The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat (3 page)

Read The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat Online

Authors: Bob Drury,Tom Clavin

Yet this peaceful debarkation at Wonsan was the exception. Almost from the moment they waded ashore, the Marines of Fox Company encountered bloody, if sporadic, resistance along their two-hundred-mile slog north. The newspaper columnist Ambrose Bierce once noted that war was God's way of teaching Americans geography, and now obscure dots on the North Korean map with names like Hungnam and Hamhung and Koto-ri were proving his prescience. The company had lost good men in each of these places, and nearly a month earlier, during a two-day firelight at the Sudong Gorge, the Seventh Regiment encountered its first Chinese. They'd beaten them decisively, but afterward Fox had buried another eight Marines.

Fox Rifle Company was only a tiny component of the First Marine Division, which was itself just part of a pincer movement organized by General MacArthur. From his headquarters seven hundred miles across the Sea of Japan in occupied Tokyo, MacArthur commanded two separate United Nations columns moving inexorably north toward Manchuria. The columns were separated by fifty-five miles of what MacArthur described as the "merciless wasteland" of North Korea's mountains. In the western half of North Korea, near the Yellow Sea, the U.S. Eighth Army, augmented by South Korean, British, Australian, and Turkish troops-more than 120,000 combat soldiers in all-was overstretched in a thin line running from Seoul deep into the barren northern countryside.

Farther east on the Korean peninsula, MacArthur's X Corps, 35,000 strong, was also marching north, with eventual plans to meet the Eighth Army somewhere along the Yalu River, the country's northern border with China. Commanded by the Army's Major General Edward M. Almond, X Corps was a fusion of two South Korean Army divisions; a small commando unit of British Royal Marines; and a regimental combat team, put together from the U.S. Army's Seventh and Third Divisions. There was also the First Marine Division, the oldest, largest, and most decorated division in the Corps. The Marines considered General Almond as somewhat too adoring of MacArthur, and there was a tacit understanding among seasoned military observers both on the ground in Korea and back in Washington, D.C., that this fight belonged to the First Marine Division.

The First Marine Division was commanded by Major General Oliver Prince Smith and consisted of three infantry regiments-the First, the Fifth, and the Seventh-which were supported by the Eleventh, an artillery regiment. Each regiment consisted of about 3,500 men: three rifle battalions, each of approximately 1,000 men in three rifle companies of anywhere from 200 to 300 men. All told, General Smith had about 15,000 of his Marines along sixty-five miles of a rutted North Korean road that ran north to an enormous man-made lake the Americans called the Chosin Reservoir-a Japanese bastardization of the Korean name, Changjin-or the "frozen" Chosin.

MacArthur's plan was to sweep North Korea free of the communist dictator Kim Il Sung's fleeing North Korea People's Army all the way to the Yalu River. He boasted to reporters that once his troops had mopped up the last stragglers and diehards of Kim's army, the American boys would be home for Christmas. This would be a nice, short little war, wrapped up in five months. But even after the North Korean capital, Pyongyang, fell to the dogfaces of the Eighth Army, the Marines of Fox Company were hard-pressed to reconcile their own reality with MacArthur's optimism.

As Fox's crusty platoon sergeant Richard Danford had muttered after the brief, brutal scuffle at Sudong, "If these are the goddamn stragglers, don't even show me the diehards." Danford, at twentyseven, had a lot of hard bark on him, and he had learned through experience to trust little that came out of any general's mouth, particularly an Army general in Japan and away from the front line. He once heard a saying by a French politician, that war is too serious to be left to the generals. Now, there was a guy who knew what he was talking about. Danford figured that the Frenchman must have once served as an enlisted man.

Fox Company had caught only the ragged edges of the battle at Sudong. Other Marine companies took the brunt of the attacks by what were described as a few Chinese "diplomatic volunteers" who had sneaked across the Yalu River to aid the Koreans in the campaign against Western imperialism. Nonetheless, every American involved in the fight had been staggered by the disregard for life the Chinese displayed. Tales spread among the regiment of how an American machine-gun emplacement could take out half an enemy infantry company, and the remaining half would still keep charging. Someone even suggested that the Corps put together a special manual for fighting the "drug-addled Oriental." Moreover, paramount in every Marine's mind that November was a frightening question: Where were the rest of the Reds, and when were they coming?

