The Last Supper (17 page)

Authors: Rachel Cusk

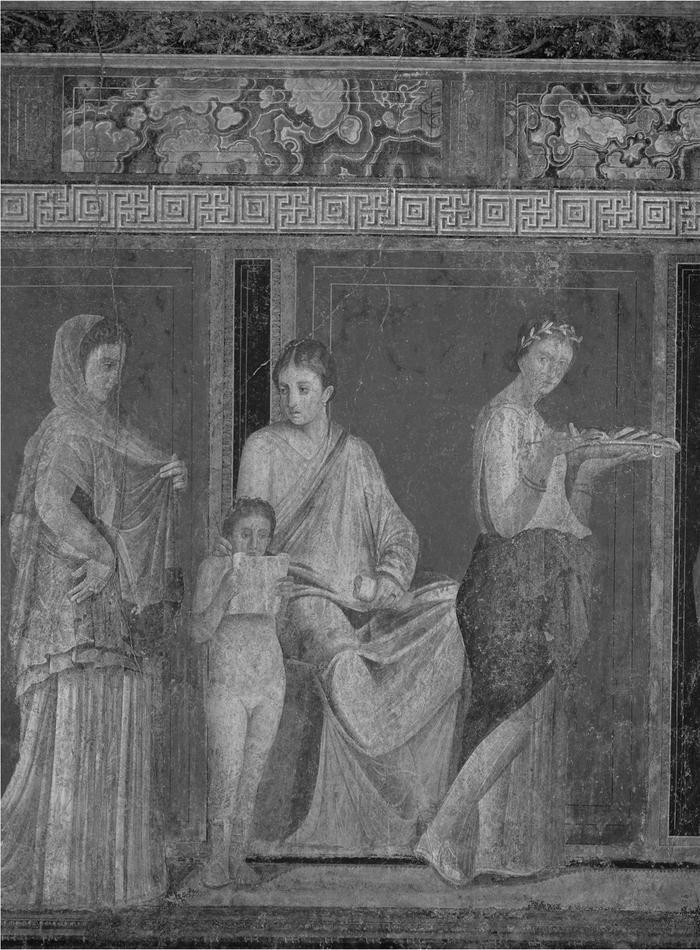

The Catechism with a Young Girl Reading and the Initiate Making an

Offering

, North Wall, Oecus 5,

c

.60–50

BC

(fresco) by Roman

But the messianic master stands before it, chanting. He is terrible, exultant, malign. His students gaze at him with trance-like expressions. Their eyes are the blank, elliptical eyes of marble goddesses.

*

We have booked a room in Piano di Sorrento. The man at the door bows courteously at our arrival. He introduces himself: he is Paolo. He is so small and dapper and cool. We are so hot, and rimed with pumice dust. The door from the street, where the air-conditioned coaches thunder along the narrow road to Sorrento, was deceiving: behind it there is a garden, green and shady, with peaches growing on the trees.

All the same, we are a little shocked by the change of climate: by the heat, the frenzy, the crowded precipitate hillsides plunging down into the sea, the pell-mell succession of the squalid and the sublime, the feeling everywhere of cramp, of confinement, of the imprecision of desire meeting the exactitude of possibility. We go down to the beach at Castellammare to swim: it is so crowded on the narrow gritty stretch that the children have to sit on our laps amidst the cigarette butts, and in the rubbish-strewn water it’s standing room only. The bus

can barely squeeze back up the narrow road. The cars inch past one another, snagging on the hairpin bends. This is a world so vertical that the horizontal is a form of luxury. I sit on the bus with my eyes shut, dreaming of prairies, of my flat East Anglian childhood.

