The Latte Rebellion (17 page)

Read The Latte Rebellion Online

Authors: Sarah Jamila Stevenson

Tags: #young adult, #teen fiction, #fiction, #teen, #teenager, #multicultural, #diversity, #ethnic, #drama, #coming-of-age novel

But Miranda and I grabbed each other and screamed along with the crowd, laughing to ourselves because that figure was unmistakable.

Diva ArchMinority was none other than Bridget’s roommate, she of the myriad anime action figures: Darla.

I rubbed my temples, trying to ignore the shrill-voiced girl yelling into the microphone about injustice and single motherhood. After Darla had showed up looking like a Japanese pop star crossed with Bugs Bunny in drag, we had endured over an hour of ranting, raving, and rhyming. Greg had already had his moment to shine, but he was being upstaged by all the people who seemed to spout one-liner after one-liner, making the crowd hoot and holler.

Miranda had watched his entire performance with her chin cupped in one hand, her expression rapt and considering. I had a bizarre vision of a double date with the four of us, Greg in his stupid hat and me in my paper bag mask, and shuddered.

Miranda glanced at me. She jerked her head toward the door and raised her eyebrows questioningly. I nodded, relieved. Poetry slams were

not

for me, I decided. It was just too much noise and bluster, completely different from when we were busy creating the website or going to planning meetings; at least then there was a tangible product. And it didn’t give me a splitting headache.

I put on my sweater, glancing at Thad regretfully. He saw that Miranda and I were getting ready to leave and put his hand up to his ear in a gesture I couldn’t for the life of me interpret. Was this some kind of Berkeley-style goodbye wave? An activist “fight the power” thing? Should I do the same thing in return—put my fist to my ear?

Miranda poked me and pulled her phone out of her pocket, waving it in front of my face.

God, I’m such a dork.

I smiled weakly and nodded. I wanted, really badly, to lean back in and return the hug Thad had given me when I first walked in, but a girl with a bullring-pierced nose and red knitted snood had already honed in on our seats. Plus, to be honest, I didn’t know if any attempts at flirting would be successful, since it was something I was frustratingly incompetent at. Or maybe he was just thinking of me as, say, a little sister—horrors! So I settled for a wave—a regular one—and what I hoped was a sultry smile. I’d have to find out later, over the phone, if it had had the intended effect.

The following Tuesday night, I called Carey. It had been one of the weirdest weeks of my life, and not just because of the rally (surreal as it was to see Darla in something other than an anime T-shirt).

The only other time Carey and I had been angry at each other for this long was in eighth grade, when we both had a crush on Roy Anderson and I decided to do something about it by asking him to the Halloween dance. She was so mad, I got the ice-queen treatment for eight days straight.

But on the night of the dance, Roy tried to freak-dance with me, called me a bitch when I wouldn’t, and then proceeded to swap spit all evening with the school’s most notorious slut. Carey saw the whole thing and, needless to say, both our crushes ended that night. We both vowed—over root beer floats at the Denny’s across the street, after leaving the dance early—never to let anything (or anybody) so stupid come between us again.

And I was thinking about our vow when I called, silly as it was. Just like then, I didn’t want to be fighting with her. I wanted us to be part of the Rebellion together, but failing that, I wanted to at least put an end to the silent treatment. I really missed Carey. In all the sappiest, most sentimental friendship-movie ways imaginable, I missed her.

“Hello?” She picked up the phone, sounding distracted. I heard her put one hand over the receiver and hiss, “Roddy, I’m

on the phone

. Go sit at the table and read your book,

please.

”

“Hey, it’s me,” I said, flopping back onto the bed.

“Oh.”

I couldn’t quite tell what that “oh” meant. It could have been “oh” as in “oh, it’s you; what the hell do you want?” Or it might have been “oh” as in “oh, I’m surprised you called, yet also profoundly overjoyed.” I swallowed, my throat dry, and turned onto my side, pulling my knees up to my chest.

“‘Oh’?” I said. “Is that it?”

“What did you

want

me to say?” she said, tiredly.

“I don’t know,” I said, clenching my jaw. “You know, you could have called me.”

“

You

could have called

me

,” she pointed out, logically.

