The Latte Rebellion (15 page)

Read The Latte Rebellion Online

Authors: Sarah Jamila Stevenson

Tags: #young adult, #teen fiction, #fiction, #teen, #teenager, #multicultural, #diversity, #ethnic, #drama, #coming-of-age novel

“Asha, you’re doing fine,” she said, reassuringly, but I could see worry lines creasing the center of her forehead. “If I were in your shoes, I—”

“Asha! Oh, my God. I had no idea it was going to be like this. I mean, this is

crazy

. But you’re doing so

awesome

.” It was Shay Saintmarie. She wriggled her slender cheerleader frame into the row behind me and gave me a breathless hug.

“Thanks,” I said, a little taken aback.

“You really are,” she said again, and smiled. “We’re all behind you. Well, mostly.” She glanced at the back of the room and I followed her gaze. Of course. Kaelyn. “Anyway, I better go to the little girls’ room while I still can, but I just wanted to tell you that we’ve got your back.”

“Okay,” I said, confused. Who was “we”? And why would Kaelyn even bother to come? But before I could try to figure it out, Miranda was standing where Shay had been a moment ago, grinning from ear to ear. My parents looked from one girl to the other, flabbergasted.

“Girl, you have got this in the

bag

. I am so proud of you.” Then she sobered. “I’m sorry about Carey, though.”

“Yeah, that was … really tough.” My eyes felt a little watery just thinking about it. I smiled weakly. “I’m glad you’re here.”

“You think I would miss this?” Miranda said incredulously. “Hell, no. Though I’m going to need some caffeine if I want to get through the rest of it. Want me to get you a coffee or something?”

“Maybe a soda,” I said. Coffee was the last thing I wanted.

Miranda smiled sympathetically and hurried out the main doors. My dad took the opportunity to put one arm around my shoulders and steer me over toward a quieter corner of the room, my mom bringing up the rear.

“What you don’t need is for people to be distracting you right now,” he said testily. “Don’t they have any respect for your situation? You’re literally on trial. They should be giving you some space.” He looked around, everywhere but at me, frowning.

“Daniel,” my mom said, warningly. “This isn’t easy for Asha. Let her friends support her.”

My dad crossed his arms and leaned against the wall. His dark hair, which had been neatly slicked back when we left the house this morning, was disheveled and falling into his face as if he’d been the one on trial. “If they’re really your friends, they should have kept you out of this mess in the first place,” he mumbled.

“Dad, that’s not fair. There wasn’t anything they could have done,” I said. I was starting to wonder what kind of trouble

he’d

gotten into at my age. But I didn’t ask. Today wasn’t about him, and it wasn’t about whatever might have happened thirty years ago.

In fact, inside I was smiling a tiny victorious smile. If he was angry at other people, or resentful about some mysterious event in his past, then he

wasn’t

angry at me. At least, not entirely. And maybe, by the time this was over, I’d have a chance of convincing him that I’d done what I thought was the right thing. That I hadn’t been irresponsible deliberately, just to flout everything he’d ever tried to teach me about the real world, about being a “sensible young woman focused on my academic future.” He might still be irritated with me, and he might not agree, but if he came out of it realizing not everything was my fault, I’d at least have that small victory. I’d know he didn’t think I’d failed.

Even if I was expelled.

The next day was a blur. I spent most of the time trying to put on a brave front, trying not to think about what Carey had said to me over the phone, trying not to think about the fact that we’d yelled at each other and I’d hung up on her. She took the bus to school; I drove there alone. We avoided each other’s eyes during passing periods and gave each other the silent treatment during classes. Carey would be leaning forward attentively and taking copious notes, and I’d be across the room in my assigned seat, painfully conscious of her ignoring me. I’m not afraid to admit that it sucked big-time.

At lunch, Carey was conspicuously absent.

“You just missed her. She said she was going to the library to do research for that history paper,” Miranda said, eyebrows raised. “She seemed stressed out; is everything okay?”