A month earlier, the foreign minister of the People's Republic of China, Chou En-lai, had issued a public warning to the Americans to keep their distance from the Yalu. Mao Tse-tung, the Chinese leader, backed up his minister's threats by massing several armies of the Chinese Communist Force (CCF) on the far side of the river. This actually further inflamed MacArthur's atomic ego. After the landings at Inchon, in a meeting with President Truman on Wake Island in the northern Pacific, MacArthur brushed off Mao's move as "diplomatic blackmail."

"We are no longer fearful of their intervention," he told Truman. "If the Chinese tried to get down to Pyongyang, there would be the greatest slaughter."

Perhaps. But despite MacArthur's insistence that only a few Chinese had voluntarily crossed the Yalu-barely enough to make up a division-there were rumors running through the American lines that several CCF armies had in fact begun infiltrating North Korea in mid-October. These reports were not lost on the anxious Marine general Oliver Smith. Smith, a cautious man, had never shared MacArthur's expectation of a quick victory in North Korea-privately, he scoffed at the "home by Christmas baloney." He was certain that his Marines would face strong Chinese resistance west of the Chosin Reservoir as they pushed toward the Yalu. In a private dispatch to the Marine Corps commandant general, Clifton B. Cates, in Washington-a back-channel communication that enraged MacArthur when he learned of it-Smith pleaded for "someone in high authority who will make his mind up as to what is our goal." Smith apologized to Cates for the "pessimistic" tone of his letter but explained that to obey MacArthur's and Almond's instructions to push on with the First Division's flanks so exposed "was to simply get further out on a limb."

"I believe a winter campaign in the mountains of North Korea is too much to ask of the American soldier or Marine," Smith wrote, "and I doubt the feasibility of supplying troops in this area during the winter or providing for evacuation of sick and wounded. I feel you are entitled to know what our on-the-spot reaction is."

Smith noted in his letter that about half his fighting men were young, unseasoned reservists-despite the fact that when the First Marine Division had been hastily deployed to northeast Asia all the division's seventeen-year-olds were culled from the ranks to remain in Japan. Moreover, in many cases reservists with summer-camp experience-either one summer with seventy-two drills or two summers with thirty-six drills each-were deemed "combat ready" by dint of this training, despite the fact that they had never been to boot camp.

Before Sudong, no more than a handful of Marines in Fox Company had ever seen a Chinese soldier-and the others probably wouldn't have been able to tell the difference between a Chinese and a North Korean. Corporal Wayne Pickett, who at twenty-one was another of the "old men" in Fox, was, however, one of the few. He had served a tour in Shanghai as a seagoing Marine in 1947, and he told his buddies that their firefight at Sudong was a picnic compared with what he'd seen and heard at Shanghai. He added that they would sure as hell recognize a full force of "fighting Chinamen" when they met it. For one thing, the Chinese were taller, Pickett said, and a hell of a lot more robust and better armed than the human scarecrows still loyal to Kim Il Sung. Pickett also warned that the Chinese soldiers were veterans of Mao's civil war, and their fighting ability was not to be taken lightly. "And the ROKs damn well know that," he added.

As Pickett's stories spread, a few Marines in Fox Company thought back to a scene they had witnessed a couple of days after Sudong. While moving north, the outfit had passed a Republic of Korea Army unit marching south with a single Chinese prisoner. The Americans didn't have much faith in the fighting ability of most ROKs to begin with, but at the time more than a few Marines were shaken by the overt fear their South Korean allies exhibited at the mere presence of this shackled Shina-jen, or Chinesu, in their midst.

Nonetheless, by the time Fox Company lined up for its Thanksgiving dinner, they hadn't seen a hostile Chinese in the four weeks since Sudong. The Chinese had simply disappeared, and a buoyant feeling was slowly returning to the company-a sense that Christmas day 1950 might indeed be celebrated in dining rooms and at kitchen tables in Duluth and San Antonio and Pittsburgh, in Los Angeles and Miami and the Bronx.

2

During the first six months of the Korean War, its ebb and flow had pushed Fox Company to a remote, windswept tableland 210 miles north of the 38th Parallel, which had been established as the border between the two Koreas after World War II. The locals called it Kaema-kowon, the roof of the Korean peninsula.

In the sixteenth century, the first European missionaries and traders painted a romantic portrait of this sawtooth terrain, likening it to a sea in a heavy gale. For weeks, Fox had been traversing this knotted ground, up one desolate mountain, down the next, hiking cold and wet toward the Yalu-and these exhausted men did not compose any lyrical odes to the place. Some Marines in Fox Company had come to consider the situation a cruel game, and with nothing to lose they began playing it themselves. At dusk they would search the compass points and pick out the highest, coldest-looking hills. Then they would wager on which one they would be sent to hold for the night.

