The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat (2 page)

Read The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat Online

Authors: Bob Drury,Tom Clavin

A BAR man from the Second Platoon watched them: maybe a hundred or so soldiers no more than three hundred yards away, climbing a parallel peak. They were hopping along the ridgeline like jackrabbits, and he was so impressed with their agility and the sharp cut of their uniforms-hell, even their backpacks looked impossibly squared away-that he initially thought they might be some hotshot Marine outfit he didn't recognize.

But when his squad reached the top of the ridge they were stopped in their tracks by the disconcerting sight of a lone Chinese officer standing atop a giant boulder and dragging casually on a cigarette. At the Americans' approach he flicked his butt in their direction, jumped from the rock, and disappeared over the reverse slope. The Marines had been too stunned by his presence to shoot him. When they reached the boulder they found field telephone wires running down the cleft in the ridgeline. A couple of men unsheathed K-bar knives to cut the wires, and someone said, "The bastard's been watching us the whole time."

From the top of the hill the Marines of Fox Company could again see Dog Company, fighting for its life far to the west. Not a few men wondered what the hell was happening.

Meanwhile, down in the creek bed, one of the wounded Marines cried for help. A Navy corpsman squatting next to Captain Zorn made a move to rise from the ditch, but the company's gunnery sergeant shouldered him back to the ground. Because of the Chinese machine-gun fire, any attempt at rescue seemed futile. But Sergeant Peach decided to chance it. He scooped up the corpsman's medical kit and took off. Zorn and the few Marines behind him opened up with covering fire. Peach made the creek bed. The Americans near Zorn whooped with admiration. Peach was unlashing the med kit from his shoulder when he was stitched across the face by machine-gun fire. The top of his skull seemed to lift off his head, as if pulled by invisible wires.

Captain Zorn ordered a counterattack, and the remaining Chinese fled up the hill, leaving perhaps fifty of their dead strewn across the road. The rest of the day became a long, tense standoff as the Marines and Chinese regulars attempted to outflank each other on the ridgelines. Sniper fire and the occasional pop of small mortar rounds echoed off the hills. Zorn radioed Division and then ordered Fox Company to dig in for the night as he and his staff laid plans for a dawn attack.

But by sunrise the Chinese had vanished, and the Marines of Fox were left to wonder if this disappearance was permanent, or if they had just taken part in the opening salvo of World War III.

THE HILL

DAY ONE

NOVEMBER 27, 1950

1

The Americans moved in slow motion, as if their boots were sticking to the frozen sludge of snow, ice, and mud. They had been dug in on this godforsaken North Korean hillside for less than forty-eight hours, yet when the 192 officers and enlisted men of Fox Company, Second Battalion, Seventh Regiment were ordered to fall in, gear up, and move out, their mood became almost wistful-or what passed for wistful in the United States Marines.

Just past sunrise, Dick Bonelli, a nineteen-year-old private first class, crawled from his foxhole, stomped some warmth into his swollen feet, and took a look at the new line replacements. Most of these men-boys, really-were reservists who had joined the company within the past couple of weeks. He knew few of their names. "Greenhorns," he spat. "Don't know how good they had it sitting up here fat and happy."

The words came out in a voice so gravelly you could walk on it, all the more menacing because of Bonelli's tough New York City accent. The sky began to spit snow as he packed his kit and continued to gripe. Corporal Howard Koone, Bonelli's twenty-year-old fire team leader from the Second Squad, Third Platoon, shot him a sideways glance. Fat and happy? Two men from the outfit had been wounded on a recon patrol the previous night. But Koone, a taciturn Muskogee Indian from southern Michigan, let it slide. Bonelli had been in a foul mood since Thanksgiving, when his bowels were roiled by the frozen turkey he had wolfed down outside the battalion mess.

At first the holiday feast served three days earlier had seemed a welcome respite from the greasy canned bacon, lumpy powdered milk, and gristly beef turdlets that the mess cooks seemed to specialize in. But at least a third of the outfit had picked up the trots from eating the ice-cold candied sweet potatoes, sausage stuffing, and young toms smothered in gravy-served hot, of course, but flash-frozen to their tin trays by the time the Marines took the meals back to foxholes that felt more like meat lockers. Elongated strips of frozen diarrhea now littered the trench latrine.

Bonelli threw his pack over his shoulders. "Off to kill more shambos in some other shithole for God, country, and Dugout Doug," he said. A couple of guys choked out a laugh at his scornful reference to the Supreme Allied Commander, General Douglas MacArthur.