I pressed my lips together. Obviously Carey hadn’t mentioned our argument, and I was torn about whether to confide in Miranda or make excuses. Miranda was looking at me, but not expectantly, just curiously. Her wide eyes were rimmed with black eyeliner, setting off her braided hair, which she had dyed black over the weekend.

“You know, your hair looks good like that,” I said.

“You’re avoiding the question,” she said. “I know something’s up. You’re doing that grimacing thing.”

I felt my face crumple, and I blinked back tears that suddenly threatened to flood out over my cheeks and onto my lunch. I took a few deep breaths to try to suck the tears back in by sheer willpower. “Carey and I had a minor disagreement regarding the future of the Rebellion.”

“Way to be detached.” Miranda put her hand on my arm. “What really happened?”

I leaned my head back, staring out the window at the wispy gray clouds as if I could just fly away and start fresh somewhere far from here, without all this baggage, without the stupid Rebellion, even without Carey.

“Nothing. Everything,” I said, shakily. “She said she couldn’t be part of the Rebellion anymore.”

“She did?” Miranda looked stunned. “So … what did you say?”

“Well, there’s nothing I can do to stop her. But I told her it wasn’t fair, and that I thought we were having fun doing this together. And she said it

wasn’t

that fun for her. That’s when I hung up.”

“You hung up, huh?” Miranda gave a cynical smile. “Well … I can understand why you’d be kinda pissed.”

“I know!” I sniffled a little. “It was like we were kids again, just throwing ourselves into some random project. Like when we started our own magazine in seventh grade.”

“I can totally see the two of you doing that.”

“It was called

Fast Times at Ashmont Junior High

.” A few tears sneaked out and I stifled an angry sob, my chest aching. I wanted to take all the copies I had of

Fast Times

and throw them right in Carey’s face. I wanted her to remember what it was like, what

this

was supposed to be like.

Miranda squeezed my arm.

“I wish I’d known you guys in junior high,” she said, clearly trying to distract me. “Thank God we left Nebraska. I mean,

you

guys remember. I showed up freshman year all skinny, with those braces and that hideous perm. And my brother’s hand-me-down flannels.”

“It seems so far away.” I wiped away a stray tear. “I mean, look at you now.” With her traffic-stopping braids and model’s tall frame, I could hardly even picture what she’d been like before.

“

And

the kids in Nebraska all thought I was Asian, so they’d chant ‘ching chang chong’ at me like I was some kind of idiot.” Miranda smiled that twist of a smile again.

“Well, your eyes are kind of almond-shaped,” I said. And then I couldn’t help it; a small grin sneaked onto my face.

“What?”

“Sorry … I know it’s not funny.” I paused. “The thing is, when Carey and I were in elementary school, people used to insist we were Mexican.”

“But neither of you looks even remotely Hispanic in any way,” Miranda said.

“Of course not.” I rolled my eyes. “But people see what they want to see.”

“Because you’re brown and they can’t tell what you are.” Miranda picked at her cheese sandwich. “You know, this is why the Latte Rebellion is a

good

thing. It’ll open people’s eyes. I mean, it’s not like we just automatically identify with whichever group we look the most like.”

“Yeah.” I nodded. “Not to mention, ethnicity isn’t anybody’s whole story anyway.” Thank God. I didn’t need anybody trying to figure out who I was based on being mixed up, though “mixed up” wasn’t a bad description.

“Maybe,” Miranda continued, “what people said to you in elementary school made this inevitable.”

“Huh. Maybe,” I said. It did make sense. Maybe Carey and I

did

do this for a reason, even if it was subconscious.

“That’s what’ll be so great about the rally,” Miranda added, perking up a bit. “It’ll raise awareness, and the poetry slam will bring in even more people. I’m looking forward to it.” She paused, then asked, “Are you even going to go, since … ?”

