The Lion Seeker (65 page)

Abel smiled.

Outside on the far side of the lawn the maroon trees were already lit by flames that were not flames: burning but unharmed, life frozen in a blaze. Abel knew this miracle would turn to cold and black with astonishing speed; but tomorrow it would be back again.

âCheers, Da, l'chaim.

âL'chaim.

As he lifted his glass, Isaac touched his wrist and said in Jewish, This is your place now Tutte. It belongs to us, the Helgers, like Mame always wanted. Forever.

It's a beautiful place, Abel said.

I know it's not Parktown, said Isaac. Not yet.

Don't speak foolish, said Abel. I couldn't have dreamed better. You've done it.

Isaac seemed to tremble, his voice a rough whisper. âThank you, Da.

From inside came Gloria's call and, faintly, the smell of good roasting spring lamb with gravy and potatoes. The two men had one final look around the sun-gilded garden, over the burning trees, then they touched glasses and drank and turned to go back inside.

An Epilogue

S

HE IMAGINED THE WOMAN

as wizened, tiny, rough-hewn. But her bulk and her eyes were soft. Her apartment was full of growing things. They sat at the window table with dates and coffee, an open pack of Nadiv cigarettes and a plastic lighter. On the woman's side was a file they both kept ignoring. They spoke Hebrew but slanted off into Yiddish, now and then reaching for more haimisher feelings. Of course she cried; the womanâMrs. Sonya Ponnisâdid not. They talked about their children, the times; they were circling the unseeable, what had brought her here on the long train ride from her kibbutz in the south, then a jolting Egged bus up the sloping roads of this bay city squatting on its blunt mountain.

Ten years old, I remember him, the shochet Zalman Moskevitch.

My grandfather. But not me you don't remember.

You and your mother left in what again?

It was three of us, 1924.

I was ten years old. So many children in my mind.

âUni m'vinuh, Rively said. I understand.

I

don't

, said Mrs. Ponnis. But she wasn't talking about any lapses in her memory, Rively felt; she meant it all. So they came to a deep silence and Rively was suddenly afraid to push her words out into it, like a child at the edge of a great cold ocean. She made a small noise, the equivalent of a prodding toe.

What happened to usâyou've heard before. Same old horror story. The only difference is this village was yours. Ours. Your face belonged there, we have the same look. We can sing the same songs, remember the same smells. Same love in our hearts. Broken hearts.

I want to know, said Rively.

To know? It's gone.

But exactly what happened.

Of course, said Mrs. Ponnis. She turned brisk, mashed a cigarette in a saucer. Began to talk about June 1941, more than twenty years ago now, but still fresh as yesterday morning in her mind. How in Kovno the local boys pulled random Jews off the street into the infamous Lietukis Garageâdid Rively know this?âand beat them to death with tire irons; how a crowd formed to clap and cheer, women holding up children for a better view.

Mrs. Ponnis opened the file and slid across some prints of photographs. Rively saw bodies sprawled, pooled blood. A tall blond youth posed with a metal bar, satisfaction in his face. Mrs. Ponnis said someone there started playing an accordion and the crowd sang the national anthem. I'm showing you this so you can see the feeling in the country from the beginning, the fever that boiled in our neighbours for our blood. The German conquest was just an excuse for them, they didn't need orders. To them every Jew was a Communist deserving execution. And long before the special death squad with all of its Lithuanian volunteers and their little arm bands even got to Dusat, our neighbours had already forced us out of our houses, herded us into the barns under the bridge. You remember the bridge?

Rively bit her wrist.

We had to work in the fields for them, like animals. My father got sick. My mother told me run away. There was nowhere to go. I ran into the woods at night. I was lucky. Spoke good Russian. An Orthodox Christian family in a fishing village near us took me in and hid me as one of their own, and that's how I survived.

Rively nodded, waiting for the rest.

Mrs. Ponnis slid another photograph across.

âZeh hoo?

That is the creature, yes. Jäger.

It was a black-and-white of a man in SS uniform, moustache, cropped hair in a side part with shaved sides.

He's been living in Germany all this time, working on a farm. Under his own name. They finally arrested him just a while ago, March 1959 it was. For war crimes. He killed himself before the trial. A coward as well as a murderer of little children, of women and unarmed men.

Rively stared. She said, The man in charge of finishing off the Jews of Dusat.

He had so many happy helpers. You know, his right hand was an officer called Hamann.

No!

Yes.

God, said Rively.

Hamann

: it was an evil name in the Torah, the name of a villain in the book of Esther who had sought to wipe out the Jews of Persia in ancient times, a reviled name the congregation drowned out with jeers when it was read aloud on Purim. She felt a seam of cold flowing through her, opened by this glimpse of a hidden structure beneath all things, webs of mystic connection.

I'm going to show you something you need to be ready for.

That's why I came.