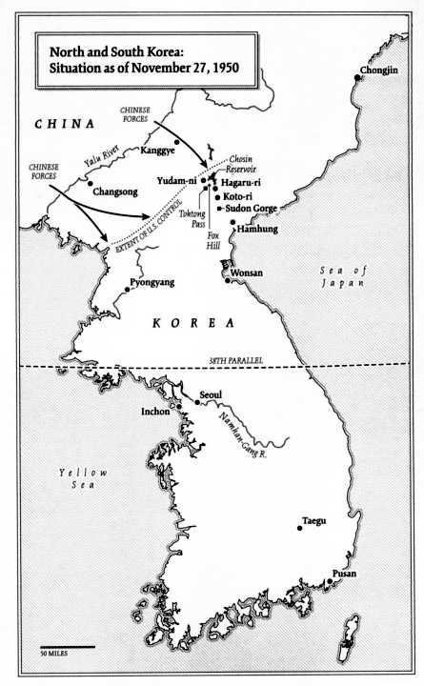

With his jet-black pompadour, high cheekbones, and (often broken) Roman nose, Bonelli could have been cast as one of the quickdraw artists stalking Gregory Peck in The Gunfighter, the hit movie being shown on a continuous loop in the holds of Navy troopships steaming from California to northeast Asia. This was apt. Cowboys versus outlaws was an overriding American theme in 1950, almost as fashionable as cowboys versus communists. It was the year when Alger Hiss was convicted and Klaus Fuchs was arrested for spying for the Soviet Union, and an obscure senator from Wisconsin named Joseph McCarthy propelled himself into the headlines by charging that the State Department employed more than two hundred communist agents. It was the year President Harry S. Truman authorized the construction of the first hydrogen bomb, and Germany had settled into separate countries. It was the year when Winston Churchill warned in the House of Commons of a "looming World War III," and across the Atlantic more than 100,000 U.S. National Guardsmen and reservists were recalled to active duty. Half a decade after the hottest war in history, the world in 1950 was on the cusp of George Orwell's "cold war." Though Orwell had died ten months earlier, his phrase was destined to live on, not least in the craggy mountains of North Korea.

But Dick Bonelli and the enlisted men of Fox Company were not much given to geopolitical strategy. Theirs was a tactical clash, not even dignified (as they noticed) by an official declaration of war; it had been designated, instead, a United Nations "police action." It was a dirty little conflict in a faraway Asian country the size of Florida, a "Hermit Kingdom" that most Americans couldn't even find on a map. The fighting was on foot and deadly: hilltop to hilltop, ridgeline to ridgeline. Whatever small plateau of land the Americans controlled at any given moment constituted their total zone of influence, and was ceded again to the enemy once they had departed.

The deadly Browning automatic rifle-the BAR-was the weapon of choice for the strongest Marines, and one of Fox Company's BAR men was Warren McClure, a young private first class from Missouri. Just that morning, he had been introduced to his new assistant, Roger Gonzales, a reservist and private first class from Los Angeles. Gonzales had been in Korea less than a week. "Forget the flag, patriotism, and the Reds," McClure told him. "We never own any territory; we're just renting. You're out here for the fight and the adventure." Gonzales hung on the old-timer's every word. McClure was all of twenty-one.

Dick Bonelli wouldn't have argued with McClure's advice. He had been born in Manhattan's Hell's Kitchen and raised in the Bronx, and fighting and adventures were a way of life for him as the son of an Italian bus driver growing up in an Irish neighborhood. He had even beaten up one of his high school social science teachers who had dared suggest that Bonelli was descended from an ape. His truculent attitude had caught up to him sixteen months earlier, when he was arrested for "borrowing" a stranger's car and was offered two options by the Bronx district attorney: the armed forces or an indictment for grand larceny.

Bonelli was a tough kid, and the Marine Corps, which by 1950 had become America's warrior elite, was a natural fit for him. The farm boys and cowhands of the Army's nascent Ranger units could still remember their origins as lowly mule skinners, the Navy's SEALs were still only envisioned by former World War II frogmen, and the Green Berets did not yet exist. But the Marines-there was an outfit.

Then, as now, it was the frontline Marine rifleman who preoccupied the strategists and tacticians at Quantico in Virginia, the acclaimed Warfighting Laboratory-specifically, how to infuse in every man in every rifle company the Corps' basic doctrine that battle had nothing to do with strength of armaments or technology or any theoretical factors dreamed up by intellectuals. Instead, according to the Marine Corps Manual, warfare was a clash of opposing wills, "an extreme trial of moral and physical strength and stamina." To its acolytes, the Marine Corps was no less than a secular religion-Jesuits with guns-grounded in a training regimen and an ethos that relied on a historical narrative of comradeship and brotherhood in arms stretching over 150 years. In short, if a man wanted to be part of America's toughest lineup, he had best join the institution that had fought at the Halls of Montezuma and Tripoli, Belleau Wood and Guadalcanal, Tarawa and Iwo Jima. And Dick Bonelli certainly wanted to fight. He may have been pushed into the Corps by the law, but now, as he put it, he would "run through hell in a gasoline suit to find the gook party."

From the beginning of the war, American soldiers had been approached by Korean children who pointed at them and said something that sounded like "Me gook." Actually, the Korean word gook means "country," and the children's use of the phrase mee-gook was probably a complimentary reference to the United States as a "beautiful country." However, among the Americans the term gook soon took on a pejorative sense, meaning any Asian, especially any enemy Asian. Bonelli's constant refrain since the landings at Inchon had been, "When do we get the gook party started?" It was now Fox Company's catchphrase after every ambush and firefight: Hey, Bonelli, big enough party for you?

The men of the company had attracted their share of fighting. Admittedly, one month earlier they had endured a ten-day "sail to nowhere" around the Korean peninsula. They had boarded flatbottomed "landing ships, tank" (LSTs) at Inchon on the west coast and had steamed to an unopposed landing near the mined seaport of Wonsan in the northeast. To their humiliation, they had been beaten there by a flight carrying Bob Hope and his USO dancing girls.