It is Paolo’s ancestral home that we are staying in. Once it was quiet here, on a hilltop above the sea, but now the house is impacted in the vertical tundra of development that covers the whole northern coast of the peninsula. It is not particularly ugly, this modern geology. It is just that in its fundamental properties it has the qualities of an anxiety dream. Paolo shows us the family chapel, a light, whitewashed little room on the first floor whose windows look out on the rooftops and the community football pitch. There is a plaster statue of the red-cheeked Virgin, and spindly wooden chairs in rows, facing the altar. He shows us the dining room and the suite of drawing rooms, with their gold brocade sofas and family portraits and great ceramic urns standing in the shadows. The shutters are closed against the sun. The marble floors are silent underfoot. It is like a museum, except that the present moment is checked at the front door. The world does not flow around these objects: instead there is Paolo, attenuated and leather-skinned, faintly saturnine, with his small, polished, bony head like the head on a Roman coin. Paolo’s wife comes in. She is a Veronese madonna, yellow-haired, decked in gold, rather excitable, who moves rapidly in a shoal of little dogs. She tells us that they have just had a grand wedding here. It was their daughter who was married. Things are a little chaotic, a little mad. The house is upside down. She asks how long we are staying, and what we have been doing: she shudders at the mention of Pompeii. She herself is from the north. She doesn’t like it here, in this cacophonous dust-bowl under the volcano. Most of the time she and Paolo live in Rome.

In the evening we take the bus along the coast. The sun is going down, and the sky flames with pink. The sea is soft and

silent, with a milk-white sheen. An eerie calmness settles on the belle-époque villas on their promontories of rust-coloured rock when the light leaves their faces. They take on strange, savage shapes, with their plumes of palm trees and dilapidated balustrades. A drift of lights heaps itself around the bay. Over the water we can see Naples, smoking like a mound of embers. The cone of the volcano is dark, effaced, as though these lights were rivers of lava it had discharged itself. We get off the bus and walk down through a dank staircase in the rock, all the way down through the cliff until we come out far below, beside the water. There is a tiny beach, and a jetty. There is nobody here. We take off our clothes and jump off the jetty into the water. The water is warm, silky: it seems not to wet us but to coat us with its milky sheen. It is a relief, at last, to swim, but the water withholds something from us. It has the same impenetrable quality as everything else, a feeling of mystery, almost of secrecy, as though it were not fully present to us. It is half-violated, this beautiful bay with its rubbish-strewn water and shroud of polluted air. It is like a violated woman who refuses to give up her secret.

We walk back up through the cliff and sit down in the restaurant at the top. It has a round terrace that abuts the precipice. Gulls land on the balustrade and look sharply at the tourists through the dusk. There are English people here, middle-aged men and women with brick-red skin who say please and thank you in their native tongue, for it is easier to be transported to the Bay of Naples than to form the sounds that compose the word

grazie

. The men sit silently with their pints of lager, their beefy red arms folded across their chests. The women are silent too. They hold their handbags on their laps and take tiny sips from their glasses of sherry. They seem to disapprove of something, in their neat blouses and skirts, their rigid helmets of hair. They look down on the violated woman succumbing to her trance of night. In their way they have a deep secrecy of their own. Is it their own bodies they disapprove of, for being transported here? At least their minds remain theirs, refusing to say

buongiorno

and

grazie

. What are their bodies, that they can just be lifted out of one place and set down in another? Where will they find themselves next? The waiters are exquisitely gentle with these people. They refill the pint glasses at the merest nod. They straighten the nearby tables and chairs so that the deracinated bodies will not be buffeted or bruised. They like them: I have been told this by Italians, how much they like the English. They don’t care what language the please and thank you come in. Apparently most Italians never say thank you at all. The word is like a pearl, falling from those reticent English lips. It is clear that the waiters will stop at nothing to prise out as many of them as they can.

*

The next day we go down to the harbour at Sorrento, to take the boat to Capri. But there is no boat to Capri: the boatmen are on strike. We pace about the harbour fretfully, conferring. The town lies above in its fortress of rock. It is full of big, brassy hotels and souvenir shops and red-skinned tourists. Beyond it lies the green headland and beyond that the sea. I had wanted to go to Capri: I had decided on it as the turning point in our travels, the gold coin at the bottom of the pool that I needed to grasp to be released. It had seemed important to me, to touch it, to grasp it. How else could I understand our experiences unless I gave them a shape, an arc? Standing in the hot, crowded harbour I feel my artistry being unpicked. I feel my conception faltering, breaking up. I feel the question forming itself, the question that has not yet been asked, that I meant never to be asked again: what are we doing here?