“Look, I’m sorry I hung up on you,” I said. “I was just … mad because I didn’t want you to quit, that’s all. This is stupid. All of it’s stupid,” I said in a rush.

She was quiet for a minute. “I know you don’t think it’s stupid. You don’t have to say that on my account.”

I sighed and stretched my legs back out. “Look, I know you’re busy and you have a lot of extra crap dumped on you. I’m sorry I tried to make you keep going. I just thought … especially with Leonard involved, you might want to …”

“Oh,

Leonard,

” she said. “I barely had time to talk to him this week. But he visited a few days ago to bring me coffee when I was studying.”

“That’s … nice,” I said. Strangely, I meant it.

“Yeah, but I told him I couldn’t do anything more with the Rebellion.”

I blinked. I hadn’t expected that. I’d expected her to give him some kind of noncommittal answer, to try to string him along. And here she was being

honest

with him. “Was he mad?”

“I don’t think so. He seemed okay. It’s kind of hard to know what he’s thinking, you know?”

I laughed stiffly. “No kidding.”

“Anyway, he wanted me to come to the rally too, but I had soccer practice and work. He said fine, and we talked on Sunday. He told me how everything went. He said you gave a good speech.” I heard Carey put her hand over the mouthpiece again. “

Not now!

Just a minute.” One of her brothers was whining shrilly.

“Sounds like you have your hands full,” I said. I couldn’t exactly argue with her excuses, but I felt a little forlorn. And I couldn’t help wondering whether she was being as honest with me as she was with Leonard. “I guess I’ll let you go.”

“Okay. Sorry,” she said. “My brothers are going crazy. They got into Mom’s Valentine candy.”

“Oh,” I said. “Well, I guess I should do homework, anyway. Okay if I call you later to check calculus answers?”

“Sure,” she said neutrally. I didn’t know what she was thinking, and it was a strange, unfamiliar, uncomfortable feeling. “Talk to you later.”

“Bye.” I flipped my phone shut and tossed it toward the foot of the bed. I felt tears start and wiped them away, frustrated. My conversation with Carey wasn’t exactly what I’d been hoping for. I’d pictured us laughing like normal by the end of the call, after I’d updated her on the rally and Thad, and then we’d be saying goodbye with promises to sit together at lunch again and study for our physics test on Friday. Instead, it had been awkward and weird, and I wasn’t even sure anything had been resolved.

I was at the kitchen table doing French homework when my mother came in from the living room and handed me the home phone. It was about a week and a half after the rally, but the ongoing tedium of my life made it seem like months had gone by. I glanced up, wondering if it was Thad, and if so, why he hadn’t just called my cell. Or maybe it was Carey, who had thawed a little since our last phone conversation.

“Nani wants to talk to you,” Mom said. “I told her about that boy you met. The one from UC Berkeley.”

I groaned. “

Why

did you have to tell her? Nothing’s even going on with him.” Not yet, anyway.

“Just talk to her.” My mother patted me on the shoulder and smiled wryly. “She’s curious. She wants to know what’s going on in your life. You remind her of herself at your age.”

God, how could that even be? I apprehensively brought the phone to my ear and said, “Nani?”

“Hullo

beti

, I don’t want to interrupt your studies for too long, but I wanted to tell you something. Your mother was telling me how … busy you’ve been.”

Oh, no. Cue the “why haven’t you called?” guilt trip, or worse, the nosy interrogation about Thad and the inevitable questions about whether there were any “handsome college-bound Indian boys” at school that I could be lusting after instead. I fielded that question at least once a month, and my answer was the same—why do they have to be Indian? Couldn’t they just be cute and college-bound? What did their ethnicity matter? Just because I was Indian—half, at that—did not mean I was destined to marry Anil Prakash, who wore wire-rimmed glasses, plaid shirts, and tan slacks to school every day and could barely talk to a girl without stammering. Or Bhabu “Bob” Kumar, who was a meathead baseball jock. Honestly.

I braced myself for what was no doubt coming, clenching my fingers around the phone receiver.

“I’m very proud of you, Asha, but I have to admit I’m a little worried about you. You’re always so busy. Too busy to talk to your old Nani, eh?” Her voice was soft with concern.

Oh no, here it comes.