“Of course,” I said, a little sourly. “I promised to give the introduction. Paper bag and all.” Then something occurred to me. Carey wasn’t going, but that didn’t mean I had to mope around just because she’d decided to blow me off. I was free to do whatever I wanted now.

“Actually, I think I

will

stay for the poetry slam after all. I might as well, since …” We sat there without speaking for a few minutes, eating potato chips. I shook my head a little at the thought of going to the rally without Carey. We’d been inseparable since sixth grade, but that was a long time ago. Maybe we needed a break. It was an uncomfortable thought, one that made me feel like the ground was sliding away underneath me, like I was freefalling down a hillside without any clue where I would end up.

“I’m glad you’re going,” Miranda said. She patted my arm again. “We’ll have fun.”

I relaxed a little despite myself, and managed to wrestle my thoughts to a more positive place. There were other Latte Rebels in the sea. Or in the coffee pot, maybe. And at the rally, I’d be meeting lots of them.

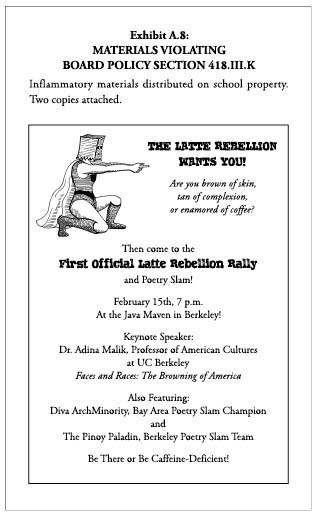

On Saturday around five, I fired up the Geezer and headed for Miranda’s house. I was fidgety with excitement, despite the collapse of my original plans with Carey. After all the afternoons spent plastering rally posters around town and driving into Oakland, Berkeley, and San Francisco to poster the college campuses there, and all the meetings where I had to sit there feeling like a fool with a paper bag over my head, today would be Agent Alpha’s biggest moment yet.

Not only that, Thad would be there to witness it. Even if I was keeping my secret identity under wraps, just knowing he was going to be in the audience made my stomach a little fluttery, and not in a bad way.

I pulled up to Miranda’s house, a small, tidy bungalow in an older neighborhood full of tall, winter-bare trees. She was already waiting outside on the porch and slid gracefully into the car, putting her crocheted black bag at her feet.

“I cannot

believe

today is finally here,” she said. We grinned at each other. She’d helped me put up all the posters, along with Darla, and of course it was her artwork gracing most of them. “Gun it, Jeeves.”

I obliged and peeled out of her driveway with a slight screech of tires, which set us off giggling. Most of the way there, we yelled along with the lyrics of really stupid disco songs on her MP3 player as the farm fields and green shrubby hills rolled past in the orange light of the setting sun. We passed through a few smaller towns before finally reaching the more densely built-up areas and increased car traffic that signaled the outskirts of the San Francisco Bay Area. The last ten minutes of the drive, we turned off the music. I rehearsed my introductory remarks, and we speculated on what the speaker was going to talk about and whether either of us would ever have the guts to go onstage at a poetry slam (no for me; maybe for Miranda).

When we got there, I parked the car in a busy garage in downtown Berkeley, and we walked to the café along streets crowded with vendors, cars, bicycles, loiterers, shoppers, and, of course, students. I was starting to get really nervous now, and we stepped into a florist’s shop next to the Java Maven so I could put on my paper bag face. Miranda was going to be a regular, inconspicuous audience member. Lucky her.

“I’m not sure I can do this,” I said. “I seriously might throw up.”

“Think of it as a rehearsal for your graduation speech,” Miranda said, smiling gently.

“Oh, sure.” But at least then—

if

I got to speak—I’d do it as myself. I wouldn’t have to represent for the whole Rebellion. I looked at my feet. “God, my stomach hurts.”

“You’ll be great. They all love you already. Agent Alpha is a legend. You could go up there and do the chicken dance and they’d go nuts.”

