The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

ALSO BY MICHAEL HIRSH

Pararescue: The Skill and Courage of the Elite 106th Rescue Wing—the True Story of an Incredible Rescue at Sea and the Heroes Who Pulled It Off

None Braver: U.S. Air Force Pararescuemen in the War on Terrorism

Your Other Left! Punch Lines from the Front Lines

Terri: The Truth

(with Michael Schiavo)

FOR THREE PEOPLE WHO CHANGED MY LIFE

My aunt and uncle

Rochelle and Sam Sola

And my friend

Marvin Zimmerman

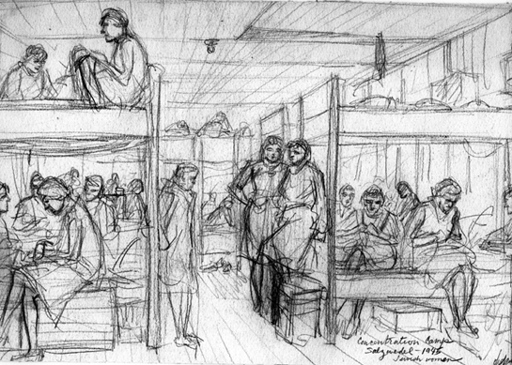

Jewish women prisoners in one of the barracks at the Salzwedel concentration camp sketched by 84th Infantry Division artist historian Sergeant Walter Chapman shortly after the division liberated the camp

.

ON LIBERATION

What did we, camp prisoners, perceive of the moment? The SS suddenly left. We are locked inside the barracks. An airplane circles menacingly, close to the roof; hundreds of women crouch on barren floors and contemplate Imminent Death, who is no stranger—and a few do hope and so they speak. Shots are heard sporadically—the jailkeeper’s plane vanishes and then silence, long silence. Suddenly out of nowhere, it seemed, or out of another world, some mystical beings appear in shiny armor at the gate. All the prisoners able to move, cry and laugh, embrace each other and shout—“Americans! Americans!” The gates, the doors open, “Americans! We are free!” The words are shouted in innumerable languages. It forms one unified choir:

LIFE!

… in the name of all of us who were freed, please accept the thanks for our last 37 years of life!

GOD BLESS AMERICA!

Mrs. Alice Kranzthor Fulop, age 81

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

April 22, 1982

A letter discovered by the author in the archives of the U.S. Army Center of Military History written to thank the 84th Infantry Division Railsplitters for the liberation of Salzwedel concentration camp, where she survived with her daughter, Nicole Martha Kranzthor

.

CONTENTS

Introduction: How Do You Prepare to See That?

6.

Mere Death Was Not Bad Enough for the Nazis

7.

Ike Knew This Would Be Denied

8.

Buchenwald: This Ain’t No Place I Wanna Be

9.

Gardelegen: Even the Good Germans Had Blood on Their Hands

10.

Bergen-Belsen: A Monstrous Spectacle Set to Music

11.

I Start Crying and I Can’t Talk Anymore

12.

Landsberg: The Kaufering Camps

13.

Dachau: Shock Beyond Belief

14.

They’re Killing Jews—Who Cares?

15.

Gusen-Mauthausen: How Sadistic Can You Be?

16.

You Are Still Individually and Collectively Responsible

17.

After the War, and Long After the War

INTRODUCTION

HOW DO YOU PREPARE TO SEE THAT?

I

n the final months of World War II, as American soldiers pushed the German army east toward the advancing Russians, the GIs began to discover—and to liberate—dozens upon dozens of camps large and small filled with the multitudes imprisoned by the Nazis. Some had been shipped to the camps to serve as slaves, to dig tunnels into mountains, there to build war machines for the Reich. Others had been shipped from camp to camp for one purpose only: to keep them from falling into the hands of the advancing Allied forces.

The prisoners who are the focus of this book had been liberated by the Americans, British, and Canadians. (The Russians liberated the notorious camps in Poland.) They had been consigned to death; the manner was, for all practical purposes, irrelevant.