“I know you’re nearly eighteen now, but you’re still a girl to me. And … I want you to remember while you’re still young that life isn’t all about work. You’re doing very, very well.” I heard her sigh heavily. “Please just be sure to take a break every now and then. Call your friends. See a film.”

I did a double-take. This wasn’t what I’d been expecting. Not at all.

“It worries me when I talk to your mother and all she tells me is how much you’ve been studying and studying and studying. I know your parents push you a bit, especially your father, but don’t forget to stop and take a breath, okay, dear?”

“Um … yes?” I said, a little dazedly.

“And Asha

beti

, truly, you can always call me. It doesn’t have to be a holiday. I would be thrilled to hear all about your adventures with your friends. When I was young, I just adored walking with my girlfriends through the shops downtown, eating hot fried snacks from the vendors and holding the beautiful saris up to our faces … I’ll never forget those days. They’re as valuable to me as the time I spent in the teachers’ college.”

Nani went on in that vein for a few minutes. By the time we hung up, I’d hardly said a word.

She was right. I’d never spent much time thinking about how hard my parents pushed me. It was just a fact of life. Carey dealt with the same thing, though she put a lot more pressure on herself than I did. But what I couldn’t tell Nani was that the Rebellion was giving me that outlet, that feeling that there was more to my life than manic test prep and petty competition for grades.

I could hardly get my mind around the fact that, of all people, it was my elderly Nani who didn’t seem to mind that I wanted my life to be about more than just a perfect report card, the perfect college, and the perfect list of achievements.

At least there was

somebody

in my life who wasn’t telling me I needed to buckle down and get serious.

A couple of weeks afterward, I was sitting in the living room after dinner with my parents, half-watching TV while catching up on reading for most of my classes. I was in a pretty good mood, since I’d just gotten off the phone with Thad. Unfortunately, the news show my parents were watching was all sordid and depressing, and I was aching to change the channel to mindless entertainment like Celebrity Dance-Off. But no such luck.

“… report that the gunman, who has taken five international students hostage, is Raymond Gretch, also a student at the college,” chirped the news reporter.

“Horrible,” my mother said. My dad

hmph

ed in agreement. I tried to block it out and focus on

Invisible Man

.

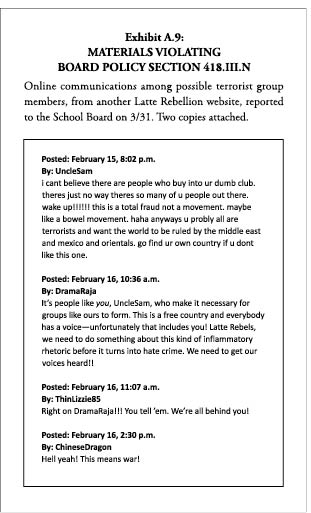

“Though it isn’t known whether Gretch is personally acquainted with the hostages, a search of his Blue Sky, Indiana, apartment turned up printouts of several of the students’ schedules, copies of class assignments, and other evidence that Gretch had been following them around the Blue Sky College campus, including flyers for the Model United Nations and an organization called the Latte Rebellion, advertised as a club for students of mixed race.”

My head jerked up involuntarily, and in a second I was just as glued to the TV as my parents were, hardly able to believe what I was hearing. The newscaster continued rattling off speculations about the gunman, but didn’t mention anything more about the Latte Rebellion. Still, I was in shock. We’d made the news! Sure, it was bad news, but the bad stuff wasn’t about

us

. And now we were practically a household name. I didn’t know what to think, but it felt like the bottom had dropped out of my stomach.

Then my mother said, “This Latte Rebellion nonsense again. Asha, I’m not sure you should be wearing that shirt. They sound … extreme.”

“Troublemakers, Lalita,” my dad grunted, and turned the sound up on the television. “Kids acting up.”

“It’s just a club,” I said, suddenly worried. What else had they heard? Had I missed something? “Didn’t I tell you about it? I went to that … uh … lecture on the weekend and it seemed fine. They had a Berkeley professor.”

“Berkeley professor.” My mom looked thoughtful for a minute. “Still, Asha, these so-called ‘movements’ can get out of hand. When extremist fringe groups start to form …”

“Mom, believe me, the Rebellion is just a club to promote acceptance of mixed ethnicity. It is not an ‘extremist group.’” I looked up from my English notebook. “Trust me on this one.”