A man approaches. He tells us that there is a boat, a single boat that will take us around the headland to Positano, on the Amalfi coast. I do not particularly want to go to Positano. I want to go to Capri. I want to see the Carthusian monastery, and Tiberius’s villa. I want to go to an island, from where I can look back on the last three months and make the decisive stroke that will complete them. It will be no good, going to Positano. It will be artificial. It will not be

satisfying. It will ruin everything with its artificiality, its lack of truth. Nevertheless, we get on the boat. There is, after all, nowhere else to go. We have come to the end. I will not go back up to Sorrento and stare through the windows of souvenir shops beneath the hammering sun. It is preferable to be on the water, in limbo, chugging around the headland to get to the other side. From Positano we can take a bus back over the middle to Paolo’s. It will be a little circle. It will be tourism for halfwits, for imbeciles.

The boat trip takes an hour. We watch the green tufted headland; we watch the sea. We see Capri, dimly, through the

polluted haze. Now and then huge speedboats roar by, or skirmish in their own foam. Positano comes into view, and steadily advances across the bobbing water. Its pink and white houses climb steeply up the hillside in the sun. The shore is full of bodies. They lie, basking like lizards. They watch our approach through their countless pairs of sunglasses. The whole spectacle seems to move up and down, though it is the boat that moves. But the town seems unhinged, unfixed. It seems like a figment of someone’s imagination.

We get off. The children fling away their shoes and run on to the dark, gritty sand. Then they turn round and run straight back, alarmed. The sand is so hot it has burned their feet. And it seems we must pay to be on the beach. It is fifteen euros each. We stand at the fence and look into the ranks of loungers and parasols where the community basks inscrutable behind its sunglasses. The heat is infernal; the torpid water rolls noiselessly on the shore. We have been trapped, cornered. The boat chugs away across the water; far above the road scribbles among the hilltops. We are seized suddenly by bravado: we pay the money and establish ourselves in the front row, among the millionaires and divas and the honeymooning couples. We flick up our parasol; we buy lemon ices in tall glasses; we don our sunglasses and examine our neighbours with unconscionable thoroughness.

There is a couple nearby, American, young and blonde and groomed as gods. The boy has the faux-heroic look of a Kennedy, with his snub patrician face and sculpted nimbus of hair. The girl is classical, farouche as a Jamesian heroine: she discloses her body in its spotless white swimming costume shyly, like a marble nymph. The boy’s costume is white too. They look like brother and sister, though it is clear they are on honeymoon. They lie side by side on their loungers, glancing around self-consciously, estranged somehow, in spite of their common aesthetic purpose. It is as though they are impersonating a pair of rich East Coast newlyweds, but there is no reason to think that that is not what they are. The boy gets up and

goes alone into the sea. He swims out a little way and then returns and hangs just offshore. He keeps his head above the water. He tosses his hair. Then the girl comes to the water and steps carefully in. She is so self-conscious she can barely swim. She is as though very old, or ill. She reaches the boy and half-embraces him in the water. I see him avert his face: he is worried she will wet his hair. He pushes her away, sending her back to shore. Then for a long time he stays out there, tossing his hair this way and that, so frantically that I wonder whether he is mad. The girl sits on her lounger with a strange little smile on her face.

The children play in the water; the sun is high, and the sea is a furnace of glitter. The light seems to liquidise everything, the people and the parasols, the boats and houses and green hills behind. They grow molten, indistinct. Only sound is left, the sucking of the sea, the drone of voices, the shrieks of gulls and the distant thrumming of engines. I close my eyes and the question is there. What am I doing here? It is as though I have carried a picture in my mind that has suddenly been atomised, has separated into a million particles. In its place there is the world, atonal, indiscriminate, random. It is late June. Tomorrow we are turning round. We are starting our journey home. But I have broken something here, on the journey’s floor, at its southernmost point. Something has been mislaid. I open my eyes and there is the honeymooning couple. Did they steal it from me, the feeling of understanding? For though I look and look at them I can make no sense of them at all. I need Raphael to paint them for me. I need an artist, to refine crude life into something I can understand.

Later we take the bus back, along the inland road that winds through the mountains. The settlements of the coast vanish behind a bend. There is only the sky above and the sea below. It is so green up here, so wild. It seems to exult in its own freedom. We pass through out-of-the-way places where women hang their clothes on washing lines. Then we are in green again, in tangled thickets that run freely up and over the peaks, run

beneath the dome of the sky. The water seems to watch them from below, these wild hills. It watches them like a mother watches a running child. It embraces their feet. It seems, somehow, to be smiling.