I tried to smile as I pulled the paper bag over my head. My stomach was still going crazy when we slipped through the door into the Java Maven’s main room.

Special event today,

the sign on the door said, scotch-taped to a poster for the Latte Rebellion Rally. I gulped and strode toward the scarred wooden podium at the front of the room.

It’s just like the Latte Rebellion meetings at Mocha Loco,

I told myself.

No big deal.

Except for all the people.

Stark fluorescent lighting flooded the room and illuminated at least a hundred, maybe a hundred and fifty, coffee-guzzling onlookers with expectant faces—sitting at little round tables, piled onto extra chairs, and lining the walls at the back of the large rectangular space. Most of them were wearing Rebellion T-shirts, both the original and the illicit versions. The baristas looked frazzled but pleased at the continuing stream of customers, and people were chattering happily and loudly.

That is, until the door closed behind me and people turned to see who it was. When they saw my trademark paper-bag mask and Latte Rebellion T-shirt (original, of course), the room slowly went quiet. The wave of silence started from the tables nearest the door and spread gradually inward, heads swiveling and conversations abruptly ending. It was exactly like one of my recurring nightmares, where I have to give an oral report in class but I’m missing a critical item of clothing, like my pants.

At least this time, I actually

was

wearing pants.

Miranda slid quietly past me—as we’d agreed, she was pretending not to know me while I was in Agent Alpha drag—and took up a standing position halfway back, next to a window. I tried not to look at all the staring faces as I choked down my nervousness and walked to the front of the room.

It was so packed that I didn’t have a hope of seeing Thad, if he was even here. I hadn’t realized it until that moment, but I was counting on him being there to give me an extra boost of moral support, even if he didn’t know he was doing it. Even if he didn’t know I was Agent Alpha.

As I got closer I could see Leonard, conspicuous in his tan Rebellion shirt and black pinstriped pants. He motioned me to a seat marked with a paper sign reading “Reserved for Rebellion Staff.” He was going to introduce me, and then I’d make a thankfully short speech to open the evening’s events.

In the seat next to me was an intense-looking woman with rich dark-brown skin, short salt-and-pepper hair, and elaborate dangly earrings. She was carrying a sheaf of note cards and a pile of brochures advertising

Uncut, Undried: The Complexity of Race in America.

Clearly this was Dr. Adina Malik, the keynote speaker. She cast her sharp gaze on me when I sat down, and one side of her mouth quirked upward in a smile as she took in my paper bag head.

“I take it you’re one of the founders of this little grassroots movement,” she said.

“Yes, I’m, uh …” I swallowed. Did I want to blow my cover, even for the keynote speaker? This wasn’t a joke anymore—Dr. Malik was taking it seriously. So it didn’t feel quite right to introduce myself as Agent Alpha.

Are you scared?

said a taunting little voice inside me.

It wasn’t like I’d see her again. People were talking now, and nobody was in our immediate radius to overhear, which I confirmed with a furtive glance around us.

“I’m Asha,” I finally said, in a near-whisper, feeling like my stomach was going to drop out of the bottom of my shoes. “Thank you for coming to speak.” I hoped my voice didn’t sound too distinctive.

“Why, you’re very welcome,” she said, smiling slightly. “It’s not every day that I get to be in on the ground floor of a unique group like this. You know, your ideas are really quite interesting.”

“Thanks; we’ve enjoyed the experience.” I didn’t know what else to say.

“I’m sure you have enjoyed it,” she said. “I’m sure you have. Oh, to be young again and on the fighting front …” She fanned out her note cards, looking wistful. I had no idea what she was talking about. All I knew was, Leonard was going up to the podium to do his thing and I was up next.

“Attention Rebellion Sympathizers,” he said, pulling the microphone closer. His voice boomed out with a squeal of feedback and the room quickly went silent again. There were clinks of coffee cups and the rustling of papers, but nobody spoke.