They were marched to death, worked to death, starved to death, dehydrated to death, frozen to death, sickened to death, gassed to death, and sometimes shot to death—although this was not a preferred method, but only because bullets were not cost-effective. It also wasn’t enough that the victims of the Nazis died; they were always humiliated and usually dehumanized and tormented before death came.

The deaths occurred not just in a handful of concentration camps whose names are familiar to almost everyone, but in literally thousands of camps and subcamps sprinkled all over the map of Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and France. Wherever slaves could help the Third Reich accomplish its aims, there were camps. Some may have been nothing more than a barn where women workers making hand grenades in a forest armory were locked up at night; others were part of sophisticated underground manufacturing facilities where the first rockets and jet fighters were built and thousands of workers were used up.

Each of the major camps in Germany and Austria—like Dachau, Buchenwald, and Mauthausen, to name three of the oldest and largest—had jurisdiction over a wide geographical area, and each may have had a hundred or more subcamps. Workers were often transferred from one to the other as needed and then transported back to the main camp alive, to be killed, or dead, to be burned.

It’s this system that American soldiers discovered, much to their shock, horror, and surprise, as they chased the German army toward its mythical Alpine redoubt. The GIs had received no warning as to what they might find, but that may not have mattered, for as one of them said to me, “What if we had? How do you prepare to see

that

?”

Most of the more than 150 Americans interviewed for this book were soldiers. Six were U.S. Army nurses. One was a 4F (physically unfit to be drafted) volunteer civilian ambulance driver who worked at Bergen-Belsen with the British and Canadian forces. Three were U.S. Army prisoners of war—two of them Jewish soldiers—who experienced the Holocaust firsthand alongside slave laborers imported from Eastern Europe. Five were concentration camp inmates who developed special relationships with particular GIs and are now American citizens. And one—also an American citizen now—served in the Polish army attached to the Russian army. With them he discovered some of the worst of the camps in Poland but only after all the inmates had been either murdered or evacuated to the west. He finally liberated prisoners in Sachsenhausen and eventually participated in the battle for Berlin.

At the time they were interviewed, the veterans ranged in age from eighty-three to ninety-six. All are among the relative handful of America’s witnesses to the Holocaust who are still alive, still willing and able to recount their experiences, still cognizant of the need to tell their stories.

While researching this book, I discovered that it’s not unusual for veterans not to know, even now, the names of the camps they discovered. Some U.S. medical personnel spent weeks at the camps, but it was more typical for combat troops to spend mere minutes to a few hours inside the gates before moving on in their relentless pursuit of the German army. Although they may not know the names, and though they may have spent but a short time inside their gates, they’ve never forgotten what the camps looked like, how they smelled, how the inmates looked, and how it all made them feel. And that is what this book is about. This is their opportunity, perhaps for a final time, to tell the world what they saw.

Writing about the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1963, Hannah Arendt used the phrase “the banality of evil” to explain that the Holocaust had been executed by ordinary people willing to be convinced that their actions were normal. In interviewing American soldiers who confronted that evil face-to-face, I became aware of a banality of the language they use to describe what they saw. And through my own personal reaction I’ve come to recognize the danger in that for those of us who are anxious to learn from them. The most vivid example: soldier after soldier from camp to camp to camp described “bodies stacked like cordwood,” to the point that it’s very easy for the shock and horror of such a statement to evaporate into meaninglessness. When an individual soldier was confronted by “bodies stacked like cordwood,” he was seeing them that way, in all their brutal horror, through eighteen-or nineteen-, or twenty-year-old eyes, for the first time. Those kids were confronted with premeditated murders and attempted murders on a scale heretofore unimaginable.

A word, now, about the concept of

the liberators

. Aware that the Americans were coming, the SS guards—often with a final orgy of indiscriminate torture and killing—fled. It was left for the GIs to enter the camps, assess the humanitarian needs of the surviving inmates, bring up rear-echelon forces to minister to them, and arrange for the burial of the dead.

While I have observed the pride that members of specific Army units feel at having been officially designated the liberators of a certain camp, the truth is that their greatest achievement was not in cracking open the gates. Their achievement was in doing everything necessary to liberate an entire continent, and it took between three and a half and four million members of the U.S. armed forces (plus those of British, Canadian, French, and other Allied nations) in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) to do that job.