trees full of soldiers. “Not many bullets were being sent back at them,” he remembered, “but thousands of arrows.”

He joined a group of Lakota warriors who had worked their way to the south of the timber. “Suddenly,” he remembered, “the hidden soldiers came tearing out on horseback.” Fearing attack, Wooden Leg and all those near him turned their horses and tried to escape from the onrushing troopers. “But soon we discovered they were not following us,” Wooden Leg recalled. “They were running away from us.”

E

very man for himself!” someone cried as Major Reno put the spurs to his horse and galloped out of the timber. Captain Thomas French couldn’t believe it. Just one minute before, Reno had assured him “he was going to fight.” And then, without so much as a bugle call to inform the battalion of what he was doing, he had fled, leaving those behind in wild confusion, many of them still looking for their horses, many of them not yet even aware that their commander had just bolted from the timber. French later claimed he considered stopping his commander with a bullet. “Although the idea flashed through my mind,” he wrote, “yet I did not dare to resort to murder—the latter I now believe would have been justifiable.”

French remembered being outraged by Reno’s behavior, but others saw the decision to flee from the woods as unavoidable. The Indians outnumbered them by more than five to one. The soldiers had already exhausted about half their ammunition. Where Custer and Benteen were at that moment was impossible to know. “Had Reno not made the move out of the river bottom when he did . . . ,” Private William Slaper insisted, “we could all have shared the fate of Custer and his men.”

But the most compelling reason to get out of the timber had to do with Reno himself. “When an enlisted man sees his commanding officer lose his head entirely . . . ,” Private Taylor wrote, “it would . . . demoralize anyone taught to breathe, almost, at the word of command.” Given the weakness of their leader and the strength of the enemy, the only sensible option was to get to higher ground on the other side of the river.

Even Captain French, despite his later claims, appears to have seen no other alternative at the time. Before the major’s unceremonious departure, Private Slaper remembered Reno turning to French and asking, “Well, Tom, what do you think of this?” According to Slaper, French responded, “I think we had better get out of here.”

It was not the fact that Reno chose to quit the timber that was unjustifiable; it was the way he did it. Instead of retreating in an organized fashion, Reno followed the example of the battalion’s spooked horses and ran.

O

nly belatedly did Lieutenant Varnum realize that the battalion had begun to retreat. “For God’s sake men . . . ,” he shouted. “There are enough of us here to whip the whole Sioux nation.” Varnum reluctantly mounted his horse and tried to join the exodus but was quickly shunted aside by the mass of galloping soldiers into a narrow, winding path through the brush. By the time he emerged from the woods, he was almost a quarter mile behind the leaders. The dust that was to make it impossible to see more than fifty feet ahead had not yet risen from the ground, and up ahead he could see “a heavy column” of troopers in the lead. Behind this group, the soldiers were scattered in twos and single file as they galloped through a gauntlet of warriors with Henry and Winchester repeaters laid across the pommels of their saddles, “pumping them into us.”