Do you read German?

Enough to understand, from Yiddish.

The Soviets found this in the archives. It's genuine. They held on to it till now for their own reasons. They call it the Jäger Report.

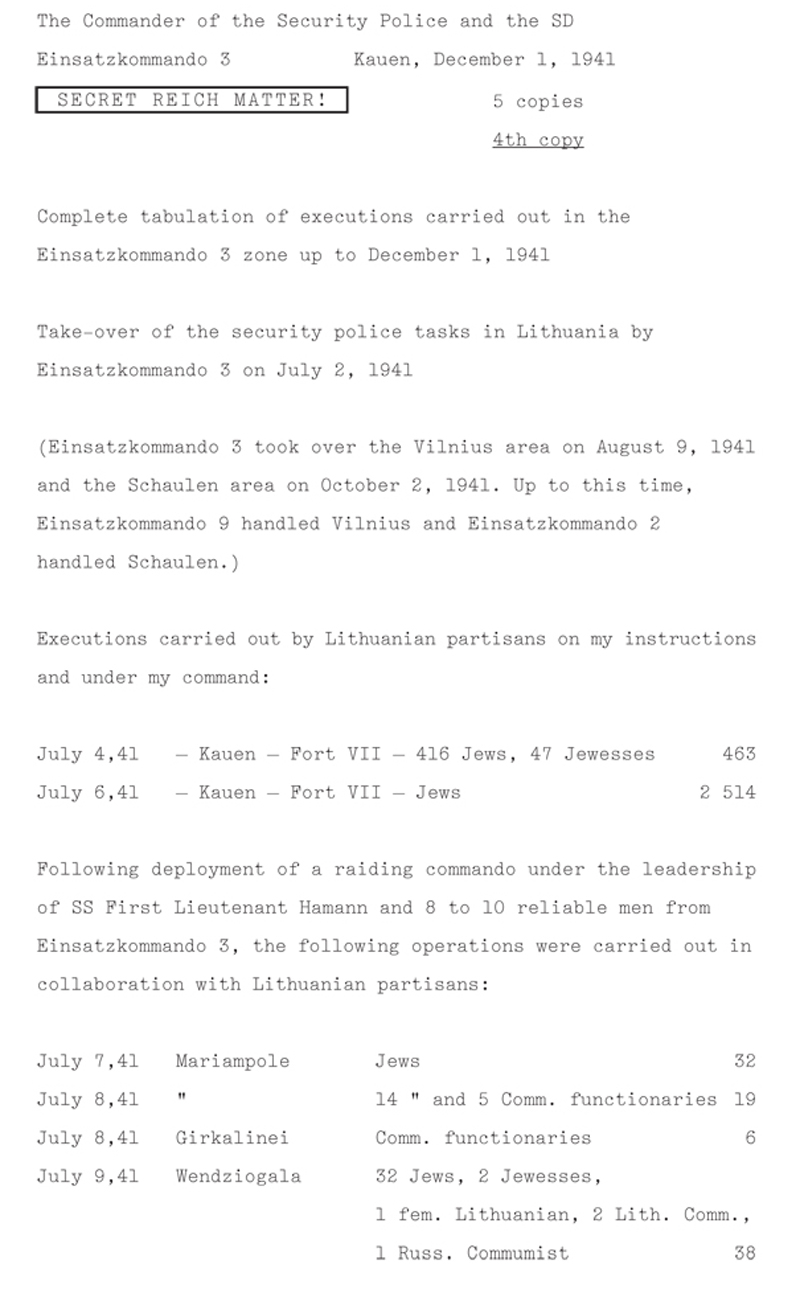

Now Mrs. Ponnis slid across some pages in a neat stack. The top one read:

Â

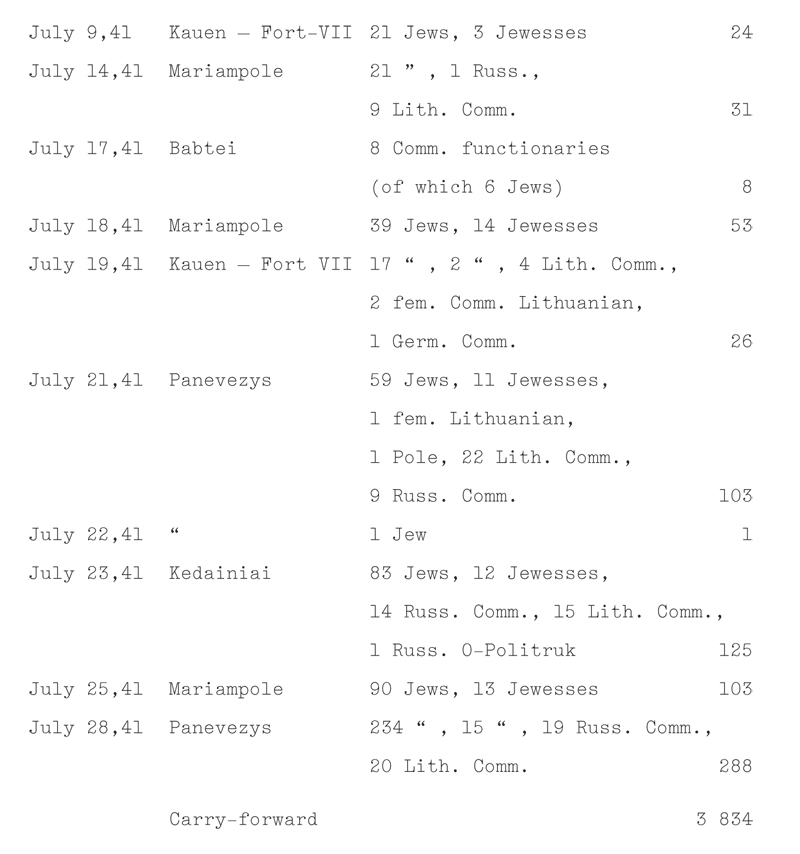

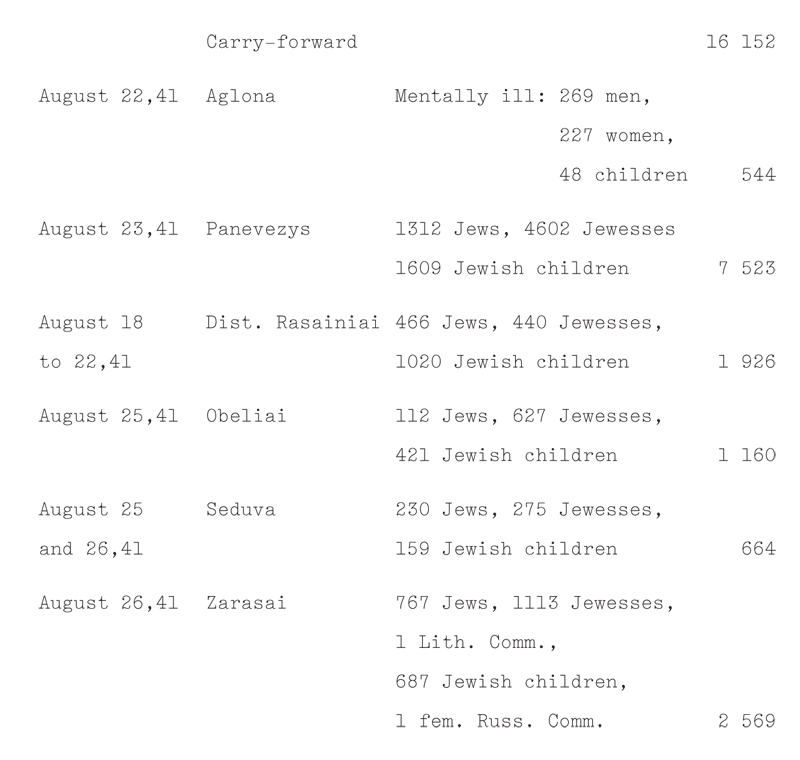

There were another five sheets of this stuff under this first one, the same lists, the ballooning total. Almost all of the victims were categorized as Jews, Jewesses or Jewish Children.

The final total on the sixth page was this: 137, 346.