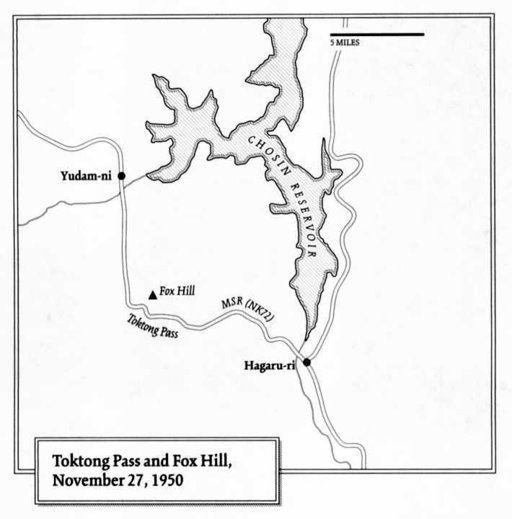

Now, on the morning of November 27, 1950, they were on the move again. The knoll Fox was abandoning after Thanksgiving rose west of the village of Hagaru-ri, which to the Americans resembled nothing so much as an old Klondike mining camp with its dilapidated houses packed close around newly erected canvas tents. The village was situated atop a muddy, triangular plateau whose southern terminus was a broad field crammed with more rows of American tents, supply trains, and fuel and ammunition dumps. On the edge of this clearing Marine engineers operated five Caterpillar tractors day and night under fixed floodlights, chugging to and fro, carving a crude airstrip out of the frozen earth. Scuttlebutt had it inside Hagaru-ri's defensive perimeter that Fox was preparing to move up a winding, twelve-foot-wide dirt road the Americans had designated Main Service Road NK72, or simply the MSR.

Most of the men believed they would be traveling the fourteen miles north to another tiny village, Yudam-ni, which was in a floodplain between two rivers and the northwestern tip of the Chosin Reservoir. There they assumed they would rejoin the bulk of their Seventh Regiment and its commanding officer, Colonel Homer Litzenberg Jr., a stubborn, impatient Dutchman known as "Blitzen Litzen." Litzenberg's regiment was part of a force of 8,400 thatalong with most of Colonel Raymond Murray's Fifth Regiment and three artillery battalions of the Eleventh Regiment-was the tip of X Corps' spear. Eight miles to the east, across the reservoir, 2,550 GIs who were part of two Army battalions were also positioned to storm north, locked and loaded, anticipating MacArthur's order to commence the final push to the Yalu.

But as Fox Company assembled outside the Battalion Command Post in Hagaru-ri, word filtered down that they were headed not to the reservoir, but instead to Toktong Pass-seven miles north, midway between Hagaru-ri and Yudam-ni. There they were to dig in along one of the lower ridgelines of the highest mountain in the area, the 5,454-foot Toktong-san, which overlooked the MSR where it cut through the pass. It was the only road into or out of the Chosin.

This order to essentially babysit at a bottleneck did not sit well with Fox Company. In fact, the Marines could not comprehend it. The North Koreans had been on the run for ten weeks, and by this stage in the war even Hagaru-ri was considered a safe enough rear area to have its own PX, even if its stock was limited to Tootsie Rolls and shoe polish. Moreover, Marines did not retreat, so the very idea that Litzenberg's and Murray's rear supply route needed guarding was ludicrous. The enlisted men of Fox would have much preferred to push on farther north to Yudam-ni, lest they cede bragging rights to some undeserving outfit. Baker Company of the regiment's First Battalion was already boasting about the carpet of corpses it had left in the hilltops, gorges, and draws around Sudong. This was more than nettlesome, particularly because in Fox's opinion Baker Company wouldn't know its ass from a hole in the ground.

Naturally, the Marines blamed this strange turn of events-as they blamed most things-on MacArthur's inconceivable decision to place X Corps under the overall command of an Army general: Almond. Rivalries among the Marines themselves may have been spirited, if good natured. By contrast, there was no love lost at all between the Corps and the pogue doggies-a pejorative slang term Marines originally had applied to anyone with a soft, rear-area job but which by now was used to describe any dogface in the Army, a branch of the service that the jarheads deemed so thick with deadwood it should have been declared a fire hazard. This was another reason for Fox Company to add Almond's name to their already long shit list.