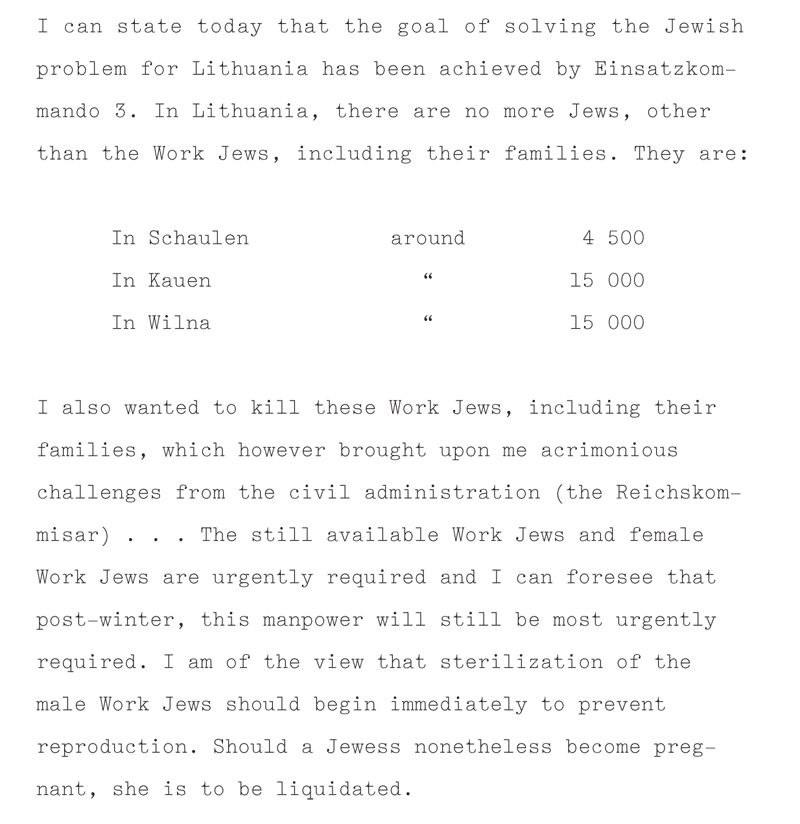

She read it again, sounding the number to herself in carefully separated units. Then came three more pages with conclusions, over the signature of SS Standartenführer Jäger.

After Rively had finished, she began to read it again and then she stopped. Mrs. Ponnis was smoking another cigarette, looking out the window. Rively felt that she, herself, had turned into a different person to the one she was before she'd started reading. The world did not feel as it had before. This was temporary, she hoped.

She said, I don't see Dusat on the list. Dusetos.

Mrs. Ponnis reached over and found the third page, ran her finger down it:

Mrs. Ponnis said: The Dusaters were all included in the Zarasai killing. They marched them miles into the woods of Deguciai, near Saviciunai village. A long deep pit, like a trench, was dug there. They made them strip and stand at the edge of it, and when they shot them they fell in.

Rively was motionless for a minute, staring down at the ink. That very day. Her aunties, their husbands, the children.

It's an important document, said Mrs. Ponnis. In a way, it's where it all started. They killed over a hundred thirty-five thousand human beings in a few weeks, without mercy. Extinguished the Lithuanian Jews. A thousand years of history, more, gone. Vilna was the Jerusalem of the North. Our yeshivas famous for their genius. What

this

showed

them

is that it could be done. That people wanted to help them to do itâthe Lithuanians were doing it even before the Germans took overâand that it was logistically possible. That nobody anywhere else cared, or made much of a fuss about it. It was the first time they started killing children in masses. And women, old people. All the rest of itâthe camps, the gasâfollowed from this, like a fire from a spark.

A sound came out of Rively, the noise of some inner cracking.

Mrs. Ponnis sniffed. This is how it is for us.

Â

At the door she handed the file over. Are you going to show it to your children?

âLoh yoduat, said Rively. I don't know.

You should. All your family should know.

Rively looked down. Not my brother, she softly said.

What?

She shook her head. I have a brother, Isaac. Lives in South Africa.

Yes?

He has a good life there. He's done well, and he looks after our father also.

And so?

She shook her head again. No. I think . . . It's better I let him go on in peace. In happiness. Isaac doesn't need this.

We all need the truth.

Not him.

Mrs. Ponnis watched her. Maybe, she said, maybe you're right. Life is forward. Life is now.

Ai, my God.

What?

You sounded just like her then, Gitelle, rest in peace.

Is that such a surprise?

They hugged and Rively left, walking in a daze till she emerged onto the crest of Mount Carmel. The view scooped away to mineral waters, a Mediterranean horizon of pale blue, waveless under the white kites of swooping birds. She sat on a bench, opened the file across her lap. After a time her eyes closed. Mame, Mame. Memories of Dusat long buried came up as if ploughed from her psyche's deepest soil. One came so vividly it felt alive in her: How when she was sick Mame used to feed her warm milk from their cow Baideluh three times a day. Baideluh lived on straw in the shed behind the house, Baideluh loved them so much. When they sold her to Minsker before they left for South Africa she used to wander back and stand lowing at the window till Mame went out in her nightgown in the pre-dawn mist, to lead her back to the Minsker place near Yoffe's mill, rubbing her side and talking nicely to her as they went.

Softly, Rively began to speak the words of a remembrance prayer, repeating them like a chant.

Give certain rest on the wings of Thy holy presence / Tie the rope of life to the souls of the dead

. The salt wind breathed on her: she paid attention to it but there was no whispering in its motion as her father used to promise her, no murmur from the divine penetrating all things. No: the wind felt only cold, the bench hard. She opened her eyes and looked down at the numbered souls, the erased places. The face of a child was trying to smile, and then soil fell on it. All things have an end and that was her Dusat's, it had happened, the centuries of life had terminated. She would have been there also, in the pit, but for her mother's determination to emigrate. She looked up and Haifa Bay stretched wide its mute jaws of sky and water, a toothless eater of worlds, alive and dead. She had not ceased in the chanting of her words of prayer. To try to sanctify the unholy: you do what you can. Bring light to dark. Lead a Jewish life in a Jewish country. For you, Mame. To be as strong as you were.